The Returns of the Greek Heroes

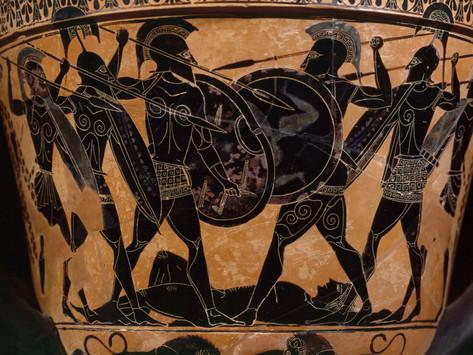

The Trojan War lasted for ten years and claimed the lives of many heroes, both Greek and Trojan. An even-sided affair, in the end, the conflict was decided through a combination of ingenuity and a stroke of luck. Instead of believing their own priest, Laocoon, the Trojans chose to accept as true the testimony of a Greek traitor named Sinon, and this resulted in them mistaking Odysseus’ shrewd stratagem, the Trojan Horse, for a divine gift. The Trojans spent the night celebrating and reveling, but most of them didn’t live long enough to see the morning: at midnight, the strongest of the Greek heroes suddenly climbed out of the belly of the Horse and attacked their disordered and inebriated enemies. During the sack of Troy, the Greeks killed every member of the Trojan royal family and took with them almost every Trojan princess. However, very few of them managed to return to Greece; most of those who did met their ends in ways unfitting for legendary warriors.

The Mighty Five

Menelaus

Menelaus and Agamemnon – the revered sons of Atreus, and, in more ways than one, the initiators of the Trojan War – couldn’t agree on when to set sail for Greece. Menelaus wanted straight away, but Agamemnon insisted on sacrificing something to Athena first. The brothers failed to reach an agreement and separated on bad terms; they would never see each other again. Menelaus’ was the one who embarked on the journey first, but he reached Sparta much later than Agamemnon—by that time, already killed by his wife. First, Menelaus’ fleet was blown by strong winds (sent by the vengeful Athena) to Crete and then to Egypt. There Menelaus and his few remaining companions spent the next eight years, windbound and unable to return home. Advised by the nymph Eidothea, Menelaus eventually captured the shapeshifting sea-god Proteus, who informed him both of the death of his brother and of the sacrifices he is entitled to make to be granted favorable winds from the gods. Accompanied by his wife Helen, Menelaus reached Sparta on the very day that Orestes killed Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. The two lived a quiet and happy life and, on their death, the lovers were supposedly both made immortal by Zeus.

Agamemnon

Compared to that of his brother Menelaus, Agamemnon—joined by the Trojan princess Cassandra and probably guarded by Athena—enjoyed a prosperous journey back home. However, he didn’t know that, in his absence, his wife Clytemnestra (angry at him for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia) had taken his cousin Aegisthus as her lover; neither could he have guessed that the day of his arrival would be the last day of his earthly existence; in actual fact, his murder had been prepared long before he came ashore and kissed the Greek land with otherworldly joy. Eight years would pass before Agamemnon’s death is avenged by his son Orestes, an event which will put an end to the cycle of death and revenge for more than this family.

Odysseus

It would take us much more than a single paragraph to list even a tenth of the things that Odysseus had to live through before finally arriving in Ithaca. For the purposes of this article, it’s safe to say that not only he needed a decade to reach his home, but he also had to deal with the suitors of his wife Penelope once he reached there. It is difficult to say what happened next since different authors tell different stories of Odysseus and Penelope’s later years, ranging from a murder motivated by infidelity to a “happily ever after” marriage. Either way, there should be no doubt that Odysseus’ glory years were those between the fall of Troy and his arrival in Ithaca; whether in peace or infamy, he spent the rest of his life far from the eyes and ears of poets.

Diomedes

Diomedes, the son of Tydeus and Odysseus’ most faithful companion, was one of the few Greek heroes who safely reached their homeland. However, back in Argos, he found out that his wife Aegialeia had become the mistress of Cometes, Sthenelus’ son. Some say that she was tricked into cheating Diomedes by Nauplius, the father of Palamedes, whom Diomedes and Odysseus had treacherously killed sometime before; however, it is far more probable that he was just being punished by Aphrodite, for having wounded the goddess at Troy. Either way, Diomedes left Argos for Italy, where he settled in Daunia, marrying the daughter of King Daunus, Euippe, and founding quite a few famous cities. It is said that in his later years, Diomedes was visited by Turnus, the prince of the Rutulians, who came to seek his help against an old enemy of his, Aeneas. “I’m done offending Aeneas’ mother,” replied Diomedes, referring, of course, to Aphrodite, and having learned his lesson the hard way. Diomedes met his end at the hands of Daunus, most probably jealous of the fame his son-in-law had acquired in the meantime. It is entirely possible, however, that he was made immortal afterward or, at least, that his followers were miraculously transformed into birds to lament his death for all time.

Neoptolemus

Neoptolemus, the ruthless of all Greek soldiers during the sack of Troy, sailed homeward just as soon as he had offered sacrifices to the gods and his father’s ghost (Polyxena). He took, as his war-spoils, the Trojan seer Helenus and Hector’s widow, Andromache. Helenus, in gratitude for having spared his life, instructed Neoptolemus to avoid the Cape Kafireas promontory; Neoptolemus heeded to Helenus’ advice, and, thus, managed to avoid the great storm which destroyed most of the Greek fleet and took the lives of many Greek heroes. Now, it was Neoptolemus who felt as if he owed something to Helenus; so, he promised him the hand of Andromache sometime in the future. Then again, Neoptolemus might have had another reason to do this, for, during the war, Menelaus had pledged to give him Hermione, his daughter with Helen, and Neoptolemus certainly planned to wed her as soon as she reached her marrying age. However, unaware of Menelaus’ pledge, Hermione’s grandfather Tyndareus had also promised her to Orestes in the meantime. There are contradictory accounts as to what happened next. However, all of them end at Delphi with Neoptolemus being killed because of some sacrilege. It seems that, despite Tyndareus’ promise, Menelaus decided to send Hermione to Phthia; however, she turned out to be barren, which is why Neoptolemus went to search for advice at Delphi; there, he either didn’t sacrifice properly or casually offended Apollo for having killed his father. It is also possible that he happened upon Orestes who either killed Neoptolemus himself or instigated the Delphians to do so blaming him for one of the blasphemies above. Be that as it may, he never returned to Phthia, and both of his wives remarried: Andromache to Helenus, and Hermione to Orestes.

The Rest of the Heroes

Many of the Greek heroes who sacked Troy never reached Greece again, dying in a great storm sent by Poseidon at Cape Kafireas; of those who did, few more bear at least a passing mention.

Calchas

It was predicted that Calchas, the seer who accompanied the Greeks to the Trojan War, would die only if he met a prophet more farseeing than him. That happened very soon after the end of the war, in Colophon, a city near Troy. There, Calchas happened upon Mopsus, son of the prophetess Manto, the only daughter of the Theban seer Teiresias from the period he had been a woman. Mopsus dared Calchas to a duel, which the latter pridefully accepted, challenging Mopsus to say the exact number of figs borne by a nearby wild fig-tree covered with fruit. Mopsus gave the right answer, and, in turn, challenged Calchas to guess the number of piglets an adjacent pregnant sow would give birth to. Calchas said eight, but Mopsus predicted better, guessing not only the right number (either three or nine), but also the exact time of birth and the gender of all piglets. Humiliated and heartbroken, Calchas died on the spot.

Demophon

At Thrace, Demophon fell in love with the Bisaltian princess Phyllis and married her; however, he got tired after a while and decided to go home to Athens. Assuming that he had no intention of coming back, Phyllis gave him a casket and told him to open it only if it ever happens that he abandons all hope of returning to Thrace. Probably out of curiosity, Demophon did open the casket after some time; nobody knows what was inside it, but whatever it was, it sent Demophon in a mad frenzy; he died a lunatic, falling down on his own sword.

Teucer

The great archer Teucer successfully returned home to Salamis, but, as he had predicted, it wasn’t a warm welcome by any means. His father Telamon, angry for not bringing with him the body of his dead half-brother Ajax on his arms, quickly disowned and banished him. Either because he managed to conquer the island with the help of King Belus of Syria, or because he married the daughter of king Cyniras, Teucer eventually settled in Cyrus, where he founded a new city. He named it Salamis, after his home city-state.

Philoctetes

Philoctetes too reached his hometown of Meliboea in Thessaly, but, much like his fellow-archer Teucer and Diomedes, he was expelled from there—in his case, by rebels. He fled to Southern Italy where he founded at least two cities. After his death, he was buried in their vicinity, beside the river Sybaris (Coscille).

Nestor

It seems that only Nestor, the most just and most pious of all Greek heroes under Troy, was blessed with a peaceful and safe journey to his hometown of Pylus. He spent the rest of his life there, undisturbed by wars, joyous and serene, and surrounded by wise and courageous sons and grandsons. He died a revered sage, into extreme old age, having ruled through three generations of men.

The Returns of the Greek Heroes Sources

One of the so-called Trojan Epic Cycle, The Nostoi (or The Returns of the Greeks) is a lost epic which supposedly retold many of the stories summarized above. You can read a few fragments of it here, and a brief summary by Proclus, an ancient philosopher, here. Speaking of summaries – don’t forget to consult the relevant sections of the Epitome of Apollodorus’ Library!

See Also: Trojan War, The Trojan Horse, The Sack of Troy, Odysseus

The Returns of the Greek Heroes Video

The Returns of the Greek Heroes Associations

Link/Cite The Returns of the Greek Heroes Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "The Returns of the Greek Heroes". GreekMythology.com Website, 06 Oct. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/The_Myths/The_Returns_of_the_Greek_Heroes/the_returns_of_the_greek_heroes.html. Accessed 19 April 2024.