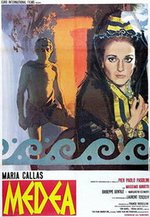

Medea

Medea by Euripides

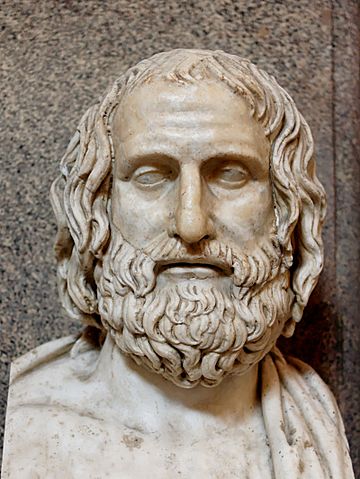

First performed in 431 BC and not well received by its original audience, Euripides’ Medea is nowadays considered one of the best, most controversial and most haunting Ancient Greek tragedies.

It is set in Corinth, where, long before the beginning of the play, Jason and Medea have arrived as exiles. Even though Medea (a former princess of Colchis) has sacrificed both her home and her family for Jason, he, as we are informed by a Nurse in the Prologue, has decided to marry the daughter of Creon, the King of Corinth. It is Creon who sets in motion the events of the play, banishing Medea and her two children by Jason immediately from his kingdom.

The Nurse, conscious of Medea’s terrible temper, is afraid about what she may do in retaliation and relays her worries to the Tutor of the children who fully understands and backs her fears. However, when Medea first appears on stage, visibly shaken by the extent of her misfortunes, she attracts a lot of sympathy and compassion from the Chorus of Corinthian women who go so far to even justify a possible murder of Jason. Creon doesn’t share this feeling and reminds Medea that she is banished and must leave Corinth as soon as possible. She solicits the King to allow her to remain another day to find some solution for her children, and Creon grants Medea her wish. As soon as he leaves, Jason arrives to give justification for his actions, but it is to no avail—neither Medea nor the Corinthian women believe him or the sincerity of his intentions. Soon after, through a happy and somewhat implausible accident, Medea happens upon Aegeus, the King of Athens, and arranges a sanctuary with him. Then she declares her real intentions: to kill Glauce, Jason’s new bride, and then to slay her own two children. Not wasting a second of her time, she calls for Jason and tearfully apologizes to him about everything, begging him to accept some golden robes and a coronet as a gift for Glauce, one that may make Creon change his mind about exiling her. It is Medea’s children who deliver the gift to the princess, not knowing that the robes are poisoned. Soon after they return, a messenger announces the agonizing death of Glauce, as well as that of her father who poisoned himself by clutching her daughter tightly in an attempt to help her. It is not enough: to hurt Jason as much as he had hurt her, Medea goes inside her house and kills her children, whose cries are heard off-stage. Jason rushes into the scene to confront Medea about the deaths of Creon and Glauce only to find about the even greater tragedy and see his former wife flying off in the chariot of the Sun, the lifeless bodies of their children in it.

Date and Historical Background

From an ancient hypothesis (“introduction,” “argument”) we know that Medea was part of a tetralogy (alongside Philoctetes, Dictys and the satyr play Harvesters) first performed during the archonship of Pythodôrus, in the first year of the 87th Olympiad (431 BC). However, despite Medea’s popularity today, Euripides not only didn’t win, but he came in last, behind Sophocles, and Euphorion (Aeschylus’ son), who won that year’s competition (possibly by (re)staging his father’s Prometheus Bound).

Characters and Setting

Characters

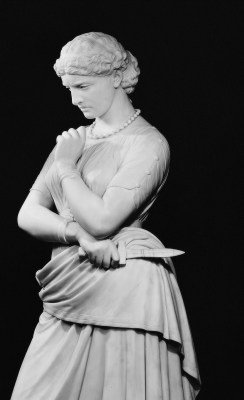

• Medea, daughter of King Aeetes of Colchis

• Jason, the leader of the Argonaut expedition; nephew of Pelias, King of Iolcus in Thessaly

• Creon, King of Corinth

• Aegeus, King of Athens

• Nurse of Medea

• Children of Jason and Medea

• Tutor of the children

• Messenger

• Chorus of Corinthian women

Setting

Corinth, in front of Medea’s house. A road to the right leads to the royal palace (of Creon), and a road to the left leads to the harbor.

Summary of Medea

Prologue

At the beginning of the play, Medea’s Nurse walks out of her house in Corinth and, in a long monologue, expresses her impossible wish for the past to have never happened. Maybe, she vainly comforts herself, if Jason hadn’t sailed away to Colchis, he would have never fallen for Medea, and she would have never wound up being as hurt as she is now. “Now all is enmity,” says the Nurse, “and love's bonds are diseased,” referring to the fact that Jason has just recently abandoned Medea and his own children to marry the daughter of Creon, the ruler of Corinth. The Nurse is doubly concerned: not only because Medea is “wasting away in tears all the time ever since she learned that she was wronged by her husband,” but also because she “has a terrible temper and will not put up with bad treatment.” Fearing that Medea may end up killing someone—either herself or Jason—the Nurse dubs her a “dangerous” woman.

It is at this moment that Jason and Medea’s two sons, escorted by their Tutor, appear. The Tutor expresses his concerns over Medea’s state as well, adding that it may get worse once she hears “her latest trouble.” Namely, he has overheard gossip that Creon, fearing some kind of retribution on her part, has banished Medea and her children from Corinth. As the Nurse curses Jason, Medea’s cries and bellows can be heard from within the house. The Tutor and the children go inside, and, soon after, a group of Corinthian women (the Chorus) arrives before Medea’s home.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

“I have heard the voice, I have heard the cry, of the unhappy woman of Colchis: is she not yet soothed?” the Corinthian women ask the Nurse, obliging her to talk Medea into coming out of her house so that they can comfort her. The Nurse agrees to grant the Corinthian women this request but expresses doubts whether she would be successful in persuading her mistress.

Medea’s cries can be heard throughout this discussion. She invokes Themis and Artemis, and wishes the worst for Jason and her new bride, cursing herself for giving up so much to follow love. “O father, o my native city, from you I departed in shame,” shrieks Medea, reminding us of the fact that, in addition to helping Jason feat after feat with her magic, she even killed and dismembered her own brother, Absyrtus, to help him escape from the wrath of her father, Aeetes.

First Episode

Medea comes out of the house and, soon after greeting the Corinthian women, bursts into a famous monologue, which, even today, sounds radically feminist. “Of all creatures that have breath and sensation, we women are the most unfortunate,” she says, lamenting the fact that women are forced by societal norms to marry, which, for them, boils down to buying, at “an exorbitant price,” a master of their bodies. And everything depends upon this choice, for, divorce is not an option women have: if they realize they don’t like the man they marry, women are better off dead according to Medea, because otherwise, they’ll spend their lives serving someone they hate. “A man,” Medea concludes defiantly, “whenever he is annoyed with the company of those in the house, goes elsewhere and thus rids his soul of its boredom. But we must fix our gaze on one person only. Men say that we live a life free from danger at home while they fight with the spear. How wrong they are! I would rather stand three times with a shield in battle than give birth once.”

Surprisingly, not only the Chorus understands Medea’s rage, but also approves of her radical beliefs, going so far to even say that she has all to right “to punish” her unfaithful husband. The opinion, of course, is not shared by King Creon who appears on stage at about this moment. “I order you to leave this land and go into exile, taking your two children with you, and instantly,” he delivers his decree upon seeing Medea, justifying his decision as a necessary precaution and as a direct consequence of his fear that Medea might do something to his daughter.

Medea allays Jason’s fears, flattering his line of thinking, but downplaying her anger, which she claims is reserved for Jason only. She eventually even agrees to leave Corinth but pleads for one day's delay so that she could prepare for her exile, and find a safe place for her two children. Eventually, Creon acquiesces and leaves. Left alone with the Chorus, Medea reveals it was all a ploy: “Do you think I would ever have fawned on this man unless I stood to gain, unless I were plotting?” she says ominously, before uncovering her plan—to kill Creon, Jason, and his new wife Glauce by poison. Only one thing is stopping her from doing that right away: no city would receive her and her children after such a deed, so she would have no place to run away to.

In the first stasimon, the Chorus bemoans the lack of justice in this world and the undeserved fate of Medea who, they sing, is basically alone on this world, being a stranger to her country, her family, her husband, and, now, even the city of her exile.

Second Episode

Enters Jason and immediately starts an argument with Medea, pointing to her “fierce temper” and “foolish talk” as the reasons for her exile. Medea, in return, blames him for “shamelessness”: how dares he accusing her of anything, when it is because of him that she has no more a homeland or a family to go to? She reminds him of everything she has done for him during his journeys, but Jason downplays both her role as a helper and her love for him, dismissing the latter as just another one of Eros’ caprices. He even tries to convince Medea that his decision to marry a princess was for the sake of their children: if he hadn’t married Glauce, they would have remained poor and “everyone goes out of his way to avoid a penniless friend.” Neither Medea nor the Corinthian women can believe their ears: “even though it may be imprudent to say so,” says the Chorus, “in abandoning your wife, you are not doing right.” Tired of arguing, Jason offers Medea some money for her exile, and after she refuses, leaves.

In the second stasimon, the Corinthian women ask from Aphrodite that they find only moderation and peace in their marriages. They also pray to never be exiled from their homeland, and that people like Jason, who betray their own family, be properly punished by the gods.

Third Episode

In the third episode of the play, Medea happens upon Aegeus, the king of Athens, who has come to Corinth to find out from an oracle why he can’t have any children. Medea promises him that she will cure his sterility through sorcery if he gives her sanctuary in return. After hearing all about Jason’s cruel betrayal, Aegeus swears by Gaea and Helios to do so: “I will not consent to take you from this land,” he says to Medea, “but if you manage by yourself to come to my house, you may stay there in safety, and I will never give you up to anyone.”

Now that she has found a sanctuary, Medea finalizes her plan. She announces her intent to trick Jason into accepting gifts send from her—“a finely-woven gown and a diadem of beaten gold”—to Glauce. However, she reveals to the Chorus that she will poison both of these gifts beforehand so that if Glauce puts them on, she (and everyone who touches her) should die a painful death. For the first time in the play, she also announces an additional, even more gruesome aspect of her revenge: to kill her children, that way utterly annihilating Jason’s house.

In the third stasimon, the Chorus urges her to not do this, but Medea is, nevertheless, resolute and has no intention of backing away.

Fourth Episode

In the second of their three encounters during the play, Jason comes before Medea’s house to ask her what she wants from him. “I beg you to forgive what I said,” she says to his utter surprise, before explaining away both her anger and her tears as her immediate and irrational response, common and natural to all women. In the presence of their sons—whom she calls herself to witness the mending of their parents’ relationship—Medea agrees to go to exile but begs her former husband to say a word or two in their favor. To solicit some sympathy in the princess and her father, Medea says that she wants to gift Glauce with a gown and a diadem, passed down to her from none other than her grandfather, Helios. Despite Jason’s objections (“Do you think the royal house has need of gowns or gold?”) and his paternalistic conviction that Glauce will value his wishes “more highly than wealth,” Medea sends her children (together with their Tutor) to deliver the gifts to the princess.

In the fourth stasimon, the Chorus sings of the impending death of both Glauce and Medea’s children, lamenting their death and cursing Jason for sending his children and his new wife to death unwittingly and through betrayal.

Fifth Episode

Soon after, the Tutor returns from the palace with some happy news: “My lady,” he says to Medea, “your sons here have been reprieved from exile, and the princess has been pleased to take the gifts into her hands.” Even though Medea’s immediate reaction confuses the Tutor—she is sad rather than happy—he enters the house soon after relaying the news, leaving Medea alone with her children.

What follows is an exceptional soliloquy by Medea, which skillfully portrays her doubts and hesitations, and during which she changes her mind several times. True, nothing will hurt Jason as much as the murder of her children, but the act would be unbearable to her as well. Since going in exile and leaving her sons in Corinth is almost as agonizing, at one point, Medea is even ready to take her children with her and leave immediately. However, eventually, she sees how complicated this act would be now, and can’t bear the thought of making Jason thus a twofold favor. “I shall never leave my children for my enemies to outrage,” she exclaims a moment before taking the children into the house. “They must die in any case. And since they must, the one who gave them birth shall kill them.”

In the fifth stasimon, the Chorus blesses all childless parents, because they don’t have to worry constantly about their happiness or endure the insufferable pain of watching them leave to Hades before their time.

Sixth Episode

A messenger from the palace arrives before Medea’s house and brings the news Medea has been waiting for some time. Both Glauce and Creon are dead, the former due to the immediate impact of Medea’s gifts, and her father as a result of embracing the dead Glauce. The messenger warns Medea that her punishment is coming, but the Chorus is far more sympathetic: “It seems that fate is this day fastening calamity on Jason, and with justice.”

As Medea enters the house to kill her children, the Chorus begs Gaea and Helios to do something to stop her. It is to no avail—their song is interrupted by the heartbreaking cries of Medea’s sons: “Oh, what shall I do? How can I escape my mother's hands?... We are now close to the snare of the sword.”

Exodos (Exit Song)

Jason comes for the third and final time before Medea’s house, this time with an intention to punish her for the death of Creon and Glauce, and a resolution to save his children from the wrath of his wife’s family. “Poor Jason,” says the Chorus Leader, “you have no idea how far gone you are in misfortune. Else you would not have spoken these words… Your children are dead, killed by their mother's hand.”

Soon after, Medea appears above the houses in a winged chariot, the bodies of her dead children next to her. Jason curses the day of their meeting and the monstrous, barbaric nature of Medea, but she remains untouched by the offenses: “Call me a she-lion, then, if you like, and Scylla, dweller on the Tuscan cliff,” she says, “for I have touched your heart in the vital spot.”

Jason demands the bodies of his sons, but Medea is adamant that he doesn’t deserve them since he had refused them while they were alive. She even refuses to let him touch their “tender flesh” and flies off triumphantly to Athens. Jason and the Chorus remain behind, wondering what kind of gods or demons live on Olympus to allow this kind of outcome.

A Brief Analysis

Curiously, with the exception of Alcestis and Cyclops—neither of which are tragedies—Medea is the only surviving play by Euripides which requires no more than two actors. This simple structure, however, has some stunning results: apart from the prologue, all scenes involve Medea and someone else. As Storey and Allan observe, this allows the readers/viewers to observe her in all of her fluctuating complexity: she is rational with the Chorus, flattering to Creon, angry with Jason, wise with Aegeus, hesitant and mentally unstable in her soliloquy, and as vengeful as an offended goddess at the conclusion of the play. Considering the fact that Euripides is often fond of employing abrupt resolutions to the unsolvable problems in his plays, it is fascinating that here he opted to use one of his favorite theatrical devices (deus ex machina) for precisely the opposite effect. Namely, even though Medea is flying off in a chariot at the end of the tragedy, the act leaves so many open questions that it is difficult to speak of any kind of resolution. Medea has certainly crossed a line in her revenge, but should we empathize with Jason now? How about with Creon or Glauce? If Medea hadn’t murdered her children, would her revenge be complete or, as the Chorus itself suggests at one place, even just? How would we have interpreted the play if such an act of revenge was enacted by a male character? Finally, as the concluding stanza implies, what kind of gods are in charge of the world if such things as the ones depicted in Medea are possible? How absent are they from our world? And if present, who are they supposed to punish and with what kind of punishment now? Few ancient plays are as powerful and as traumatic as Euripides’ Medea; and few—if any—tragic characters have proven more haunting and more memorable than its main protagonist.

Medea Sources

There are many translations of Medea available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read David Kovacs’ translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Gilbert Murray’s rhyming verse adaptation here.

See Also: Euripides, Medea, Jason, Argonauts

Medea Video

Link/Cite Medea Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Medea". GreekMythology.com Website, 08 Mar. 2022, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Medea/medea.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.