Andromache

Andromache by Euripides

First staged sometime between 427 and 423 BC—and probably outside Athens—Andromache is one of Euripides’ earliest surviving tragedies. The play’s prologue is delivered by Andromache, the widow of Troy’s greatest hero Hector, before the temple of Thetis in Thessaly, where she is looking for sanctuary. A few years before the events of the play, we learn from her speech, Andromache had been given as a victory-prize to Neoptolemus—the son of Achilles, her husband’s murderer—and has borne him a son. However, in the meantime, Neoptolemus has married Hermione, who is still childless and, thus, resents Andromache from the bottom of her heart. And now that her husband Neoptolemus is away at Delphi, she sees an opportunity to get rid of both Andromache and her child, with the help of her father Menelaus. The two use her son to lure away Andromache from the altar of Thetis, but just as Menelaus is getting ready to kill her, Peleus, Achilles’ old father, intervenes and scolds Menelaus for his inhumane behavior and cowardice. Somewhat humiliated, Menelaus leaves Thessaly with a promise to come back and discuss the matter of his daughter’s status directly with Neoptolemus. Now that she is left alone and unprotected, it is Hermione’s turn to feel vulnerable and in danger. Fearing that Neoptolemus would never forgive her scheming, she even attempts to commit suicide, but her nurse wrestles the sword out of her hands at the last moment. Just then, Orestes, Hermione’s cousin and former fiancé, suddenly appears (while on his way to Dodona) and, after learning all about her misfortunes, convinces Hermione to take flight with him. As soon as they leave Thessaly, news reaches to Peleus that his grandson, Neoptolemus, has been murdered at Delphi by none other than Orestes. It is Thetis, Peleus’ goddess wife, that comforts him after appearing to him in an epiphany and foretelling both the couple’s reunion and the future destiny of Andromache and her son.

Date and Historical Background

Even though the date of Andromache’s first production is unknown, most scholars agree that it must have been one of the years between 427 and 423 BC. A medieval scholiast, writing on the margin of the 445th verse, suggests that the play wasn’t originally performed at Athens. Modern historians, however, are not so sure.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Andromache, Trojan princess, wife of Hector

• Maid of Andromache

• Molossus, son of Andromache and Neoptolemus (not named in the play)

• Menelaus, king of Sparta, father of Hermione

• Hermione, daughter of Menelaus and wife of Neoptolemus, Achilles’ son

• Nurse of Hermione

• Peleus, father of Achilles and grandfather of Neoptolemus

• Orestes, son of Agamemnon, cousin and former fiancé of Hermione

• Messenger from Delphi

• Thetis, a sea goddess, wife of Peleus, and grandmother of Neoptolemus

• Chorus of Phthian women

Setting

The play is set before the temple of Thetis in Thessaly.

Summary of Andromache

Prologue

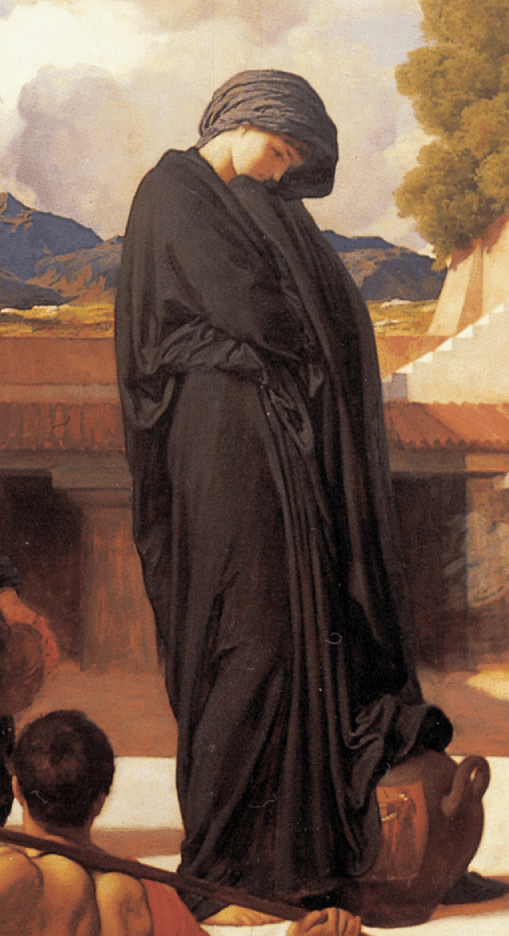

In the tenth year of the Trojan War—the ending of which precedes the events of this play by just a few years—Andromache lost the two most important men in her life: first, her husband Hector, and then, their infant-boy Astyanax. To make matters even worse, Andromache was subsequently taken as a war spoil by none other than Neoptolemus, murderer of her son, and son of her husband’s murderer, Achilles. Though against her will, soon after, she bore her captor a child—though unnamed in the play, later sources call him Molossus—and has thus incurred the wrath of Neoptolemus’ new wife, Hermione, who is still childless.

It is here that Euripides’ tragedy begins: the events described above are related to the audience in the prologue, delivered by Andromache herself, dressed as a suppliant, and while clinging to the altar in front of the temple of Thetis in Thessaly. The reason, she informs us, is that Hermione wants to kill her, not merely because her son is still the sole heir to the throne of Epirus, but also because she believes, for quite some time, that Andromache “with secret poisons… makes her childless and an object of hatred to her husband.” And now that Neoptolemus is absent (he has gone to Delphi), Hermione has seen her chance to do away with Andromache and her son and, to this effect, she has called for the help of her father, Menelaus. Fearing for their lives, Andromache has hidden her son in a secret house and has fled to the temple of Thetis to ask for sanctuary.

Unfortunately—as she is informed by a maid of hers—Menelaus has, in the meantime, discovered Molossus’ whereabouts, and is on his way to kill him. Friendless and alone, Andromache asks her maid to risk requesting the help from Peleus, Achilles’ father. As the maid departs, Andromache falls on her knees and starts cursing her destiny while weeping at the feet of the statue of Thetis.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Andromache’s cries are overheard by a few Phthian women (the Chorus) and they enter the Temple of Thetis to console her. Though somewhat condescending (due to her foreignness), they are mainly sympathetic to Andromache’s destiny and want to help her. Unfortunately, they see no way out for her other than that of submitting to her masters. “Come,” they say to her, “leave the bright seat of the Nereid, recognize that you stand, a slave-woman from another land, on foreign soil where you find none of your friends, o woman most luckless, most wretched.”

First Episode

Just at this moment, Hermione arrives at the temple, as arrogant and as boastful as her queenly status permits her. She points out the difference in standing between her and Andromache—unlike the latter, she is both wealthy and free—and accuses Andromache of planning to throw her out of her own house. “Because of your poisons,” she adds groundlessly, “I am hated by my husband, and my womb is perishing unfruitful because of you.” And she goes even a step further, taunting Andromache for bearing children to the murderers of her kin, Molossus being the grandson of her husband’s killer. “That is the way all barbarians are,” she concludes xenophobically. “Father lies with daughter and son with mother and brother with sister, nearest kin murder each other, and there is no law to stop any of this. Do not introduce such customs into our city.”

In an even lengthier monologue, Andromache replies that it is not a woman’s job to comment upon her husband’s choices, even if given in marriage to a lowly and unworthy man. That is why, she says, she never once scolded Hector for his extramarital affairs, and even breastfed some of his bastards so that she might show him no bitterness. Though she makes it clear that she never intended to become her competitor for the love of Neoptolemus, she doesn’t shy away from blaming Hermione for her unwomanly manners. She even says that it is this, and not drugs, that repel Neoptolemus from her bed. “It is not beauty but good qualities that give joy to husbands,” Andromache declares to Hermione, adding that it would be far more appropriate for her to suffer her marital troubles in silence.

Hermione is not touched by Andromache’s arguments, branding them outdated and barbarian. Seeing that she can’t make Andromache leave her sanctuary neither through words nor by force, she eventually exits the temple, but not before promising to find a way to move Andromache from her seat before Neoptolemus returns—and without any force whatsoever.

In the first stasimon, the Chorus goes back in time and curses Paris for being born and for choosing Aphrodite as the most beautiful goddess. Perhaps, they sing, if one of these events hadn’t happened, perhaps Andromache would have never become a Spartan slave.

Second Episode

If the first episode of Andromache can be described as an agon (contest, struggle) between the titular character and Hermione, the second is as much an agon between Andromache and Hermione’s father, Menelaus, who enters the temple of Thetis quite irreverently, followed by his attendants and leading Andromache’s child by the hand. “If you do not leave and vacate this precinct,” says Menelaus without any delay, “the boy here will be slaughtered in place of you. So, consider this, whether you prefer to die or have this boy killed for the misdeeds you are committing against me and against my daughter.”

“Ah! It is a bitter lottery, a bitter choice between lives, you set before me,” shrieks Andromache movingly, “if I win my life I am in misery, and if I lose it, I am luckless.” After quite a few vain attempts to change his mind, in the end, Andromache decides to surrender. “There,” she says, “I leave the altar and am in your hands, to cut my throat, slay, imprison, or hang me. My child, I, your mother, go to the nether world so that you may not die. And if you escape death, remember the sufferings I, your mother, endured and the death I died, and kissing your father and weeping and embracing him tell him what I have done.”

However, once Andromache is out of the temple, she is in for an unpleasant surprise: it was never a choice, she learns, but a bait, a cruel plot by Hermione and Menelaus to get rid of both mother and son. “Dwellers in Sparta,” shouts Andromache in a bitter anti-Spartan speech, “most hateful of mortals in the eyes of all mankind, wily plotters, masters of the lie, weavers of deadly contrivance, with thoughts that are always devious, rotten, and tortuous, how unjust is the prosperity you enjoy among the Greeks!”

In the second stasimon, the Chorus condemns the quarrels and pain that arise when two women in a single house are rivals for the love of a single man and, after offering a few related examples, suggests that success and peace depend not on the participation and involvement of many, but on a single, smart person being granted full control over a situation.

Third Episode

The third episode starts where the second leaves off—with Andromache and Molossus lamenting their fate and pleading with Menelaus—and presents us with yet another, third agon, this time between Menelaus and Peleus, who, summoned by Andromache’s maid, arrives just in time to prevent Menelaus from killing Andromache.

After hearing out Andromache, Peleus orders Menelaus to loosen her bonds and to release her, at which Menelaus replies that Peleus may have Andromache only over his dead body. Though she was given to Neoptolemus, he adds, it was he who took her captive from Troy. “What?” shouts Peleus irritated. “How do you merit inclusion among the men, you utter coward?” And then Peleus goes on a tirade against Menelaus, during which he blames the Spartan king for starting a disastrous war over his unfaithful and worthless wife and even suggests that it was him who incited Agamemnon to sacrifice Iphigenia. Moreover, the weakling that he is, he has even accepted Helen back to his house, instead of killing her under Troy for the traitor that she was and for all the exemplary lives her shameful flight cost Greece.

Menelaus says that the flight was not Helen’s decision, to start with (it was the will of the gods), but that the war which it incited has helped Greece make progress in all aspects of life. As for his resolve to kill Andromache, Menelaus defends it by pointing out that, in the absence of other children, it’d be Molossus, an Asian and a barbarian, who’d rule Peleus in the future. That way, to some extent, the Trojans would win a battle against the Greeks—after losing the war.

Peleus is not convinced by Menelaus’ arguments and frees Andromache and Molossus, implying that if the Spartan king has anything against this act, he should take it with his son-in-law Neoptolemus. Menelaus, surprisingly, backs off: “Since I have come to Phthia against my will,” he says, “I shall not do anything demeaning nor will I have it done to me.” Even more surprisingly, he suddenly remembers a military expedition he is supposed to embark on and leaves, promising to return once Neoptolemus is back.

In the third stasimon, the Chorus pays tribute to Peleus’ admirable life, going all the way back to his part in the voyage of the Argonauts. Additionally—and somewhat unrelatedly—it also offers generalized praises of noble birth, wealth and courage.

Fourth Episode

Now that Menelaus’ plan has backfired—not only are Andromache and her child safe now, but they have found a protector in the elderly king as well—Hermione is suddenly in a very inconvenient position. As we are informed by her nurse at the beginning of the fourth episode, Hermione is even thinking about killing herself out of fear from Neoptolemus’ wrath once he finds out about her plot. Very soon it becomes clear that this is not an exaggeration: shouts are heard from inside the royal palace, and it is only down to the nurse’s alertness that Hermione is eventually saved from death. However, she is inconsolable: “You have abandoned me, father, abandoned me, all alone on the shore with no sea-going oar!” she cries. “He will kill me, kill me! No more shall I dwell in this bridal house of mine!”

Fortunately, just then—passing through Phthia, while on his journey toward the oracle of Zeus at Dodona—Orestes arrives at Hermione’s house with an intention to see if his relative (Hermione is Orestes’ cousin) and former fiancée (she had once been betrothed to him) is “alive and enjoying good fortune.” Upon learning of Hermione’s situation, Orestes offers her an unexpected way out: “Since your fortunes are in ruins and you have fallen into this calamity and are helpless, let me take you home and give you into the hand of your father… For you were mine, to begin with.” At first, Hermione doesn’t want to run away out of fear of Neoptolemus’ revenge, but Orestes calms her down, revealing that a death trap awaits Neoptolemus in Delphi and that he might as well be dead already.

As the two flee, in the fourth stasimon, the Chorus wonders what kind of a god might Apollo be when he has not only presided over Orestes’ murder of his mother but he has also allowed Troy (the city he had once built) to be utterly destroyed, its inhabitants scattered and suffering all over Greece.

Exodos (Exit Song)

The rumors of Hermione’s flight having reached his ears, Peleus returns once again before the temple of Thetis to ask if they are true. Just as the Chorus confirms them, a messenger arrives bringing terrible news: Neoptolemus is dead, killed treacherously and impiously while making sacrifices at the temple of Delphi, in an ambush prepared by none other than Orestes. Peleus is left heartbroken and inconsolable and, in his grief, harshly condemns Apollo for taking away from him both Achilles and Neoptolemus.

Just as Peleus says goodbye to his scepter and his divine wife—possibly suggesting that he is preparing to kill himself—suddenly, an apparition appears above him: it is Thetis, his wife, come from the house of Nereus to counsel the aged king.

She comforts him by telling him that though both Achilles and Neoptolemus are dead, his grandson Molossus will bear numerous descendants who will rule over Molossia and live their lives in prosperity. She also instructs him to bury Neoptolemus near the altar at Delphi, so that his grave may testify to his violent death and the character of his murderers. Finally, she tells him that—in gratitude for being always kind to her—she will make him a god once his time has come, deathless and exempt from decay. “And then you shall dwell with me in the house of Nereus,” she says lovingly, “god with goddess, for all time to come.”

“A god finds a way to achieve the unexpected,” concludes the Chorus as Thetis disappears and Peleus prepares to leave for Delphi, as per her instructions.

A Brief Analysis

One of Euripides’ poorest theatrical achievements—both in terms of structure and overall effect—Andromache is (in Aristotelian terms) a highly episodic play, in that, rather than condensing, it expands the action, and rather than limiting the number of important characters to a protagonist and one or two secondary main characters, it essentially works as a series of subplots, each featuring a different despairing individual.

Only its first part justifies the title: Andromache seems the focus of the play just until Peleus saves her from being murdered by Menelaus. Afterward, she literally disappears from the tragedy, and the focus shifts to the grieving Hermione. She too is saved at the last moment—and this time by a highly unexpected guest, Orestes—and, by fleeing with him, she takes her issues away from the play as well. It is now Peleus’ turn to become the grieving protagonist and stretch the play a bit more. This seemingly unending and culmination-less circle of misery is abruptly discontinued by a rare guest in Euripides’ tragedies—a benevolent god—framed within a common and oft-criticized Euripidean technique: deus ex machina.

Because of all of the above, not a few scholars try to salvage the unity of Andromache by thinking of Neoptolemus as its main character. And indeed, it is his absence (at first temporary and by the end of the play, everlasting) that serves as the engine of the play, constantly inspiring and spurring the actions of all other characters, be they the three main ones (Andromache, Hermione and Peleus) or the two secondary ones (Menelaus and Orestes).

First produced in the early years of the Peloponnesian War, Andromache is a political play as well. Contrasted against the heroism of the Andromache (a Trojan princess) is the odiousness of the Spartan trio of characters (Menelaus, Hermione and Orestes), and sometimes Euripides’ attempt to make this contrast more impressive goes so far that it seems unmotivated—or, at least, not justified—by the relationship between the characters of the play. For example, it is difficult to explain why Menelaus backs away from murdering Andromache even despite Peleus’ words and, moreover, why he remembers just then a military duty of his. Though probably one of the few ways for Euripides to justify Menelaus leaving his daughter unprotected behind him, the latter seems neither plausible nor adequate—even for such one-dimensional and poorly developed character as Menelaus.

Andromache Sources

There are many translations of Andromache available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read David Kovacs’ translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Arthur S. Way blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Euripides, Neoptolemus, Menelaus, Andromache

Andromache Video

Andromache Associations

Link/Cite Andromache Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Andromache". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Andromache/andromache.html. Accessed 17 April 2024.