Antigone

Antigone by Sophocles

One of Sophocles’ earliest surviving plays, Antigone is often thought of a perfect specimen of Ancient Greek tragedy. It begins a day after the defeat of the Seven against Thebes, soon after Creon, the new ruler of the city, has announced that Eteocles, who has died defending the city, shall be buried with honors, but his brother, the traitor Polynices, shall be left for the dogs to devour. In the prologue of the play, Antigone tries in vain to persuade her sister Ismene to defy the decree, eventually leaving to bury Polynices by herself. A while later, a guard tasked with watching over the body, informs Creon that someone has secretly performed burial rites. Creon threatens him with death lest he finds the perpetrator and, later on, he does: it is, of course, Antigone, Creon’s niece. She refuses to apologize, claiming that it was always her divine right to bury a dead brother, and Creon’s edict was nothing more but a state document. Creon imprisons Antigone, and his heart isn’t softened even by Haimon, his son, who is also Antigone’s fiancé. On the contrary: just after the end of his discussion with Haimon, Creon sentences Antigone to be walled up alive in a cave. As she is taken away there by a guard, the blind prophet Teiresias informs Creon that he has offended the gods by allowing the birds and the dogs to infest their temples with the meat from the unburied Polynices. Creon departs to bury him and to release his niece, but arrives at the cave a bit too late, only to find Antigone already hanged and embraced bt Haimon, who subsequently kills himself. Upon hearing the news, Creon’s wife, Eurydice, hangs herself as well. Creon, nothing but a shade of a man now, dubs himself “twice dead” and, while blaming himself for the deaths of all of his beloved, asks his servants to lead him away.

Date and Historical Background

Although a case can be made for 438 BC, Antigone is generally believed to have been written and performed in or a little before 441 BC, making it the earliest one of Sophocles’ three Theban plays (which include Oedipus Rex and Oedipus at Colonus), though the events it depicts place it last in the chronological order. As many of Sophocles’ productions, it was received with overwhelming enthusiasm, and the trilogy it was originally part of (we don’t know much about it) won first prize at the Dionysia festival.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Antigone, daughter of Oedipus

• Ismene, daughter of Oedipus, sister of Antigone

• Creon, king of Thebes

• Eurydice, Creon’s wife

• Haemon: son of Creon and Euridice, Antigone’s husband-to-be

• Teiresias, a blind prophet, guided by a Boy

• The Guard, a Theban soldier serving Creon

• Messengers

• Chorus of Theban Elders

Setting

In front of the royal palace in Thebes.

Summary of Antigone

Prologue

As depicted in Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes, on the day before the one during which the entire action of Antigone takes places, Eteocles and Polynices—Oedipus’ two sons—slay each other in a single fight. Their uncle Creon, the new ruler of Thebes, decrees that Eteocles, who has died defending the city, shall be buried with full honors, while Polynices, the traitor who had gathered the Argive army to conquer Thebes, is to be left for the dogs to devour.

In the “Prologue” of the play, Antigone, resolved to defy this edict, tries to persuade her sister Ismene to join her in the deed; Ismene, instead, vainly attempts to dissuade her. Finally, after a brief discussion, Antigone leaves to bury her brother Polynices alone.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The Chorus, comprised of fifteen Theban elders, enters the stage. They inform the audience that Creon has summoned them to meet him. While they wait for him, in a celebratory ode, they remind us of the events that have taken place during the previous few days, describing the danger from which the city has been saved and expressing their joy at the famous victory.

First Episode

Creon comes forth and acquaints the Theban elders with the nature and the reasons behind his decree: though both of them princes, Eteocles and Polynices must be treated as differently as one would a patriot and a traitor. The Chorus hesitantly agrees.

Just at that moment, a guard (one of the men tasked with watching over Polynices’ body) arrives before Creon and announces that an unknown person has somehow already paid burial rites to Polynices by sprinkling dust on his corpse. Enraged, Creon threatens the guard: “If you do not find the very hand that made this burial, and reveal him before my eyes, mere death shall not suffice for you.”

The choral ode which follows (the first stasimon)—often printed separately from the play as “The Ode to Man”—is one of the most admired lyric songs of the ancient world. Incited by the mysterious burial rite announced by the guard, the Theban elders celebrate man’s inventiveness and achievements, famously claiming that “wonders are many, and none is more wonderful than man.”

Second Episode

As the Guard comes back leading in a young girl, the leader of the Chorus suddenly interrupts the ode: “I am bewildered!” he exclaims. “I know her. How can I deny that this girl is Antigone? O unhappy child of your unhappy father, of Oedipus! What can this mean? What! Surely they are not bringing you captive for disobeying the King's laws and being caught in lunacy?”

Unfortunately, as the audience already knows, that is precisely what it means: even though aware of the edict, Antigone has decided to pay funeral rites to her brother believing that no human law can ever supersede the higher law of the gods and the ancestral, familial bonds. “It is not my nature to join in hate,” she says, “but in love.”

Enraged by this act of defiance, Creon threatens Antigone with a death penalty and calls immediately for her sister to be brought before him, suspecting that Ismene might have taken part in the deed as well. “I performed the deed,” Ismene says almost immediately upon seeing Antigone, “and I share and carry the burden of guilt.” Her sister rejects this claim outright: “Do not share my death. Do not claim deeds to which you did not put your hand. My death will suffice.” However, Creon—who refuses to be moved even by the fact that Antigone is betrothed to his son, Haemon—takes it into consideration: he now orders that both sisters shall be taken into the palace and closely guarded until their sentence is determined.

In the second stasimon, the Chorus sings of the curse of the Theban royal line, lamenting the fact that the last “dazzling ray of hope spread over the last roots in the House of Oedipus” (Antigone and Ismene) must soon be darkened by everlasting death.

Third Episode

Haemon enters to plead for the life of his fiancée. His words don’t touch Creon, neither when spoken from the position of a son, nor when carefully articulated from the position of a fateful subject concerned for the authority and reputation of a just king. Strangely enough, it seems that they do even more damage when spoken from the position of a caring and passionate lover.

“Bring out that hated thing,” Creon angrily interrupts his discussion with Haemon. “May she die right now in her bridegroom's presence and at his side!” “No, not at my side will she die,” Haemon replies. “Nor shall you ever look at me and set eyes on my face again.” As Creon is to discover very soon, this is not merely just another rambling of a spoiled teenager—but a suicide note. After Haemon leaves, Creon announces to the Chorus that he has decided to spare Ismene, whom she now believes to be entirely innocent, and to confine Antigone in a sepulchral chamber and leave her there to die out of hunger.

In the fourth choral ode (the third stasimon), the Theban elders celebrate the power of love, whom no mortal man or god can ever escape.

Fourth Episode

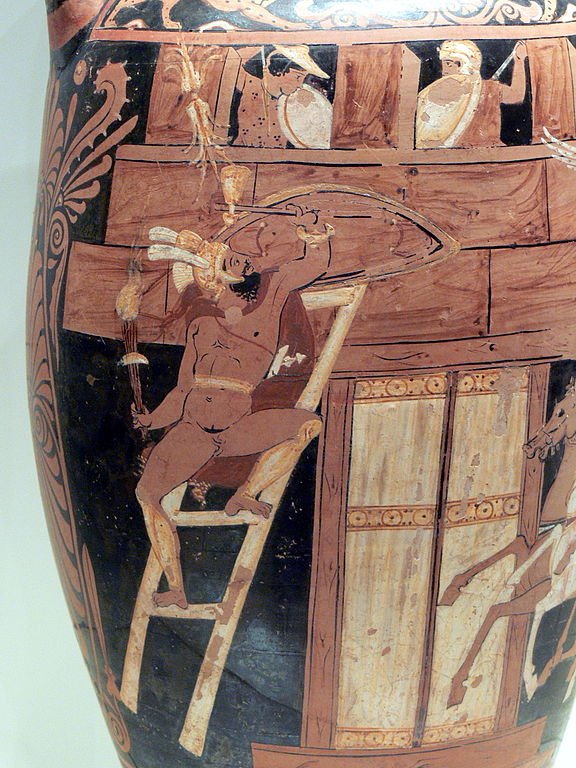

Antigone is now brought out from the palace by two guards tasked with conducting her to her living tomb. The very sight of her touches the Theban elders, who, nevertheless, note that she has only herself to blame for her fate: “Your pious action shows a certain reverence,” they say to her, “but an offense against power can in no way be tolerated by him who has power in his keeping. Your self-willed disposition is what has destroyed you.”

Bemoaning her fate to innocent enter her unfortunate bridal-chamber, the tomb, Antigone expresses her confidence that much love must await her beyond the grave, on the other side. Then she enters the tomb to be seen no more.

In the fourth stasimon, the Theban elders sing of three other mythological figures supposed to have suffered Antigone’s fate, i.e., cruel imprisonment: Danae, Lycurgus, and Cleopatra.

Fifth Episode

The blind and aged prophet, Teiresias, enters the stage, led in by boy.

He comes with an urgent proclamation for the king: the altars of Thebes and its hearths have all been tainted by the birds and dogs with the carrion taken from Polynices, “the sadly fallen son of Oedipus,” and so the gods refuse to accept his prayers and sacrifices anymore.

Creon, however, refuses to believe Tiresias and, instead, accuses him of complicity in some kind of a plot designed to undermine his authority. Say what you want, the king adds, but Polynices will remain unburied, “even if the eagles of Zeus wish to snatch and carry him to be devoured at the god's throne.”

Tiresias, angered, declares that as a punishment for Creon’s confusing of the worlds of the living and the dead (Polynices, though dead, lies unburied, and Antigone, though alive, is entombed), Haemon, his only son will have to die.

Creon, suddenly moved and distressed, resolves to yield. After a brief consultation with the Theban elders, he heads to bury Polynices and release Antigone from her prison. Gladdened by Creon’s decision, the Theban elders burst into a joyous ode calling upon Dionysius to visit the avenues of Thebes and purify the city of its “violent plague.”

Exodos (Exit Song)

Soon after Creon’s departure, a Messenger comes back to announce some unfortunate news. Upon overhearing this, Creon’s wife, Eurydice, faints inside the palace and, after recovering consciousness, comes out of it and demands the whole story.

It is a dreadful one. We learn that after properly burying Polynices, Creon and his servants opened the tomb of Antigone only to find the girl there hanging by her bridal veil, with Haemon embracing her dead body. On seeing his father, Haemon, in a frenzied state, attacked him and, after Creon’s escape, killed himself.

Having heard the news, Eurydice retires into the palace at about the same moment when Creon comes back, carrying Haemon’s covered corpse upon a bier. As he laments his destiny, another Messenger rushes out from the palace, announcing to him that his wife, Eurydice, has stabbed herself, her last words nothing more than a few curses directed at him.

“I killed them both,” cries out Creon, “and never will I be able to blame someone else for their demise!” Dubbing himself “no more than a dead man,” Creon asks his servants to lead him away. As he is conducted to the palace, the leader of the Chorus speaks the closing words of the play: “Wisdom is the chief part of happiness, and our dealings with the gods must be in no way unholy. The great words of arrogant men have to make repayment with great blows, and in old age teach wisdom.”

A Brief Analysis

Widely considered one of the greatest of all Ancient Greek tragedies, Antigone raises a number of challenging and thought-provoking questions, the answers of which, over time, seem to have evolved in favor of the tragic grandeur and beauty of the eponymous character.

Creon, the Just Ruler

Originally, it is difficult to imagine anything even remotely similar: to the all-male Greek audience of fifth-century Athens, Antigone was probably nothing more but a dangerous woman meddling in the manly affairs of the state, and Creon was the tragic hero of the play who, just like most tragic heroes in Sophocles, actively collaborates in his own ruin.

A close reading of Antigone reveals that, indeed, neither the Chorus nor Teiresias ever considers Antigone’s act just, both of them criticizing Creon only after they learn that the gods are offended by its consequences. The final words of the Chorus—where the moral of Ancient Greek plays is usually made known—concerns the life of Creon and not that of Antigone. Moreover, the fact that Creon was undoubtedly played by the protagonist (the first actor) and Antigone by the deuteragonist (the second actor) serves as further evidence that Sophocles might have imagined the central tragedy of the play to be the one revolving around Creon’s arrogance and fanaticism.

The tragedy, put simply, is not that Creon is wrong in his decision to leave Polynices unburied and put the interests of the state before those of the individual (Antigone). The tragedy is that he persists in this decision so much that eventually (most evidently, during the discussion with Teiresias) he starts defending it only because he has put his own interests before those of the state.

Creon vs. Antigone: The Perfect Conflict

In the 19th century, however, German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel proposed a different and very influential interpretation of the play. Dubbing Antigone “the perfect play,” he claimed that the tragedy dramatizes the unresolvable conflict between two equally valid and mutually exclusive “rights”: the right of the state and the right of the family (Hegel refers to them as claims of law and of conscience).

In other words, for Hegel, both Creon and Antigone are tragic characters, but not because (as Aristotle would say) they are neither entirely good, nor wholly bad, but because both are persistent in their views and fail to see that it is their ethical one-sidedness which is bound to result in some kindof tragedy.

In this case, the play isn’t at all about who’s right and who’s wrong, but about the reconciliation of two extreme embodiments of two particular rights, Creon and Antigone, who, precisely because of their “extreme goodness,” are not compatible with the complex nature of the real world.

Antigone, the Martyr

Nowadays, though, after a century torn apart by totalitarian governments, it is impossible to think of Creon as merely a proud, but just ruler, and of Antigone as yet another troublemaker. On the contrary: even against some of the words written in the play, we are more inclined to see Creon as an unreasonable tyrant and Antigone as a rebellious and highly sympathetic martyr.

Consequently, for modern readers, the real tragedy is not the terrible fall of Creon from grace, but the death of the innocent Antigone, and the play isn’t about arrogance being adequately punished, but about the inevitable fate of the rulers who sacrifice the rights of the individuals for the interests of the greater good.

Antigone Sources

There are many translations of Antigone available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read Richard Claverhouse Jebb’s translation for Cambridge University Press here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Edward Hayes Plumptre’s blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Sophocles, Antigone, Seven Against Thebes, Creon

Antigone Video

Antigone Associations

Link/Cite Antigone Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Antigone". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Sophocles/Antigone/antigone.html. Accessed 19 April 2024.