The Trojan Horse

In the tenth year of the Trojan War, despairing at their inability to take the city by storm, the Greeks resorted to a cunning little stratagem. Truth be told, “little” may not be the proper word for it, because the central part of the plan – devised by who else but Odysseus – included the construction of an enormous wooden horse. Almost everybody knows why it had been built and who lay hidden inside the hollow belly of the statue. However, the whole story is a bit more complicated than that; and it includes several memorable episodes you can find out more about below.

The Stratagem

Epeius and the Construction of the Horse

Now, for Odysseus’ plan to work, the Greeks needed a master-engineer; fortunately, they did have one in their ranks: Epeius. True, he had the reputation of being a coward, but as far as architecture was considered, there weren’t many people on the planet who could rival him both in knowledge and vision. He needed no more than three days and just a few helpers to build a huge hollow horse of fir planks, felled on Mount Ida. Following the advice of Odysseus, Epeius also installed a trap-door on one side of the wooden horse, and engraved large letters on the other: “For their return home, the Greeks dedicate this thank-offering to Athena.”

The Heroes in the Horse

Once the Wooden Horse had been built, Odysseus proceeded to persuade the bravest and the most skillful of the Greek warriors present at Troy to climb, fully armed, into its belly. Some say that there were 23 of them, while others speculate with numbers between 30 and 50. Either way, we know for sure that, in addition to Odysseus, Menelaus, Diomedes, Neoptolemus, Acamas, Sthenelus, and Thoas were also there. Even though hesitant and scared stiff, Epeius joined the party as well: he was, after all, the only one who knew how to operate the trap-door.

The Rest of the Plan

Once the night had fallen, the remaining Greeks burned their tents and, led by Agamemnon, sailed off to the nearby island of Tenedos. The plan was to stay there for a night and then go back to Troy. Odysseus’s first cousin, Sinon, was the only one left behind; and for a reason: he was supposed to signal them the appropriate moment for their return.

The Discovery of the Trojan Horse

Priam, Thymoetes, and Capys

At break of day, the Trojan scouts were met with a sight that must have been beyond joyful: the camp of the Greeks lay in ashes, deserted and all but empty. Priam and his sons immediately went out to witness this miracle with their own eyes; and, of course, the only thing they could find there was a giant wooden horse dedicated to Athens. They stood in wonder for some time, before Thymoetes suggested that they should take the horse into Troy and pull it up to Athens’ citadel. Capys, however, had other ideas. “We should hurl into the sea this false Greek gift, or underneath it thrust a kindling flame, or pierce the hollow ambush of its womb with probing spear! Athene favored the Greeks for far too long...” Priam was in favor of Thymoetes’ proposal: since the horse was an offering to a goddess, desecrating it didn’t seem to the king of Troy as such a great idea.

Laocoon’s Warning

At that very moment, hurrying down from the citadel and followed by a large crowd, the Trojan priest Laocoon started shouting from afar: “O unhappy men! What madness this? Who deems our foemen fled? Think ye the gifts of Greece can lack for guile? Have ye not known Ulysses?... This is all a trap. Trust not this horse, o countrymen, whatever it may bring! I fear the Greeks, even when they bring gifts.” Saying that, Laocoon whirled a spear in the direction of the Horse. Numerous cheers followed this fearsome act: “Burn it!” “Pierce it!” “Hurl it over the walls!”

Sinon Clarifies His Presence

This argument was interrupted by the arrival of Sinon, brought in chained by a couple of Trojan soldiers. Now, it is difficult to say whether Odysseus had planned for this part as well, or whether the Greeks merely had a stroke of luck; be that as it may, it was Sinon who eventually convinced the Trojans to roll the horse through the Gates of Troy. He explained to Priam that the Greeks, weary of warring and downcast after the death of Achilles, had deliberated leaving Troy for a couple of months, and they would have done that much earlier if not for the bad weather. Calchas, the most famous Achaean prophet, announced that the only way for the winds to be appeased was through human sacrifice; the scapegoat he pointed his finger at (in a nice touch to the story, supposedly “bribed by Odysseus”) was none other than Sinon himself. However, the favorable winds sprang up before the ceremony took place, and Sinon managed to make his escape in the confusion.

Sinon’s Explanation of the Wooden Horse

“Let’s say that we believe you, Sinon,” replied Priam. “But what’s with the horse?” “Oh, that! It is merely a placatory gift to Athene, who stopped helping the Greeks after Odysseus and Diomedes stole a statue from her temple.” “Nonetheless,” Priam had a good follow-up question, why make it so huge?” But Sinon had an even better answer: “So that you are unable to bring it into the city. For Calchas had prophesized that If you defile it, a horrible ruin – o, may the gods bring it on Calchas rather! – would come on your throne; however, if you manage to wheel it to your own citadel, then you will become a ruler of all Asia and invade Greece.”

The Death of Laocoon

“Lies, all lies,” cried Laocoon. “Every word he uttered sounds as if invented by Odysseus! Believe him not, Priam!” However, it is difficult for one to blame the king of Troy for not taking the Trojan priest seriously when, just as he was saying this, two serpents swam out of the sea and strangled Laocoon and his twin sons. In reality, the snakes were sent by Apollo in punishment for when Laocoon once slept with his wife in front of Apollo’s image; to the eyes of the Trojans, however, they were a sign of the gods: Sinon had obviously spoken the truth, and Laocoon was punished for lying and throwing a spear at the Horse.

The Bloody Celebration

Helen and Deiphobus

With much effort, the Trojans dragged the Wooden Horse inside their Gates, consecrated it to Athene, and started wildly celebrating their victory. During the festivities, Helen and Priam’s son Deiphobos sneaked to the wooden statue. As Deiphobus was observing it in marvel and patting its planks, Helen amused him by calling out the names of the Greek heroes in the voice of their wives. It is not known whether Helen was a part of the plan as well, and this was a whim of overconfidence, or whether she was merely joyful, but, owing to either displeasure or eagerness, many Greeks were tempted to leap out of the horse at this point – especially Menelaus and Diomedes. However, Odysseus restrained them all, patiently waiting for the proper moment for him to enact the final act of his devious plan.

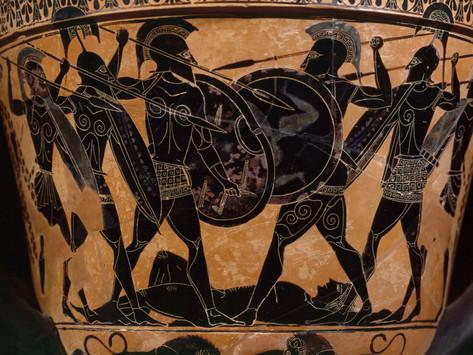

The Attack

At midnight, just before the seventh full moon of that year had risen, Sinon slipped through the Gates of Troy and kindled a beacon – the signal Agamemnon had waited for to return with the Achaean fleet to shore. An hour or so later, in the dead silence of the night, Odysseus raised his sword and ordered Epeius to unlock the trap-door. Echion was the first one to jump out of the horse; being too eager and reckless, he fell and broke his neck; the rest used Epeius’ rope-ladder. Soon enough, Agamemnon’s army stormed through the open gates. Not even the gods could save Troy now.

The Trojan Horse Sources

Most of this story is told by Virgil in the second book of the Aeneid, which you can read here in Dryden’s rhymed version, and here in Theodore C. Williams blank verse translation; for a summary of the same events, consult the epitome of Apollodorus’ Library.

See Also: Trojan War, The Sack of Troy, The Returns of the Greek Heroes, Odysseus

The Trojan Horse Video

The Trojan Horse Associations

Link/Cite The Trojan Horse Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "The Trojan Horse". GreekMythology.com Website, 13 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/The_Myths/The_Trojan_Horse/the_trojan_horse.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.