Seven Against Thebes

Seven Against Thebes by Aeschylus

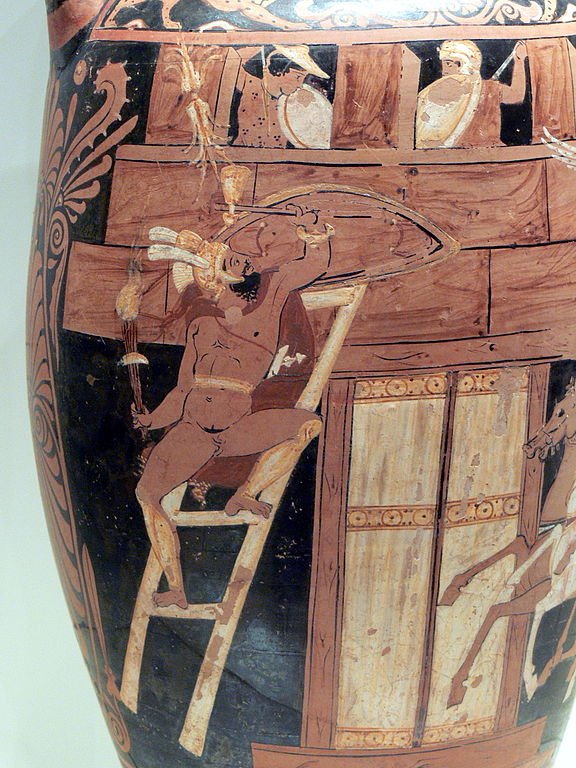

The third play in a Theban trilogy dealing with the devastating effects of the curse of Oedipus, Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes was first performed in 467 BC at the City Dionysia where it won the first prize for tragedy. Featuring little to no action, the play mainly consists of dialogues between Eteocles, a Theban scout reporting from outside Thebes, and a Chorus of fearful Theban girls, regarding the ongoing attack of an Argive army led by Eteocles’ brother, Polynices. Both brothers claim right to the throne of Thebes, but, since Eteocles has refused to share it with Polynices, the latter decided to summon an army and attack Thebes. Eteocles gathers from the Scout that his brother’s intention is to send his seven bravest commandeers at each one of the city’s seven gates, and, once he learns their identities, he chooses a suitable defender for each Argive attacker. Since the final gate’s attacker is none other than Polynices, Eteocles unflinchingly pairs himself up with him, which – as a prophecy has once suggested – inevitably leads to the death of both brothers. At the end of the play, Thebes is saved, but kingless: the ancient curse has finally wiped out Laius’ regal line.

Date and Historical Background

First performed in 467 BC, Seven Against Thebes was the third play in a trilogy which included Laius and Oedipus; both of these plays, in addition to the accompanying satyr play Sphinx, are now no longer extant.

Sometimes referred to as Oedipodea or Aeschylus’ Theban production, the trilogy won the first prize for tragedy at the City Dionysia.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Eteocles, the king of Thebes, son of the dead Oedipus

• Theban Scout

• Chorus of Theban girls

• Antigone

• Ismene

• Herald

Setting

The play is set inside Thebes, most probably at the royal palace.

Summary of Seven Against Thebes

Prologue

From a discussion between Eteocles and a Scout, we learn that Thebes is under siege: led by Eteocles’ brother Polynices, the Argive army is preparing to send seven of its fiercest fighters at each one of the city’s legendary seven gates.

It is not explicitly stated in the play, but we know from other sources the events which resulted in such an outcome.

Namely, even though Eteocles and Polynices were supposed to divide the kingship of Thebes between them (switching annually), Eteocles refused to surrender his crown at the end of the first year, so Polynices asked the Argives to help him recover his share of the throne.

So now, war is inevitable.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

As Eteocles leaves, furiously determined to defend his city to his dying breath – “May they never hold the free land and city of Cadmus beneath the yoke of slavery!” – a chorus of Theban girls enters the stage in fearful agitation.

“In terror we wail loud cries of sorrow,” they sing, already seeing in their mind’s eye the clash of shields and the rattle of chariots; they end their entrance song with a prayer, begging almost each one of the Olympian gods to save Thebes or, even better, “to drive away the onrushing evil” altogether.

First Episode

“You intolerable creatures!” shouts Eteocles angrily upon hearing the cries of the fearful Theban maidens. “I ask you, is this the best way to save the city?” He follows this rhetorical question with a particularly misogynistic statement:

“May I never share my home with a woman, neither in times of evil nor in precious prosperity: when things go well for her, she’s unbearable in her audacity, and when she is afraid, she is an even greater trouble for both her house and the city.”

Eteocles blames the Theban girls for causing unnecessary panic among the citizens of Thebes, rattling them into dispirited cowardice at the worst possible moment.

“Be silent, wretched women,” he orders them after a brief back-and-forth discussion (called stichomythia), adding that if they should pray, they should do it through a stronger and manlier prayer, one which embraces destiny full-heartedly while soliciting the gods to fight on their side.

The Theban girls agree, but, once Eteocles leaves, in their second choral song (the first stasimon), they express their fears yet again, this time even more helplessly. “We heed him,” they sing, “but our hearts are sleepless with terror and anxieties are its neighbors.”

Second Episode

Though rather static – it is nothing but a lengthy discussion between Eteocles and the Theban Scout, interspersed with a few prayers by the Theban maidens – the second episode is the central of the play, and is famously known as the Shield Scene.

In it, the Theban Scout announces to Eteocles each of the seven Argive leaders assigned by lot to the seven gates of Thebes, describing in full their arms and interpreting their shields’ symbolism, so that Eteocles may ascribe a suitable defender afterward.

This is the final arrangement:

|

Gate |

Attacker |

Defender |

Symbol / Omen |

|

Gates of Proetus |

Night |

||

|

Electran Gates |

Fire |

||

|

Neistid Gates |

Tower |

||

|

Gates of Athena Onca |

Hyperbius |

||

|

Borraean Gates |

|||

|

Homoloid Gates |

Lasthenes |

/ |

|

|

The tomb of Amphion |

Polynices |

Eteocles |

Justice |

Upon pairing himself up with his brother, Eteocles is confronted by the pious Theban girls. “No, dearest of men, son of Oedipus, don’t go,” they beg him. “This all-Greek bloodshed is sinful in itself, but when men of the same blood kill each other, the pollution never grows old.”

Eteocles is adamant in his resolution, but as soon as he leaves, in their third choral song (the second stasimon), the Theban maidens uncover the reason for their anxiety. Eteocles and Polynices are destined to become the last victims of a family curse which has already claimed the lives or the sanity of quite a few members of their household over three generations.

Third Episode

In the third episode, the Scout returns to the palace of Thebes to report that the city is saved, but that, unfortunately, it is now kingless: Oedipus’ sons have indeed killed each other, thus wiping out Laius’ royal family line.

In the fifth choral song of the play (the fourth stasimon), the Theban girls express their disquiet and bittersweet feelings upon hearing this news: “should we rejoice and shout in triumph for the unharmed safety of the city,” they sing, “or should we lament our leaders in war, now wretched, ill-fated and childless?”

Exodos (Exit Song)

As Eteocles’ and Polynices’ bodies are brought back to the palace, the Theban girls acknowledge that this is a time to weep and to mourn, and they burst into a protracted grieving song for the brothers’ unkind fate; they divide into two groups, each one cursing the fate of one brother.

It is believed that this is how originally the play (and the trilogy) must have ended; however, perhaps due to the popularity of Sophocles’ Antigone, at least a hundred verses were added to it in the fourth century BC.

In them, Antigone and Ismene, Eteocles and Polynices’ sisters, appear on the stage, and a Theban herald forbids the burial of Polynices as a traitor. Antigone announces her intention to bury him nevertheless – a vow which sets the stage for Sophocles’ eponymous play.

A Brief Analysis

Just like in Oresteia, Aeschylus is dealing with the devastating effects of a family curse in the Oedipodea as well; however, unlike Eumenides, the final part of this trilogy, Seven Against Thebes, offers no redemptive resolution.

However, even though we don’t have Laius and Oedipus to either confirm or deny this, it seems that Oedipodea was also a trilogy about an impious crime and a fitting punishment. Namely, in the second stasimon, the Theban girls inform us that Eteocles and Polynices’ grandfather, Laius, acted consciously in defiance of Apollo “who, at his Pythian oracle at the earth's center, said three times that the king would save his city if he died without offspring.”

For some reason – the play is lost, so we can only guess, but Apollodorus blames it on the wine – Laius didn’t abide by this conditional prophecy, so the gods punished him over three generations until his family line was wholly eradicated.

As is typical for Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes features a larger-than-life protagonist: to the background of a stereotypically fearful female chorus, Eteocles is portrayed not merely as a cursed son, but also as a more than worthy leader, who brings about his end both knowingly and stoically for the future benefit of his people.

Seven Against Thebes Sources

There are many translations of Seven Against Thebes available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read Herbert Weir Smyth’s translation for the Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Edwyn Bevan’s blank-verse adaptation here.

See Also: Oresteia, Persians, Suppliants, Prometheus Bound

Seven Against Thebes Video

Seven Against Thebes Associations

Link/Cite Seven Against Thebes Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Seven Against Thebes". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aeschylus/Seven_Against_Thebes/seven_against_thebes.html. Accessed 27 April 2024.