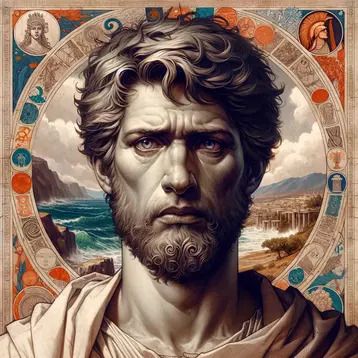

Oedipus

The son of Laius and Jocasta, King and Queen of Thebes, Oedipus is the unfortunate main protagonist of “one of the best-known of all legends” in Ancient Greek – or any other – mythology. Left, while still a baby, to die in the mountains by his father – who had been warned that his son would kill him and marry his wife – Oedipus was eventually adopted by the childless King Polybus and Queen Merope of Corinth. After accidentally finding about the gruesome prophecy himself, in fear and disgust the young Oedipus fled Corinth and – guided by cruel destiny – wound up crossing paths with his real father at a narrow crossroad; after a brief argument with Laius’ charioteer over who had the right to go first, Oedipus killed both of them. Wandering aimlessly, he subsequently reached the city of Thebes where he encountered the monstrous gate-guarding Sphinx; after he answered her riddle, the Sphinx went mad and hurled herself to her death. As a reward for rescuing the city from this vicious beast, Oedipus was afterward offered the vacant throne of Thebes and the hand in marriage of the ex-king’s widow, his very own mother. Jocasta bore her son four children – Polynices, Eteocles, Antigone, and Ismene – before a belated investigation into the death of Laius led Oedipus into discovering the dreadful truth of his marriage. Upon realization, Jocasta hanged herself, and Oedipus gouged his eyes with two pins snatched from her regal dress.

Oedipus, the Abandoned Prince

Oedipus' Biological Parents: Laius and Jocasta

As it often happens in Greek mythology – and, who knows, maybe in life as well – the story of Oedipus starts sometime before his own birth. Laius, the childless King of Thebes, decided to consult the Oracle at Delphi to learn if he and his wife would ever have any children. To his utter dismay, he was told that it would be better for him that they don’t: any son born out of their union was destined to kill him. Laius tried staying away from his wife’s bed as much as he could, but all his effort was undone by a night of revels and sweet-tasting wine. Jocasta got pregnant and, in due time, gave birth to a baby boy. To thwart the prophecy, Laius told his servants to pierce the baby's ankles, so that it would not be able to even crawl, let alone cause him some harm; afterward, so as to be even safer, he gave his son to one of Thebes’ shepherds, telling him to leave the baby in the mountains to die. The shepherd, unable to do such a thing, handed the baby over to a second shepherd, who happened to pasture his flocks on the same mountain.

Oedipus' Adoptive Parents: Polybus and Merope

A Corinthian, this second shepherd took pity on the boy and brought it at the court of King Polybus and Queen Merope of Corinth. The royal couple, also childless, decided to adopt the poor baby and raise him as their own. They named the boy after his ankle wounds: Oedipus means “Swollen Foot.” When Oedipus grew up, he was told by a drunkard that Polybus and Merope were not his birth parents. Deciding to investigate this matter, Oedipus ended up in Delphi, with an intention to learn the truth from the Oracle. Instead of getting the answer he had come from, Oedipus was told that he would kill his father and marry his mother. Upon hearing this, Oedipus decided instantaneously to leave Corinth and go as far from it as possible; so, he headed northward, in the fated direction of his birth town, Thebes.

Killing Laius

On his way there, at a narrow three-way intersection near Daulis, he came across a chariot carrying King Laius, his biological father. Oedipus and Laius' charioteer started quarreling over who had the right of way. The quarrel ended up with Oedipus killing both the charioteer and his father, thus unknowingly fulfilling the first half of his prophecy. Only one of Laius’ servants managed to save his life from the wrath of Oedipus.

The Riddle of the Sphinx

Soon after, Oedipus hit upon the terrible Sphinx, who had plagued the region of Thebes for some time then, destroying crops and devouring travelers who had either refused to answer her riddle or answered it wrongly. The Sphinx asked Oedipus the same question she had asked the unfortunate ones before him: “What walks on four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three at night?” No one had ever answered the question correctly before. But Oedipus thought carefully and eventually solved the riddle: “Man – who crawls on all fours as a baby, then on two legs as an adult, and then with a walking stick when in old age.” The Sphinx, unable to bear the fact that her riddle had been answered correctly, hurled herself off the rock she was sitting on and to her death.

Oedipus the King

King of Thebes

At the time, Thebes had an interim ruler, Creon, the brother of the widowed Jocasta and Oedipus’ uncle. Even before Oedipus’ arrival, Creon had decreed that anyone who would manage to kill the Sphinx would be rewarded the hand of the queen and the throne of Thebes. Consequently – unbeknownst to him or, for that matter, anyone else – Oedipus’ reward for rescuing Thebes from the Sphinx would end up being a most bitter one: his father’s crown and marriage to his mother. Neither recognizing the other, Oedipus and Jocasta begot four children together: Eteocles, Polynices, Antigone, and Ismene.

The Plague

Years later, Thebes is hit with a terrible plague. Oedipus, determined to cure his city, does everything in his power to get to the bottom of the matter; and after Creon returns from a consultation with the Oracle at Delphi with the news that the plague is divine retribution for the killer of Laius never being taken to justice, Oedipus gives a solemn oath to find him and punish him severely – of course, not having even the slightest idea that the killer is, in fact, him. Oedipus questions the prophet Tiresias who, though blind, is able to see more and more profoundly than his questioner. At one point, forced to tell everything he knows, Tiresias points the finger of blame in the direction of the Theban king. However, Oedipus refuses to believe that he could have anything to do with Laius’ murder and instead blames Tiresias for plotting with Creon to depose him.

The Truth

Jocasta tries comforting Oedipus and, in the process, informs him about the events which led to the death of her husband. They sound strikingly similar to his chance encounter with the unknown charioteer at Daulis, and, visibly shaken, Oedipus sends for that one Laius’ servant who managed to survive the scene. However, things go from bad to worse, even before the servant is brought to him: a messenger from Corinth enters the court and informs everyone that Polybus had died. Still believing that Polybus is his real father, Oedipus is somewhat relieved to hear this; however, fearing that the second part of the prophecy may still materialize, he declines to attend the funeral in order to avoid meeting his mother. The messenger informs Oedipus that he doesn’t need to worry about that, for he knows full well that Polybus and Merope aren’t his real parents: it just so happens that he is the very shepherd who handed them the ankle-pierced Oedipus when he was still a baby!

Self-blinding

Jocasta needs no further evidence than this: she flees the scene in utter distress and hangs herself in her chamber. Still unconvinced, Oedipus waits for the single eyewitness of the murder of Laius only to realize that the worst is true: he had, in fact, killed his father years ago and married his mother afterward. Oedipus tries to find Jocasta, and after locating her lifeless body, tears out two golden pins from her gown and pricks his eyes. As he had promised to do with the killer of Laius, he banishes himself from the city; guided by his daughter and sister Antigone, Oedipus reaches the court of King Theseus of Athens, where both are warmly welcomed. Years afterward, after cursing his disobedient sons, the blind and weary-of-life Oedipus is mysteriously taken by the gods at a spot known only to his host Theseus.

The Aftermath

After Oedipus' death, his sons Polynices and Eteocles decide to share the throne of Thebes, but when Eteocles refuses to give the throne once his time is over, Polynices leaves Thebes and returns with an army. The attack of the Seven Against Thebes results in both brothers dying on the battlefield; the conditions of their burial becomes a cause for the famous conflict between Antigone and once-again Theban king, Creon.

Oedipus Sources

Sophocles’ “Oedipus Rex” is widely considered one of the greatest plays ever written – if not the supreme masterpiece of classic Greek drama. Though the second one to be written, it constitutes the first part of Sophocles’ so-called Theban trilogy, as it is chronologically followed by both “Oedipus at Colonus” and “Antigone.” As always, Apollodorus neatly summarizes the full story in his “Library.”

See Also: Laius, Jocasta, Polynices, Eteocles, Antigone, Ismene, Seven Against Thebes, Polybus, Merope, Creon, Sphinx

Oedipus Video

Oedipus Q&A

Link/Cite Oedipus Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Oedipus". GreekMythology.com Website, 28 Aug. 2018, https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Mortals/Oedipus/oedipus.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.