Eumenides

Eumenides by Aeschylus

First performed in 458 BC, Eumenides is the last play in Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy. It begins in front of the temple of Delphi where, advised by Apollo, Orestes flees at the end of the previous play (Libation Bearers) in an attempt to purify himself of the blood of his mother Clytemnestra. After the ancient goddesses of parricidal vengeance, the Erinnyes, surround him, Apollo orders Orestes to seek protection in the temple of Athena in Athens. Roused by the Ghost of Clytemnestra, the Erinnyes find him there as well. Orestes, claiming that his hands are clean, calls Athena for help, and the goddess returns from Troy to look into the matter. After hearing out both sides, however, she realizes that the problem is too complex to be solved even by a god: Orestes killed Clytemnestra not only to avenge the murder of his father but also because he had been instigated to do so by none other than Apollo; on the other hand, it is the task of the Erinnyes to take revenge in the names of the ones who are unable to avenge themselves. Wise as ever, Athena comes up with a nice solution: she institutes a jury-court of twelve honorable Athenians who are afterward tasked with voting in favor of one of the sides. Even before the result is known, Athena announces that she votes for acquittal so Orestes would be free even in the case of a draw. The tallies are indeed equal at the end, and Orestes is allowed to leave for Argos. The Erinnyes, unsurprisingly, are not happy with the decision and threaten to destroy Athens in Orestes’ stead. Fortunately, Athena mollifies them by offering them a new role – the one of the Eumenides, the kindly protectors of Athens’ prosperity.

Date and Historical Background

Following Agamemnon and Libation Bearers, Eumenides is the last play of the Oresteia trilogy, originally performed at the Dionysia festival in 458 BC, where it won the first prize for tragedy. Customarily, the trilogy was followed by a satyr play, in this case one titled Proteus, of which only two lines have survived.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• The Pythia, the High Priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi

• Orestes, killer of Clytemnestra and suppliant at the Temple of Apollo

• Apollo, the Olympian god of the sun and the arts and the oracular god of Delphi

• The Erinnyes (or the Furies), ancient goddesses of parricidal vengeance

• Ghost of Clytemnestra

• Athena, the Olympian goddess of wisdom and patron goddess of Athens

Setting

The prologue and the first episode of the play are set in front of Apollo’s temple at Delphi; the rest of the play moves to Athens and is primarily played out before the temple of Athena on the Acropolis.

Summary of Eumenides

Prologue

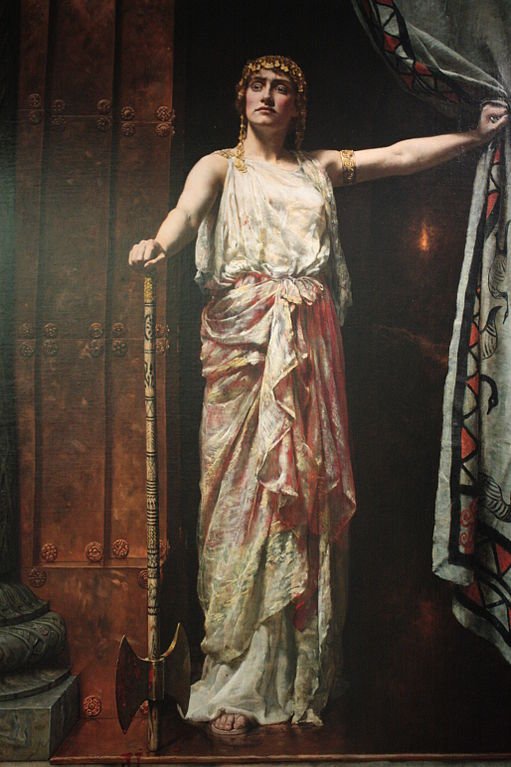

In front of Apollo’s temple at Delphi, the Pythia (Apollo’s Prophetess) customarily prays to the gods and goddesses of the sanctuary before entering the building. After a very brief interval, she returns terror-stricken.

“Horrors to tell, horrors for my eyes to see,” she exclaims, “have sent me back from the house of Apollo, so that I have no strength and I cannot walk upright.”

Inside, we learn, on the center-stone (the so-called navel of the world), there is a man “defiled in the eyes of the gods… his hands dripping with blood and holding a new-drawn sword,” decorated with an olive branch and large tuft of wool.

Even more frightening, around him there are women, seated on chairs, more similar in their appearance to Gorgons than to humans: “wingless, black, altogether disgusting; they snore with repulsive breaths, they drip from their eyes hateful drops; their attire is not fit to bring either before the statues of the gods or into the homes of men.”

Apollo’s Priestess exits, and the doors of the temple open.

We see Apollo swearing before Orestes that he would never abandon him and ordering him to flee to Athens and seek sanctuary in Athena’s temple there. After a brief discussion, Orestes leaves, escorted by none other than Hermes; Apollo exits as well.

And then, out of nowhere, the ghost of Clytemnestra appears. She wakes the sleeping Erinnyes and accuses them of apathy and disrespect: “although I have suffered cruelly from my nearest kin,” she tells them, “no divine power is angry on my behalf.”

Roused by their leader, the moaning and groaning Erinnyes awake, one by one; they regroup and form the play’s chorus.

First Parodos (First Entrance Song)

In the first choral song of Eumenides, the Erinnyes express their disgust at the deeds of these new, unjust gods, blaming Apollo for helping “a godless man and a son cruel to a parent” get away with a vicious murder that has polluted with unclean blood his very temple.

They vow to revenge upon Orestes: “he shall not win his release; even if he escapes beneath the earth, he will never be set free.”

First Episode

“Out, I order you!” shouts Apollo at the Erinnyes. “Go away from this house at once, leave my prophetic sanctuary – or else.”

However, the Erinnyes won’t have it: we haven’t done anything wrong, they say, but you and Orestes have. Even more: in their eyes, Apollo is more than just partially guilty of the crime, since he had both directed Orestes to kill his mother and agreed to give the murderer a refuge in his temple.

“We will never, never leave that man!” shriek the Erinnyes and swiftly leave for Athens to hunt Orestes down. Apollo, vowing to save him, follows.

The scene, abruptly and in mid-episode, changes: we are now before the temple of Athena on the Athenian Acropolis and see Orestes formally appealing to the goddess for protection. Barely is his prayer done when the Erinnyes surround him yet again.

Second Parodos (Second Entrance Song)

The Chorus, absent for half a scene, reenters the stage but this time it seems more determined than ever. “A mother’s blood is hard to recover,” they sing, and “it can only be repaid with red blood from living limbs.”

“We are thirsty for this gruesome drink,” they add, dogged in their desire to wither Orestes away bloodless, and drag him down to Hades so that he pays atonement for the agony of Clytemnestra.

Second Episode

Orestes begs to differ: he says to the Erinnyes that his hard life has taught him quite a few purification rituals and that the pollution of his mother’s killing has now been washed away by none other than Apollo.

“So now with a pure mouth, I piously invoke Athena, lady of this land, to come to my aid,” Orestes concludes, expressing his hope that the goddess and her city will side with him against the wrath of the Erinnyes.

The first stasimon (the third choral song) is a powerful binding-song: the Erinnyes pray to their mother Nyx (Night), pronounce their duties as goddesses of revenge and justice and express their determination to protect their Fate-given office and their birthrights.

Third Episode

Even though in Troy – where she had been taking possession of the land – Athena hears the call of Orestes summoning her and arrives in her city. After learning the identities of the persecutors and her most recent suppliant, she listens to the complaints of the Erinnyes and Orestes’ defense.

However, upon hearing the accusations, Athena announces that “the matter is too great” and that “it is not lawful ever for [her] to decide on cases of murder that are followed by the wrath of the Erinnyes.”

Either way, she says, brings disaster to her: if she allows the Erinnyes to avenge Clytemnestra, her hands would be stained with the blood of an Apollo-backed suppliant who hasn’t brought harm to her city; if, however, she doesn’t, the venom of the Erinnyes’ resentment will fall upon the ground, bringing “an intolerable, perpetual plague afterward in the land.”

So, Athena decides to institute a jury-court of oath-bound citizens to settle the matter.

“Summon your witnesses and proofs,” she says to Orestes and the Erinnyes, “sworn evidence to support your case; and I will return when I have chosen the best of my citizens, for them to decide this matter truly, after they take an oath that they will pronounce no judgment contrary to justice.”

In the second stasimon (fourth choral song), the Erinnyes express their displeasure at this decision, warning everybody that if Orestes gets away with matricide, then anarchy is merely a step away. “There is a time when fear is good and ought to remain seated as a guardian of the heart,” they sing. “It is profitable to learn wisdom under strain.”

Fourth Episode

At the Areopagus-hill near the Acropolis, before the watchful eye of the public, the trial of Orestes solemnly begins, with him as the defendant, the Erinnyes as the prosecutors and Athena as the judge presiding over a group of citizen jurors; though represented primarily as a witness, Apollo, in more than one way, acts as Orestes’ lawyer.

Unsurprisingly, he is the one who presents the deciding argument: the Erinnyes are tasked with avenging parricides, but “the mother of what is called her child is not the parent, but the nurse of the newly-sown embryo.”

In other words, a mother merely safeguards the child whose only parent is the one who scatters the seed. As proof that a child can have only a father, Apollo offers the very judge: born out of Zeus’ head, Athena “was not nursed in the darkness of a womb, and she is such a child as no goddess could give birth to.”

After Apollo’s argument, Athena calls for the verdict, announcing that, since she is indeed motherless and favors men more than women, she gives her vote for Orestes so he would win even if the tallies are equal.

They are – so Orestes is acquitted and, before leaving for Argos, promises the city of Athens’ eternal gratitude and unconditional alliance.

Shocked and dishonored, the Erinnyes redirect their anger toward Athens, threatening to release venom from their hearts and unleash destruction on the glorious city.

Fortunately, Athena intervenes and gradually manages to persuade them to give up their fury, by promising them a new home in the caves under the Areopagus and a permanent cult in Athens, the “land that is most beloved to the gods.”

Exodos (Exit Song)

The Erinnyes accept Athena’s offer and, in a joyful song, they and the goddess describe this new role, which, in addition to their previous office (deterring parricidal conflict) includes ensuring the fertility of the land of Athens and that of its law-abiding citizens.

At the end of the play, Athena asks her attendants to escort the Erinnyes to their new home, and the audience learns their new name as well: the once-feared Erinnyes have now become the Eumenides of the title, the Kindly Ones.

A Brief Analysis

Eumenides is more than a fitting finale to, arguably, the greatest literary trilogy in human history, not only because it aptly resolves all of the seemingly irresolvable problems postulated in the first two plays (Agamemnon and Libation Bearers), but also because it does so in a highly topical, and yet unobtrusive manner.

Merely four years before the first production of Oresteia, Athens signed a controversial treaty with Argos, and, in Eumenides, Aeschylus provides it with a mythological etiology (and authority), using the acquittal of Orestes as an excuse for Athens allying with the Argives even though they took no part in the Persian War (possibly even making a secret agreement with the Asian invaders) and were not in particularly amicable relationship with Athens.

The First Peloponnesian War had started two years before the first performance of Oresteia, and it is quite possible that Eumenides comments upon this fact as well. After all, the war brought Athens to the brink of a civil war, and it is not coincidental that in the exit song of the chorus, the newly-invented goddesses of Athenian fertility and prosperity sing thus: “I pray that discord, greedy for evil, may never clamor in this city, and may the dust not drink the black blood of its people and through passion cause ruinous murder for vengeance to the destruction of the state.”

462 BC was also the year when Ephialtes reformed the hitherto notoriously conservative Areopagus in the bastion of radical democracy for which Athens would become famous. It is not a stretch to say that Aeschylus approving these reforms in an award-winning trilogy (the Areopagus is depicted as a divine gift to be cherished) may have played a vital role in the creation, evolution, and preservation of modern democracy.

However, the most significant creative feat of Eumenides (and the Oresteia in general) is the unexpected ending, when, for the first time in history, Aeschylus equates the vengeful Erinnyes with the kindhearted Eumenides. This is not just a simple twist, but a symbolic representation of a major ethical shift, the imaginative correction of the universe’s moral structure. The gods, whispers Aeschylus, have grown incapable of solving humankind’s problems and must make their way for something much more just and much smarter: human communities.

Eumenides Sources

There are many translations of Eumenides available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read Herbert Weir Smyth’s translation for the Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into E. D. A. Morshead verse adaptation here.

See Also: Oresteia, Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, The Erinnyes

Eumenides Video

Eumenides Associations

Link/Cite Eumenides Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Eumenides". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aeschylus/Eumenides/eumenides.html. Accessed 17 April 2024.