Libation Bearers

Libation Bearers by Aeschylus

First performed in 458 BC, Libation Bearers is the second play in Aeschylus' Oresteia trilogy, preceded by Agamemnon and followed by Eumenides. The play is set in front of the palace of Argos, where, many years after the murder of his father Agamemnon by his mother Clytemnestra and her partner, Aegisthus, Orestes returns from exile to exact vengeance, commanded by the god Apollo. Accompanied by his friend Pylades, he stops by at the tomb of his father – located just in front of the palace – and makes an offering. Noticing a group of women approaching the tomb with apparently the same mission, Orestes withdraws, only to recognize his sister Electra among the libation bearers, cursing their mother and praying for his return. The two reunite and devise a plan on how to kill Clytemnestra. Soon after, Orestes and Pylades start enacting the plan: disguised as far-away guests, they gain access to the royal palace by announcing the supposed death of Orestes. Clytemnestra hears the news first and sends a nurse to relay it to Aegisthus; tricked by the slave-women, the nurse tells Aegisthus to talk to the guests in person and alone. He does precisely that, but, is, instead, promptly murdered. Becoming conscious of the identity of the guests, Clytemnestra begs her son not to kill the woman who has breastfed him. However, Pylades reminds him of Apollo’s directive, and Orestes slays Clytemnestra as well. It is no more than a brief triumph: shortly after the murder, Orestes starts hallucinating, seeing in his mind’s eye the Erinnyes, the infernal goddesses of vengeance, swarming around him and thirsty for his blood. Fearing for his sanity, he rushes off to find protection in Apollo’s temple at Delphi.

Date and Historical Background

Libation Bearers is the second play within the Oresteia trilogy, originally performed at the Dionysia festival in 458 BC, where it won the first prize for tragedy. Customarily, the trilogy was followed by a satyr play, in this case one titled Proteus, of which only two lines have survived.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Orestes, son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, returning from exile

• Pylades, Orestes’ close friend

• Electra, Orestes’ sister

• Clytemnestra, the queen of Argos; Orestes’ mother and Agamemnon’s wife and murderer

• Aegisthus, the king of Argos and Clytemnestra’s coconspirator and lover; also, Orestes’ uncle

• Chorus of women-slaves from the palace

• Cillisa, Orestes’ nurse when he was a baby

• Servant of Aegisthus

Setting

Just like Agamemnon, Libation Bearers is set in front of the royal palace of Agamemnon at Argos.

Summary of Libation Bearers

Prologue

Many years after the murder of his father, in the company of his friend Pylades, Orestes returns from exile home to Argos and visits the grave of Agamemnon; as he lays out a devotional lock of his hair on the tomb, he hears a group of wailing women approaching.

He recognizes his sister Electra among them and, in an attempt to understand more about their reasons without becoming too suspicious, he and Pylades hide near the tomb.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Accompanied by Electra, a Chorus of slave-women – the Libation Bearers from the title – makes offerings to Agamemnon’s tomb.

In their first choral song (the parodos), the slave-women reveal that they have been directed by Clytemnestra, who, frightened by the meaning of a disturbing nightmare from the night before, has sent them there in the hope that they should appease the wrath of her murdered husband.

The bearers, however, are afraid to utter the words Clytemnestra has asked them too: calling her “a godless woman,” they offer the libations to Agamemnon with a prayer that “the balance of Justice” is restored in the House of Atreus.

First Episode

The first episode of Libation Bearers takes about half of the play’s length, and it can conveniently be divided into three scenes.

Recognition Scene

The first one of these three is famously known as the recognition scene. In it, after mourning her father, cursing her mother, and praying for her brother, the vengeance-hungry Electra notices a lock of hair on Agamemnon’s grave and a few foot-traces in the ground.

She compares the lock to her own hair and the traces’ length to her feet and realizes that they must belong to someone she is related to. Before she could discern some more, Orestes comes out of the shadows with Pylades. “You see before you the one you have long prayed for,” he says.

After a joyful reunion, Orestes reveals to Electra that he has been sent to Argos by none other than Apollo, hungry for the blood of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus.

Kommos

Electra celebrates the news and, in the second scene of the first episode (kommos), she and her brother join the Chorus in a grand incantation for Agamemnon’s help.

In the song, the siblings and the slave-women express their allegiance to Agamemnon and summon his spirit, all the while recreating the moral universe of Agamemnon: “a murderous stroke let a murderous stroke be paid,” they sing, “let it be done to him as he does.”

The Plan

After they finish their chant, the siblings and the Chorus start planning out the murder of Clytemnestra.

Though still a bit uneasy, Orestes is further encouraged to it by the details of the above-mentioned dream of Clytemnestra: as the Chorus reveals, in this nightmare, the queen gave birth to a snake which then “drew in clotted blood with the milk.”

“Well then,” exclaims Orestes, “I pray to this earth and to my father's grave that this dream may come to its fulfilment in me.”

“As I understand it,” he goes on, “it fits at every point. For if the snake left the same place as I; if it was wrapped in my swaddling clothes; if it sought to open its mouth to take the breast that nourished me and mixed the sweet milk with clotted blood while she shrieked for terror at this – then surely, as she has nourished a portentous thing of horror, she must die by violence. “

“For I,” Orestes concludes ominously, “I, turned serpent, am her killer.”

A few moments later, Clytemnestra’s children devise a plan: Orestes and Pylades will camouflage themselves as guests to enter the palace and, once inside, they will murder the royal couple.

Electra’s part is marginal – she merely needs to watch and warn; her subsequent entrance in the palace signals her exit from the play altogether: after this scene, Electra is not seen again until the end of the trilogy.

Left alone, the Chorus sings of the bravery of men and the deceitfulness of women, comparing Clytemnestra to other “murderous maidens” from history and mythology, such as the monstrous Scylla and Althaea.

Second Episode

Disguised as a traveler, Orestes deceives his mother into offering him and his friend Pylades hospitality by falsely announcing his own death.

Just as falsely, Clytemnestra laments for a brief moment before expressing her intention to share the sad news with her husband, Aegisthus. In truth, she is more than relieved: the news allays the fears that have haunted her since her nightmare.

Soon after Clytemnestra retires to her chamber, Orestes’ old Nurse – often named Cilissa – appears on the stage, mourning the death of her lost darling and remembering his childhood innocence.

Upon finding out that she is sent by Clytemnestra to relate the news to Aegisthus, the Chorus persuades her to tell him that he should hear the news straight from the guests and that he should come alone to do so.

“For in the mouth of a messenger a crooked message is made straight,” the slave-women reason, suggesting that Aegisthus may not really understand the message unless he hears it from the horse’s mouth, i.e., the guest who first announced it.

After successfully tricking the Nurse, in their third choral song (second stasimon), the slave-women pray again, comparing Orestes to Perseus and Clytemnestra to Medusa.

Third Episode

“I have come not unasked but summoned by a messenger,” says Aegisthus as he is about to enter the palace in discussion with the slave-women. “I heard startling news told by some strangers who have arrived, tidings far from welcome – that Orestes is dead.”

“We heard the tale, it is true,” lies the Chorus. “But go inside and inquire of the strangers. The certainty of a messenger's report is nothing compared with one's own interrogation of the man himself.”

Soon after Aegisthus enters the palace, shrieks of pain are heard from the inside, and a wounded servant rushes outside to warn Clytemnestra.

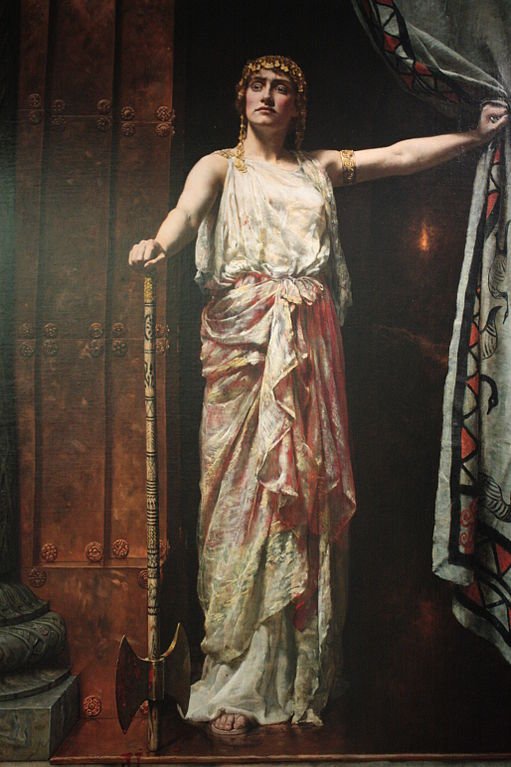

“Ah! Indeed, I grasp the meaning of the riddle,” says Clytemnestra and asks that someone gives her an ax as quickly as possible. Orestes is, however, quicker and confronts her with a blood-dripping sword.

Baring her breast, Clytemnestra pleads for her life: “Have pity, child,” she says, “upon this breast at which many times while you slept you sucked with toothless gums the milk that nourished you.”

Orestes hesitates: “Shall I spare my mother out of pity?” he asks Pylades.

In his only spoken words, Orestes’ friend reminds him of Apollo’s command and advises him to “count all men as enemies rather than the gods.”

Orestes concurs.

Followed by his friend, he takes Clytemnestra inside; the door closes.

“Justice has come,” sing the slave-women in the third stasimon, expressing their hope that with the Apollo-approved murder of Clytemnestra the House of Atreus may finally be freed from the evil demon that has haunted it for so many decades.

Exodos (Exit Song)

In a scene mirroring Clytemnestra’s triumph at the end of Agamemnon – the queen gloating over her murdered husband and his lover – Orestes is now shown standing victoriously over the lifeless bodies of his mother and her lover.

Once again, however, the triumph is more than brief: before he can try to explain his actions before the gathered citizens of Argos, Orestes starts slipping into madness, hallucinating the presence of the vengeance-thirsty goddesses, the Erinnyes.

“Ah, ah!” he shrieks in disgust to the Chorus of slave-women. “You handmaidens, look at them there: like Gorgons, wrapped in sable garments, entwined with swarming snakes!”

After realizing that he is the only one who can see them, Orestes understands that they must have come for him, so he flees to seek refuge in Apollo’s temple at Delphi.

A Brief Analysis

As it has been pointed out numerous times, the Oresteia takes the form of action à reaction à resolution; so, if Agamemnon was the ‘action’ (Clytemnestra killing Agamemnon), Libation Bearers is the ‘reaction’ (Orestes killing Clytemnestra).

However, even at the end of Libation Bearers, resolution seems far from attainable, mainly because the reader gets the feeling that Orestes has no more right to kill his mother than she had to kill her husband. Both are acts of just vengeance: Orestes kills his mother for the murder of his father, but Clytemnestra has only killed Agamemnon because he had previously sacrificed Iphigenia.

That being said, there is one significant difference: unlike Clytemnestra who takes the divine law in her hands, both Agamemnon and Orestes – in killing a female member of their family (Iphigenia and Clytemnestra) – have been commanded by a god to do so (Artemis and Apollo).

The fact that Orestes rushes away to a sacred temple at the end of Libation Bearers (something Clytemnestra could not do at the end of Agamemnon) gives some hope. Namely, if the humans are incapable of freeing themselves from the never-ending eye-for-an-eye cycle of violence, maybe the gods will help them find a way out?

Libation Bearers Sources

There are many translations of Agamemnon available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read Herbert Weir Smyth’s translation for the Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Gilbert Murray rhyming verse adaptation here.

See Also: Oresteia, Agamemnon, Eumenides, Orestes

Libation Bearers Video

Link/Cite Libation Bearers Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Libation Bearers". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aeschylus/Libation_Bearers/libation_bearers.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.