Oresteia

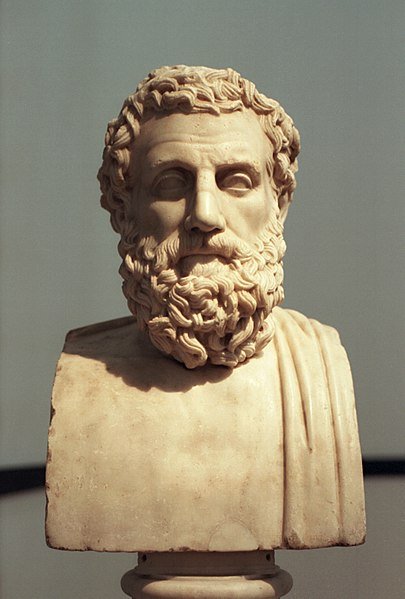

Oresteia by Aeschylus

Even though it was customary to present dramatic trilogies at the Dionysia festivals of Ancient Greece, Aeschylus’ Oresteia is the only complete Ancient Greek trilogy which has survived to this day. Just like many (if not most) of Aeschylus’ trilogies, it is a connected one: the three plays which comprise it – Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, and Eumenides – are continuous in plot and unified in subject matter. They revolve around the curse on the House of Atreus, recounting a horrific story of revenge and familial bloodshed, from the murder of Agamemnon by his wife Clytemnestra (Agamemnon) through the murder of Clytemnestra by her son Orestes (Libation Bearers) to the trial and acquittal of Orestes by means of a new institution: the jury-court at the Areopagus (Eumenides). Lauded by both ancient and modern critics, Oresteia won the first prize for tragedy at the Dionysia festival in 458 BC and has been translated and adapted countless times. The text of its three plays – writes Christopher Collard in the “Preface” to his translation of the trilogy – is “so rich in every way that the Oresteia has excited the most detailed technical commentaries and the most profuse critical discussion of any work of its kind from Classical antiquity, more even than Sophocles’ Oedipus the King; its stature as dramatic poetry is comparable for example with that of Hamlet or Faust.”

Summary of Oresteia

To learn more about the historical background and the characters of Agamemnon, Libation Bearers and Eumenides, and to read a scene-by-scene summary of these plays in addition to play-specific analyses, please consult the articles of the individual plays.

Agamemnon

Agamemnon is set in front of the palace of Argos. At the beginning of the play, a Watcher notices a beacon fire signal which announces the return of Argos’ king, Agamemnon, ten years after sailing away to conquer Troy. The information is subsequently confirmed by a Herald, soon after which Agamemnon arrives in a chariot. Next to him is Cassandra, the Trojan princess, a spoil of war and a new bedmate of Agamemnon.

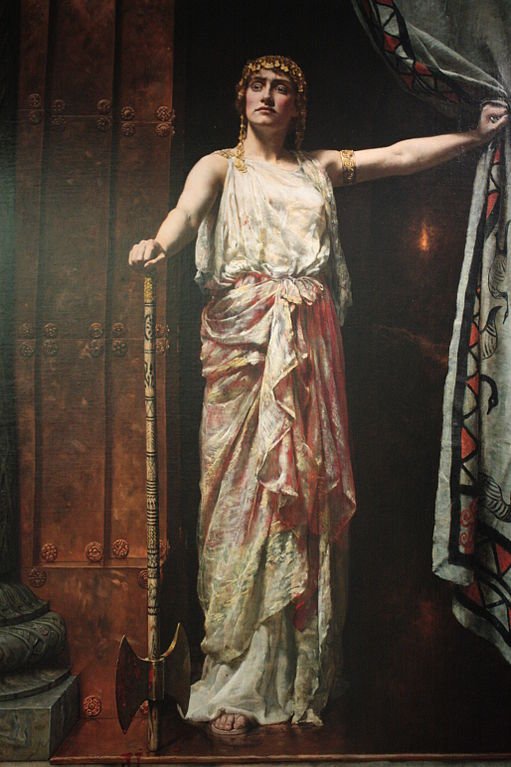

Regardless of this, Clytemnestra enthusiastically welcomes her husband, overgenerous in her compliments and prideful in her own faithfulness. Eventually, she even persuades her husband to enter his palace by treading over a purple tapestry, one that seems much more suitable for gods than for humans. It is a trick: by coaxing her husband into acting hubristically, Clytemnestra tries to justify herself before the gods for what she intends to do next – namely, murder Agamemnon.

Cassandra, a prophetess cursed by Apollo not to be believed by anyone, senses this outcome. Even so, she decides to enter the palace as well, believing this to be her inevitable fate. Indeed, it is: Clytemnestra murders both Agamemnon and her, and defends this decision before the Chorus of Argive Elders as a just act of revenge for Agamemnon having sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia, to appease the gods for a transgression of his own – killing Artemis’ sacred deer.

However, that’s not the whole story, as we soon learn from Clytemnestra’s lover (and Agamemnon’s cousin) Aegisthus, who unexpectedly appears on stage. He is in on the murder plot as well, as a way to avenge his brothers, who had been not only slaughtered by Agamemnon’s father, Atreus, but also cooked and served as dinner to Aegisthus’ parent, Thyestes. The Argive Elders bemoan this sudden turn of events and warn that Agamemnon’s son, Orestes, will inevitably return to look for vengeance.

Libation Bearers

Once again set before the palace of Argos, the Libation Bearers starts where Agamemnon leaves off – only several years into the future.

Commanded by the god Apollo and accompanied by his friend Pylades, Orestes, the only son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, returns to his father’s court to avenge his murder. At the beginning of the play, he stops by at the tomb of Agamemnon – located just in front of the palace – and makes an offering. Noticing a group of women approaching the tomb with apparently the same mission, Orestes withdraws, only to recognize his sister Electra among the libation bearers. After he hears her cursing their mother and praying for his very return, Orestes reunites with her sister, and with her help, devises a plan on how to kill Clytemnestra.

Soon after, Orestes and Pylades start enacting the plan: disguised as far-away guests, they gain access to the royal palace by announcing the supposed death of none other than Orestes. Clytemnestra hears the news first and sends a servant – Orestes’ nurse when he was a baby – to relay it to Aegisthus; tricked by the slave-women, the nurse tells Aegisthus to talk to the guests in person and alone. He does precisely that, but, instead of being fed the joyful news, is promptly murdered.

Becoming conscious of the identity of the guests, Clytemnestra begs her son not to kill the woman who has breastfed him. However, in his only words of the play, Pylades reminds Orestes of Apollo’s directive, and he slays Clytemnestra. It is no more than a brief triumph: shortly after the murder, Orestes starts hallucinating, seeing in his mind’s eye the Erinnyes, the infernal goddesses of vengeance, swarming around him and thirsty for his blood. Fearing for his sanity, he rushes off to find protection in Apollo’s temple at Delphi.

Eumenides

Inside Apollo’s temple at Delphi, the ancient goddesses of parricidal vengeance, the Erinnyes, surround the sleeping and tired Orestes. At the order of Apollo, Orestes flees Delphi as well to seek protection elsewhere: more precisely, in the temple of Athena in the goddess’ city of Athens. Roused by the Ghost of Clytemnestra, the Erinnyes find him there as well.

Orestes, claiming that he is now purified of his mother’s blood, calls Athena for help, and the goddess returns from Troy to look into the matter. After hearing out both sides, however, she realizes that the problem is just too complex to be solved – even by a god. In short, Orestes killed Clytemnestra not only to avenge the murder of his father but also because he had been instigated to do so by none other than Apollo; on the other hand, it is the main task of the Erinnyes to take revenge in the name of the ones who are unable to avenge themselves – especially when their death is brought upon by a member of their family.

Wise as ever, Athena comes up with an elegant solution: she institutes a jury-court of twelve honorable Athenians who are afterward tasked with voting in favor of one of the sides. Even before the result is known, Athena announces that she will vote for acquittal, meaning Orestes would end up free even in the case of a draw.

The tallies are indeed equal at the end, and Orestes is allowed to leave for Argos. The Erinnyes, unsurprisingly, are not happy with the decision and threaten to destroy Athens in Orestes’ stead. Fortunately, Athena mollifies them by offering them a new role – the one of the Eumenides, the kindly protectors of Athens’ prosperity.

Proteus

In the fifth century BC, each tragic poet was expected to present, in addition to a (connected or unconnected) trilogy, a satyr play as well. Unlike the tragedies preceding it, the satyr play was mostly comical by nature, and bawdy by character, and, in more ways than one, reminiscent of a more modern theatrical invention: the burlesque.

Even though only one satyr play has survived in its entirety to this day (Euripides’ Cyclops), the ancient geographer Pausanias notes in his Description of Greece that Aeschylus’ satiric plays were more popular than anyone else’s. Unfortunately, we know little more than the title of the satyr play which followed the Oresteia tragic trilogy (Proteus) because nothing save a single fragment of two lines (plus one half-line and four isolated words) has been preserved to this day.

However, we can guess, with reasonable certainty, that it dramatized the adventures of Agamemnon’s brother Menelaus in Egypt, for two reasons. Firstly, in the second episode of Agamemnon, the Herald mentions specifically that he does not know whether or not Menelaus’ ship has survived; and secondly, in the fourth book of Homer’s Odyssey, we are informed that Menelaus ends up on the island of Pharos, the home of the “unerring old man of the sea, the immortal Proteus of Egypt.”

Anything more than this is pure speculation; not that it has stopped modern scholars from attempting to reconstruct the play from scratch.

A Brief Analysis

Even though Oresteia is cosmic in scope and explores numerous topics, the two major themes of the trilogy – as suggested by Ian Christopher Storey and Arlene Allan – are the shifting notion of justice and the gender conflict.

The Birth of a New Dike (Justice)

“If there is serious injury,” one reads in Exodus 21:24, “you are to take life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth.” As many have noted, this Biblical injunction can be used as a simplified description of the moral universe Aeschylus explores and challenges throughout the plot of Oresteia. In fact, quite a few verses in the trilogy say pretty much the same, as, for example, Clytemnestra’s apology for the murder of Agamemnon before the Argive Elders, which, translated by E. D. A. Morshead, mirrors another Biblical dictum (Matthew 26:52): “By the sword his sin he wrought,/ And by the sword himself is brought/ Among the dead to dwell.”

In this “eye for eye” moral universe, it is difficult to make the distinction between those who wrong and those who are wronged. Clytemnestra cannot be blamed for thinking that the death of Agamemnon is neither ignoble nor unjust, because, after all, it was he who “by treachery brought ruin on his house,” willingly sacrificing his “much lamented” daughter Iphigenia only so that he is able to earn immortal fame and become the conqueror of Troy. But, as we learn through the words of the Chorus, neither did Agamemnon have a choice: he sacrificed Iphigenia to make amends to Artemis for killing her sacred deer. The matters get even more complicated in Libation Bearers when Orestes chooses to act as Apollo’s divine agent and avenge the murder of his father by killing his mother. Unfortunately, even Apollo’s intrusion doesn’t bring an end to the vicious circle of violence, as almost immediately after killing his mother, Orestes sees the Furies, the ancient parricidal retaliators.

What Athena, the goddess of wisdom, realizes in Eumenides, the final play of the trilogy, is something supposedly uttered by Mahatma Gandhi two and a half millennia later: “an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind.” Namely, even if justified, in the long run, the old law of retaliation is just too costly for the community, since any murder would naturally result in many more. Consequently, the never-ending cycle of revenge is appropriately replaced by civic justice, a newly instituted court of law whose word should be final on all matters, bringing them to an indisputable end – one that will have to be accepted not only by mortals but by gods as well.

The Gender War

Beneath the war for justice, there’s another war going on throughout Oresteia: the gender conflict between males and females of power.

And it is announced early on in the trilogy, in the very first speech by the Watcher, who describes Clytemnestra pretty much the same way Shakespeare would Lady Macbeth many, many years later: “woman in passionate heart and man in strength of purpose.” (Morshead’s translation echoes Queen Elizabeth I’s speech to the troops at Tilbury: “She in whose woman's breast beats heart of man.”) All through Agamemnon (and for much of Libation Bearers), Clytemnestra justifies this description with her actions, dominating all the men around her (even her lover Aegisthus), only to be eventually killed by none other than the man she breastfed. Afterward, Orestes is attacked by the female goddesses of revenge, the Erinyes.

Interestingly, the gender conflict is finally resolved by a woman – the goddess Athene – but not in favor of women. On the contrary: the very fact that Athene doesn’t have a mother is used as an argument in support of Apollo’s and Orestes’ claim that a mother is less of a parent than a father, and, thus, punishing a matricide is beyond the moral realm of the Erinyes. Athena agrees with this assessment and votes for the acquittal of Orestes; her vote turns out to be the deciding one.

However, the final decision results not only in the exoneration of Orestes, but also in the redefinition of some gender boundaries: the ferocious and volatile Erinyes, “the bloodhounds of Clytemnestra’s hate,” are transformed into the Kindly Eumenides, the goddesses of prosperity and fertility – yet another victory for the ancient patriarchal structures of power.

Oresteia Sources

You can read E. D. A. Morshead’s translation of Oresteia here. See the “Sources” sections of each of the individual plays for further links to respective translations. To read Pausanias’ note on Aeschylus’ satyr plays in its original context, click here.

See Also: Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, Eumenides, Aeschylus

Oresteia Video

Oresteia Associations

Link/Cite Oresteia Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Oresteia". GreekMythology.com Website, 30 Sep. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aeschylus/Oresteia/oresteia.html. Accessed 24 April 2024.