Agamemnon

Agamemnon by Aeschylus

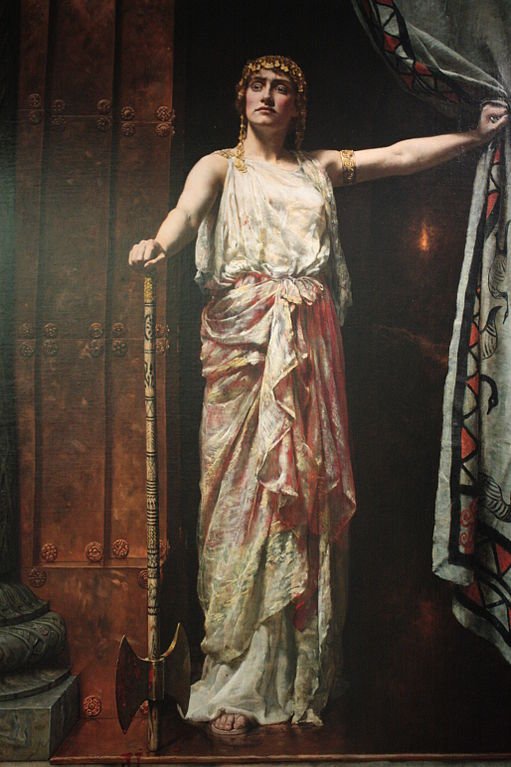

Originally performed in 458 BC, Agamemnon is the first play in Aeschylus' Oresteia trilogy, which also includes Libation Bearers and Eumenides. The play is set in front of the palace of Argos and begins with a Watcher noticing a beacon fire which signals the return of Argos’ king, Agamemnon, ten years after sailing away to conquer Troy. The information is subsequently confirmed by a Herald, soon after which Agamemnon arrives in a chariot that also carries Cassandra, the Trojan princess, a spoil of war and a new bedmate of Agamemnon. Regardless of this, Clytemnestra welcomes her husband gushingly, eventually even persuading him to enter his palace by treading over a purple tapestry more becoming for gods than humans. It is a hubristic act, with which Clytemnestra tries to give further justification to what she intends to do next: murder Agamemnon. Left behind, Cassandra, a prophetess cursed not to be believed by anyone, senses this outcome. Even so, she decides to enter the palace as well, believing this to be her inevitable fate. Indeed, it is: Clytemnestra murders both Agamemnon and his lover, and defends this decision before the Chorus as a just act of revenge for Agamemnon having sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia, to appease the gods for a transgression of his own – namely, killing Artemis’ sacred deer. However, that’s not the whole story, as we soon learn from Clytemnestra’s lover (and Agamemnon’s cousin) Aegisthus, who unexpectedly appears on stage. He is in on the murder plot as well, as a way to avenge his brothers, who had been not only slaughtered by Agamemnon’s father, Atreus, but also cooked and served as dinner to Aegisthus’ father, Thyestes. The Argive Elders bemoan this sudden turn of events and warn that Agamemnon’s son, Orestes, will inevitably return to look for vengeance.

Date and Historical Background

Agamemnon is the first play within the Oresteia trilogy, originally performed at the Dionysia festival in 458 BC, where it won the first prize for tragedy. Customarily, the trilogy was followed by a satyr play, in this case one titled Proteus, of which only two lines have survived.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Watchman at the palace of Agamemnon in Argos

• Agamemnon, the king of Argos, returning from Troy after a decade

• Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife

• Cassandra, Trojan princess and war-prize of Agamemnon

• Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin and Clytemnestra’s lover

• Chorus of Argive Elders

• Herald from the Greek forces

Setting

The play is set in front of Agamemnon’s palace at Argos.

Summary of Agamemnon

Prologue

Before the palace of Agamemnon at Argos, ten years after the mighty king left it to lead a Greek army to conquer Troy, a Watchman awaits a night-beacon signal which should announce the fall of the famous Asian city.

Finally, he receives it: “Ah well,” he says to himself, “may the master of the house come home at last, and may I clasp his welcome hand in mine! For the rest I stay silent,” he adds ominously, before descending an inner stairway to pass the news to Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Still faithful to the King, a Chorus of elderly Argives takes the stage, and, in an extended flashback, informs us of quite a few worrisome details regarding the royal family’s history.

The fall of Troy, they say, is a divine punishment for Paris offending Zeus, the overseer of the laws of hospitality, when he abducted Helen, the wife of Agamemnon’s brother, Menelaus.

Unfortunately, Agamemnon too has offended the gods by sacrificing his own daughter, Iphigenia, in an attempt to appease Artemis who, mad at Agamemnon for killing a sacred deer of hers, prevented the winds from blowing and trapped the Greeks in Aulis.

“May she delay the Greek fleet yet again,” the Chorus prays, “and may she refrain from urging another sacrifice, one that knows no law, and is unsuited for feasts... For there abides wrath – terrible, not to be suppressed, a treacherous guardian of the home – wrath that never forgets and that exacts vengeance for a child.”

The implication?

Clytemnestra has never forgiven Agamemnon for sacrificing Iphigenia to Artemis; and she plans to murder him upon his return.

First Episode

Clytemnestra enters the stage in all of her queenly majesty and informs the Chorus that Troy is in the hands of the Achaeans, and that Agamemnon should soon return home.

Though more than cheerful, the Elders ask for a proof, and Clytemnestra replies with a lengthy description of the torch relay which eventually brought the news to the Watchman in the prologue.

Though still a bit skeptical regarding this new method of transmitting the news from the battle, in their second choral song (the first stasimon), the Chorus offers thanksgiving and prayers to the gods all the while lamenting the less fortunate soldiers who laid down their lives under Troy.

Second Episode

Finally, a Herald arrives at the royal palace, and the Argive Elders ask him straightforwardly if the “passing on of flaming lights and beacon signals and fires is true or whether it is merely dream-like beguiling of the senses.”

The Herald confirms Clytemnestra’s story: it is true that the Argives have won and even truer that Agamemnon, bearing light in the darkness to his citizens, is about to disembark on the shore of Argos.

“Oh, greet him well, as is right,” the Herald says, “since he has uprooted Troy with the mattock of Zeus the Avenger, with which her soil has been uptorn.”

Clytemnestra overhears the Argives, and the Herald talking and asks the Herald to give this message to Agamemnon:

“May he come with all his speed back at his palace, may he come to find his beloved wife faithful as he left her, a watchdog of his house, loyal to him, a foe to those who wish him ill; yes, unchanged in every part, never having broken any seal in all this time. Of pleasure from any other man or of scandalous repute – oh, do tell him, – she knows no more than of dyeing bronze.”

The Herald – himself a soldier under Troy, absent for a decade from Greece – knows no better but to believe Clytemnestra’s words. Somewhat afraid of her, the Argive Elders tell him that she was her own interpreter, and then they quickly change the topic, asking the Herald about Menelaus’ fate.

“Don’t mar a joyful day with a tale of misfortune,” says the messenger and, after speckling a few details of Menelaus’ ill-starred journey with hopes for soon return, leaves to convey Clytemnestra’s words to Agamemnon.

Left alone, in their third choral song (second stasimon), the Argive Elders muse over Helen’s betrayal, comparing her to a lion cub raised at home. In a way, the image calls to mind something much more relevant: Clytemnestra is about to betray her husband’s love as well.

A righteous house raises righteous children, the Argives conclude. But evil gives birth to evil – and this is one family that would have been better off childless.

Third Episode

Greeted by the Argive Elders as the Sacker of Troy, Agamemnon royally drives into the city, aboard a majestic chariot and amidst a host of attendants. In the chariot, next to him, stands the tragic figure of Cassandra, Trojan princess and prophetess cursed by Apollo to always be right, but never believed.

As Agamemnon descends from his chariot after giving an appropriate speech to his subjects, Clytemnestra, attended by her maidservants carrying sumptuous purple tapestries, greets her husband in an excessively flattering manner.

It is a chilling encounter, this one: nine years after sacrificing his daughter, Agamemnon returns to Argos with a new bedmate, the gorgeous spoil of war that is Cassandra; and yet, Clytemnestra greets him with fulsome superlatives, and with a sad story about how difficult it is to be the wife of a warrior.

Of course, there are layers and layers beneath her words, with quite a few implicitly referring to Agamemnon’s betrayal and her murdered daughter.

An even more nerve-wracking battle of wits follows, during which Clytemnestra tries to convince her husband to enter his palace treading the purple tapestries, as if a god. At first, Agamemnon refuses, thinking this either too feminine or too unbecoming for a man, but, after some time, he agrees.

A hubristic act, one unbecoming to mere mortals. “Why, why is this terror constantly hovering before my prophetic soul,” sings the Chorus in the third stasimon, sensing doom and reminding everyone that blood guilt is not something Fate forgets or forgives.

Fourth Episode

Speedily, Clytemnestra comes out of the castle to invite Cassandra inside as well, but Cassandra doesn’t respond at all to the invitation. Angry, Clytemnestra goes back indoors, leaving Cassandra behind.

Distraught and grief-stricken, Cassandra falls in a prophetic trance, and in a long, almost dreamlike discussion with the Argive Elders, speaks of the past, the present, and the future of the house, in a sublime language, and in a way which makes it difficult for the reader to understand what has happened and what should unavoidably occur.

Cassandra’s riddling prophecy covers everything from a vision of the ancient sin of Agamemnon’s father Atreus (who slaughtered the children of his brother Thyestes and then served them to him at a feast) to an accurate description of what is happening at the moment inside the palace – namely, a Fury, a demon of bloody vengeance, striking Agamemnon down.

Though Cassandra sees, in her hallucinations, herself being killed as well, she still enters the house – to her doubly tragic but inevitable doom.

To the unsettling tune of shrieks coming from inside the palace, the Chorus of Argive Elders sings of the generational blood-guilt haunting the House of Atreus (fourth stasimon). After realizing what must be happening behind the closed doors, the Elders start discussing what they should do.

Fifth Episode

Suddenly, the door of the palace opens, and Clytemnestra reappears, next to the covered, lifeless bodies of Agamemnon and Cassandra.

“I have done the deed,” she says to the Elders, “and deny it I will not. Round him, as if to catch a haul of fish, I cast an impassable net – fatal wealth of robe – so that he should neither escape nor ward off doom. Twice I struck him, and with two groans his limbs relaxed.”

“When he spurted forth dark drops of blood with his dying breath,” Clytemnestra adds gorily after describing the third and final blow, “I rejoiced just as much as the sown earth when touched by heaven’s refreshing rain at the birthtime of the flower buds.”

Though not necessary, the murder of Agamemnon’s bedmate Cassandra – “an added relish of delight” – adds to Clytemnestra’s triumph: her vengeance is now more than complete; and, in her eyes, it was always a just one.

Exodos (Exit Song)

It is not the justice of this act which concerns the Argive Elders – it is the demon of vengeance they are worried about.

They remind Clytemnestra of past dark deeds, and they express fear that this demon hasn’t been exorcised by the murder of Agamemnon, but merely fattened with some more familial blood.

Things threaten to go out of hand when Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin, appears on the stage. Apparently, Clytemnestra wasn’t alone in this, housing in Agamemnon’s palace as her lover a man who had some seriously unfinished business with her husband.

You see, Aegisthus is one of Thyestes’ sons: it was his brothers that Agamemnon’s father, Atreus, slaughtered and served to his father at a feast.

Now that his vengeance is complete as well – he says to the Argive Elders – he wouldn’t even mind dying but plans to use Agamemnon’s gold to take control of Argos beforehand. The Chorus rebels and Clytemnestra fruitlessly tries to act as an intermediary.

“I will visit you with vengeance yet in days to come,” shouts Thyestes to the Argive Elders. “Not if fate shall guide Orestes to return home,” they reply ominously and prophetically.

A Brief Analysis

Though Aegisthus is the one who, at least in theory, should take control of Argos at the end of the play, it is Clytemnestra who dominates it, and against whose terrifying and larger-than-life figure both Agamemnon and the son of Thyestes seem weak and unimpressive.

“I and you will be masters of this house and order it aright,” she says somewhat subversively to her lover in the final line of the play, after outwitting and murdering her husband and his lover, and unflinchingly defending both of these murders in front of the Argive Elders.

Even the Chorus – who has half of the lines – seems afraid of Clytemnestra for most of the time, and, in fact, it doesn’t really do anything despite sensing trouble from the very start and even after somewhat accurately guessing Cassandra’s prophecies.

Even more tellingly, the Argive Elders aren’t that confrontational with Clytemnestra after the deeds are done: firm believers in the moral law of retribution, it’s almost as if they are more comfortable in the position of observers of some kind of a divine ethical play than interested in taking an active stance.

It is only the appearance of the preening Aegisthus which makes them react; and it is he who is the real (if not only) target of their taunts.

In essence, Agamemnon feels like the wrong title for this play: the king of Argos is a minor character here, and, for large parts, the same holds about all men (Aegisthus, the Argive Elders). As a matter of fact, Cassandra seems like the only character capable of resisting Clytemnestra, the only character as tridimensional as hers.

More than tragic, she embraces her death willingly, possibly deeming it better than slavery.

Agamemnon Sources

There are many translations of Agamemnon available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read Herbert Weir Smyth’s translation for the Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Gilbert Murray rhyming verse adaptation here.

See Also: Oresteia, Libation Bearers, Eumenides, Agamemnon

Agamemnon Video

Agamemnon Associations

Link/Cite Agamemnon Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Agamemnon". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aeschylus/Agamemnon/agamemnon.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.