Suppliants

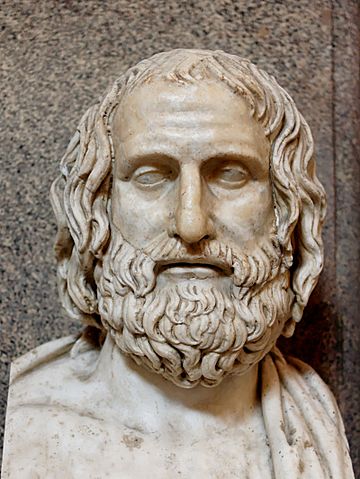

Suppliants by Euripides

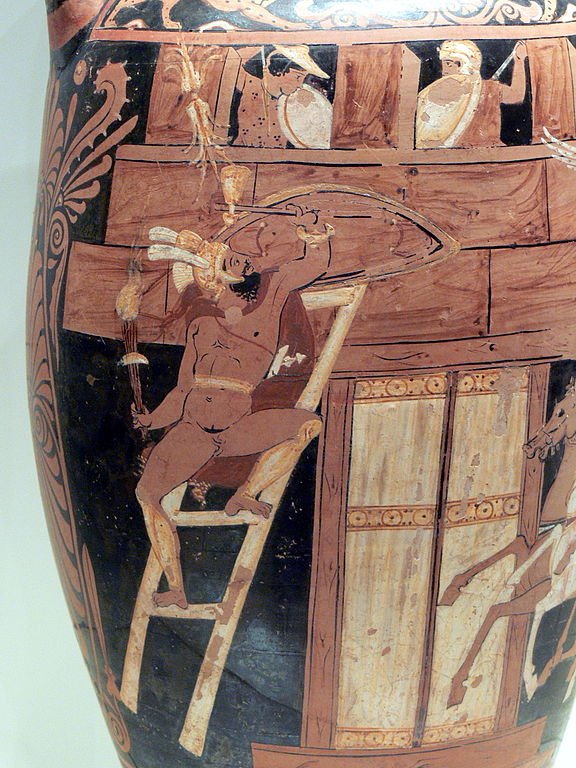

First produced sometime between 425 and 418 BC—and sharing some ideological similarities with his earlier work, Children of Heracles—Suppliants is perhaps the most overtly political and the most unambiguously patriotic play in Euripides’ oeuvre. It is set before the temple of Demeter at Eleusis in Attica, where the mothers of the dead Argive invaders of Thebes, led by the only surviving member of the Seven, Adrastus, have arrived in search of sanctuary and some help from Athens’ king Theseus to recover the bodies of their sons lying unburied on the fields before Thebes. They are initially met by Aethra, Theseus’ mother, and then by Theseus himself. Though Theseus, at first, rejects the request on account of the fact that the attack on Thebes by the Seven was an act of impious aggression, he is afterward persuaded by the sympathetic Aethra to change his mind. Just at this moment, a herald sent by Creon, the king of Thebes, arrives at the temple of Demeter and warns Theseus that any help given to the Argive mothers would be interpreted as a proclamation of war by Thebes. This is precisely what follows: Theseus leads his army to Boeotia and, as a messenger informs the grieving Argive women soon after, emerges victorious from a costly fight. Not much time passes before the bodies of five of the Seven Against Thebes are brought back to Athens. Adrastus, who has survived this second attack as well, delivers a touching eulogy while the funeral pyres are being prepared. Unable to bear the pain of seeing him eternally engulfed by the flames, Evadne, wife of one of these five Argive leaders (Capaneus), leaps upon his funeral pyre before the eyes of her inconsolable father, Iphis. The play ends with a promise from Adrastus that, in gratitude for this favor, Argos would forever remain a friend of Athens, an allegiance blessed by the goddess Athena herself who, after appearing quite without warning, additionally encourages the sons of the Seven to end what their fathers had started and conquer Thebes.

Date and Historical Background

Of the 18 surviving plays of Euripides, ancient introductions (hypotheses) have provided us with the secure dates for 9, and a number of techniques—from allusions to external events to Euripides’ metrical practice—have helped scholars date the remaining plays to within one or two years.

The only exception is Suppliants, which has been dated as early as 425 and as late as 416. However, based on its prosodic nature and supposed political relevance—for more see our brief analysis below—most scholars usually date it to 423-420, deeming the first half of this four-year period (423 or 422 BC) more probable than the latter.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Aethra, mother of Theseus

• Theseus, king of Athens

• Adrastus, king of Argos, one of the Seven Against Thebes

• Evadne, wife of Capaneus and sister of Eteoclus, both of them members of the Seven

• Iphis, father of Evadne and Eteoclus

• Herald of Creon, king of Thebes

• Messenger coming from Thebes, a former servant of Capaneus

• Athena, goddess of wisdom and warfare

• Chorus of the mothers of the Argive dead at Thebes

• Chorus of Argive boys

Setting

The temple of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis in Attica.

Summary of Suppliants

Prologue

Not too long before the beginning of Suppliants—as masterfully depicted in Aeschylus’ play Seven Against Thebes—an Argive army led by Polynices attacked Thebes at the time ruled by his brother, Eteocles, and decisively lost. Six of the seven captains of the Argive army never returned to their homes. Moreover, owing to the strict orders by Thebes’ new ruler Creon, all of their bodies have been left to rot away under the Theban sun: burying them, as Antigone would find out in the same-titled play by Sophocles, is punishable with death under Creon’s decree. In an attempt to find some help to recover the bodies of his friend, Adrastus, the only surviving member of the Argive expedition in Thebes, gathered the mothers of the dead and led them to Eleusis, Athens.

It is here, at the temple of Demeter, that Suppliants begins, with Aethra, mother of the Athenian king Theseus, bemoaning the fate of her town’s unfortunate guests. She had been on her way to the shrine to make a ritual sacrifice but instead happened upon Adrastus and the Argive mothers. Sympathetic to their plight, she has sent her herald to the city to call her son in hope that he might know what’s the proper thing to do at the present moment.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The Argive mothers are impatient, and they can’t stop begging Aethra for help. “You too, honored lady, once bore a son,” one of them says. “Share, share with me your feelings, in such measure as my sad heart grieves for my own dead sons; and persuade your son, o, we implore you, to go unto the river Ismenus, and place within my arms the bodies of the dead, slain in their prime and wandering without a tomb.”

First Episode

The Argive mothers are still crying when Theseus arrives at the temple of Demeter. Surprised to see his mother sitting at the altar surrounded by so many foreign women, he immediately asks Aethra what is going on. She says that she knows but that “it is for them to tell their story.” Theseus, noticing the man in the company, turns immediately to Adrastus: “To you, in your mantle muffled, I address my inquiries; unveil your head, let lamentation be, and speak; for nothing can be achieved save through the utterance of your tongue.”

What follows is a series of questions by Theseus that allow Adrastus to tell his story. He explains that he was one of the Seven commandeers who attacked Thebes and that he did it out of respect for his sons-in-law Tydeus and Polynices—both of them Thebans banished from their hometown, both of them resolute to take revenge. However, he adds, he also did it in spite of the good advice of Argos’ renowned seer, Amphiaraus, who instructed him not to join the expedition. “It seems your going was not favored by heaven,” Theseus notes judiciously. “You favored courage instead of discretion.” Adrastus admits to making that grave offense, but nevertheless, he still appeals to Theseus for help in recovering the bodies of the Argive soldiers fallen under Thebes. “Sparta is cruel, her customs variable; the other states are small and weak,” Adrastus makes his case for preferring Athens above all Greek city-states. “Your city alone would be able to undertake this labor; for it turns an eye on misery, and has in you a young and gallant shepherd; for the want of which to lead their hosts, states before now have often perished.”

Barely flattered, after a brief reflection on our prideful human nature, Theseus turns down Adrastus, blaming him for acting rashly and contributing to the ruin of his city “in scorn of the seers and in violent disregard of the gods.” Aware of his position, Adrastus accepts Theseus’ decision and calls upon the Argive women to leave the temple of Demeter. Not ready to do that, they break out into a heart-breaking plea: “Do not, child,” they tell Theseus, “do not let my sons lie there unburied in the land of Cadmus, glad prey for beasts, while you are in your prime, I implore you. See the tear-drop tremble in my eye, as thus I throw myself at your knees to win my children burial.” Aethra is so moved by this appeal that she starts crying and she can’t help but urge her son to change his mind. She reminds him that it is not only his duty to maintain the ancient Greek laws of hospitality and mandatory burial of the dead, but that it is also possible that his refusal to help a suppliant in need might be deemed an act of cowardice by most of the Athenian citizens. Moved by both her arguments and her tears, Theseus reconsiders his decision and proclaims that he will not back off from helping the Argives—but only if the Athenian assembly endorses this decision.

Confident in such an outcome, Theseus exits, followed by Aethra and Adrastus, and leaving the Argive women alone at the temple. In the first stasimon, still burdened by anxiety and fear, they pray that Theseus returns with some good news and that they are granted the chance to see the bodies of their dead sons once again.

Second Episode

After some time, Theseus returns to the temple in the company of his herald. The Athenians have backed his resolve to help the suppliants, so he advises his herald to go to Thebes and ask for the bodies of the dead Argive captains, war being the only other alternative. Before the herald can leave, however, a herald from Thebes arrives at the temple, looking for the Athenian “despot.”

“You have made a false beginning to your speech, stranger, in seeking a despot here,” Theseus replies. “For this city is not ruled by one man, but is free. The people rule in succession year by year, allowing no preference to wealth, but the poor man shares equally with the rich.” The Theban herald is not that charmed by Theseus’ words, suggesting that he might as well have said that his city is ruled by the mob. “You give me here an advantage,” he adds, “as in a game of checkers, for the city from which I come is ruled by one man only.” This retort paves the way for a political battle of wits, during which Theseus and the Theban herald discuss the merits and disadvantages of democracy and tyranny.

Eventually, the discussion evolves from the general into the particular, as Theseus remarks that as powerful as Creon might be in Thebes, he is not the ruler of Athens, nor he is allowed to ask the city to go against its ancient customs and laws. Despite the herald’s warnings, Theseus is now more resolved than ever: he orders his army to prepare for an attack and announces that he is ready to lead them to victory. Soon after, both the herald and Theseus and his men leave for Thebes.

For their second stasimon (and their third choral song), the Argive women split into two semi-choruses and discuss between them their fears of the impending war and their hopes that there is still a chance for them to get to see the dead bodies of their sons without causing unnecessary grief among the Athenian mothers.

Third Episode

A messenger—an Argive just freed from a Theban prison (a former servant of Capaneus, one of the Seven)—arrives from Thebes at the temple of Demeter and brings joyous news to the Argive women: Athens has won the war against Thebes, and Theseus has rescued the bodies of their loved ones. Had he wanted, he could have even stormed the gates of Thebes after forcing the Theban army to retreat inside the city, but even in the midst of the battle he was fully aware of his mission and reminded his zealous army that he had not come to sack the town, but to ask for the bodies of the dead. “Such is the general men should choose,” the messenger praises the balanced character of Theseus, “one who shows his bravery in danger, yet hates the pride of those that in their hour of fortune lose the bliss they might have enjoyed through seeking to scale the ladder's topmost step.”

Wondering why men chose war instead of compromise yet again, Adrastus agrees with the messenger’s assessment of Theseus. In a brief discussion between the two, his respect for Theseus grows even more as he learns from the messenger that Theseus has not only brought the corpses of the five slain captains (all of the dead, excluding Polyneices) but also washed them and prepared them for burial; in addition, he also buried the rest of the Argive soldiers fallen dead during the attack somewhere in the dells of Cithaeron.

“Joy is here and sorrow too,” cry the Argive women in the third stasimon, simultaneously applauding Athens’ success while bemoaning the fact that they are about to see the dead bodies of their loved ones.

Fourth Episode

Their song is not yet finished when Theseus arrives bringing with him five biers containing the corpses of the fallen youths. A heartbreaking lament follows, interrupted after a while by Theseus with a question addressed at Adrastus: “Of what lineage sprang those youths, to shine so bright in courage?” Though usually portrayed as villains in surviving Greek literature, in yet another subversion by Euripides, Adrastus answers the question with a touching eulogy, during which he praises each of the five slain Argive chieftains—Capaneus, Eteoclus, Hippomedon, Parthenopaeus, and Tydeus—as paragons of moderation, integrity, physicality, beauty, and ambition, in that order. Unwilling to allow the Argive mothers to see the decayed bodies of their sons, Theseus announces his intention to burn four of the captains on one funeral pyre and then split the ashes between the suppliant women. The only exception will be Capaneus who, because already stricken by the bolt of Zeus during the battle, will be buried apart as a consecrated corpse.

“The seven noblest sons in Argos once we had,” sing the Argive mothers in the fourth stasimon, observing the lighting of the pyre, “we seven hapless mothers; but now my sons are dead, I have no child, and old age comes to me piteously; neither among the dead nor the living do I count myself, having a lot apart from these…”

Exodos (Exit Song)

Suddenly, the Chorus notices a familiar face standing on a rock overhanging the burning pyre. It is Evadne, Capaneus’ wife and Eteoclus’ sister, dressed in her bridal gown and desolate beyond what words can describe. Her father Iphis follows her closely behind, agitated and perplexed at his daughter’s behavior.

“Now from my home in frantic haste with frenzied mind I rush to you,” Evadne can be heard saying to her dead husband, “seeking to share with you the fire's bright flame and the same tomb, to be rid of my weary life, my suffering, in Hades; yes, for it is the sweetest death to die with those we love, if only fate will sanction it.” Realizing her plan, Iphis attempts to talk her out of it, but his words are to no avail: believing her act to be a victory of female courage, Evadne leaps to her death in the funeral pyre.

Iphis curses his life and wonders why humans are not blessed with the opportunity of living their lives twice over: with his present experience, he says, he would have never decided to have children in the first place, because nothing is as bearable as losing them. As Iphis departs, from the direction of the pyre, a procession enters led by the children of the dead Argives, carrying the ashes of their fathers in urns and surrendering the urns to their grandmothers, the suppliant women.

“Adrastus, and you women sprung from Argos,” cries Theseus, “you see these children bearing in their hands the bodies of their valiant sires whom I redeemed; to you I give these gifts, I and Athens. And you must bear in mind the memory of this favor, marking well the treatment you have had of me.” Adrastus gratefully acknowledges his and Argos’ debt to Athens. This is not enough for the goddess Athena, who unexpectedly appears from above and requests that this pledge be put in writing and addended by Argive promises never to attack Athens and to fight on its side in any future war. In addition, the goddess addresses the children of the slain Argive captains, prophesizing that they will not only avenge their fathers but also grow up to become a theme for the minstrels’ songs in the days to come.

A Brief Analysis

In late 424, the eighth year of the Peloponnesian War, an Athenian army led by Hippocrates managed to seize the temple of Delium (a small town in ancient Boeotia) and turn it into a fortress. However, due to a combination of some innovative warfare devices (possibly a flamethrower) and some exceptionally smart strategizing by the Theban general Pagondas, eventually, the Athenians suffered an unexpected and severe defeat, made even more bitter by the humiliation of having their dead lie unburied for several days after the battle. Could it be that Euripides’ Suppliants was written and produced immediately afterward (423 or 422 BC) as an artistic commentary upon this outcome?

Though many scholars agree with such an interpretation, some tend to think otherwise. These scholars put much more emphasis on the ending of the play, i.e., the oath sworn by Adrastus. Their reasoning goes thus: four years after the Battle of Delium, in 420 BC, Athens signed a four-way alliance with Argos, Elis, and Mantinea. The treaty with Argos was of exceptional importance in view of two facts: 1) Argos had signed a 30-year treaty with Sparta in 451 and, since it didn’t want to wage a war with Athens either, it was virtually neutral until 421 BC; 2) even so, as can be deduced from the contemporary comedies by Aristophanes, Argos was suspected of playing both sides during the 420s. The treaty of 420 BC was supposed to mend this and make Argos an ally of Athens. If written after this event, Suppliants reinforces the importance of this agreement, and in addition to a historical, it also provides a divine justification for its existence. After all, Athena herself explicitly wants the agreement between Adrastus and Theseus “in writing,” and instead of interpreting the treaty as a step toward peace, she sees in its realization a promise for another, more decisive, attack against Thebes, in Euripides’ time, the fiercest Spartan ally.

Either way, it is more than evident that Suppliants is primarily a political play, the interpretation of which depends a lot on its historical background. In this, the play has a lot in common with Children of Heracles, to which it is frequently compared (mostly favorably), both in terms of structure and ideological commitment. Two and a half millennia later, as it often happens with political theater, these two plays seem neither politically nor artistically relevant and are often listed among Euripides’ least appealing plays.

Suppliants Sources

There are many translations of The Suppliants available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read E. P. Coleridge’s translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Arthur S. Way blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Euripides, Seven Against Thebes, Adrastus, Theseus

Suppliants Video

Suppliants Associations

Link/Cite Suppliants Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Suppliants". GreekMythology.com Website, 25 Oct. 2019, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Suppliants/suppliants.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.