Hecuba

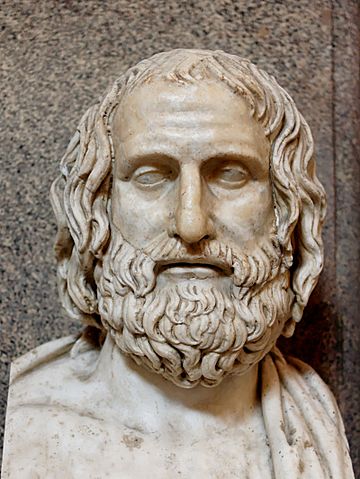

Hecuba by Euripides

Written in or around 424 BC, Hecuba is one of a few plays by Euripides that treat the immediate aftermath of the Trojan War. Hecuba, until recently Troy’s queen and now a Greek slave, is being carried off to her new homeland by her captors. However, due to the ghost of Achilles appearing above his tomb and demanding to be pleased with sacrifice, the Greek navy is forced to make a stop in the Polymestor-ruled land of Thrace. There, Hecuba’s youngest son, Polydorus, had been sent for safety during the Trojan War, but, unknown to his mother, he was murdered by Polymestor as soon as the king of Thrace had received the news of Troy’s fall. It is the ghost of Polydorus who shares a large part of this story in the play’s prologue. Not long after he vanishes, a chorus of captive Trojan women inform Hecuba that the life of her youngest daughter, Polyxena, is in grave danger: the Greeks intend to sacrifice her as an offering to the dead Achilles, per his ghost’s request. Hecuba implores Odysseus to spare his daughter’s life, but Odysseus is deaf to her pleas. Polyxena intervenes to say, surprisingly, that she needs nobody to fight for her life because she’d rather die a free woman than live the life of a slave. Polyxena’s courageous death is narrated in a long monologue by Talthybius, the herald of Agamemnon. Barely he has finished extolling praises upon her for her noble demeanor when the dead body of Polydorus is discovered by a servant, floating in the sea. Out of her mind with grief, Hecuba asks Agamemnon to allow her to avenge the death of her son. Agamemnon neither agrees but nor refuses either, and soon enough, Polymestor and his two sons are lured into Hecuba’s tent. There, Polymestor’s sons are murdered, and he himself is blinded by Hecuba. A trial follows with Agamemnon presiding as the judge and ruling in favor of Hecuba: her act, he says, was not only an act of revenge but also an act of justice. In rage, Polymestor curses both Agamemnon and Hecuba, predicting the imminent death of both.

Date and Historical Background

Even though there is no agreement as to the definite date of Hecuba, on the basis of metrical evidence and Aristophanic parody—in addition to one or two probable allusions to historical events (such as the re-establishment of the Delian festival)—almost all scholars place Hecuba's first production in the mid-420s, most commonly in 424 BC.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• The Ghost of Polydorus, son of Priam and Hecuba

• Hecuba, Priam’s wife, Troy’s queen, the mother of Polydorus and Polyxena

• Polyxena, the youngest daughter of Priam and Hecuba

• Odysseus, King of Ithaca

• Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, commander of the Greeks under Troy

• Talthybius, herald of King Agamemnon

• Polymestor, King of Eastern Thrace

• Handmaid of Hecuba

• Chorus of captive Trojan women

Setting

The play is set before the tent of Agamemnon, in the camp of the Greeks on the coast of Chersonese, a region of Thrace opposite to Troy.

Summary of Hecuba

Prologue

In the prologue to Hecuba, the ghost of Polydorus—Priam and Hecuba’s youngest son—comes out of the grave to tell his story. He reveals how, sometime after the beginning of the Trojan War, he was sent by his father Priam to the court of his guest-friend, King Polymestor of Thrace, with gifts of gold. Priam’s reasons for this were threefold: 1) Polydorus was too young to fight; 2) Priam didn’t want the Trojan War to put an end to his royal line; and 3) he wanted to make sure, if Troy’s walls should fall, that his surviving children would have all the necessary means to live a noble life.

Unfortunately, as soon as the news about Troy’s fall reached Thrace—unsurprisingly, for the sake of the young man’s gold—Polymestor killed Polydorus, his helpless guest, and cast him into the sea, leaving the boy’s body to drift with the waves, unwept and unburied. Polydorus, however, intends to change this by appearing before the feet of his mother’s maid: he has begged the gods for this and they have appealed to his prayers.

But how has Hecuba, Polydorus’ mother, and her servants ended up in Thrace? Well, that’s yet another sad story. See, Hecuba has just recently been captured by the Greeks at Troy and boarded as a slave on one of their ships. However, the Greek navy has just recently been stopped at the shores of Thrace by the appearance of the ghost of the freshly murdered Achilles. As Polydorus informs us, Achilles has proclaimed not to allow the Greeks to move forward, unless he receives a victory spoil for his efforts under Troy. The reward he has set his eyes upon is none other than Polyxena, Polydorus’ youngest sister. “So will my mother see two children dead at once, me and that ill-fated maid,” lets us know Polydorus at the end of his speech, bemoaning the fate of Hecuba, “as sad as once it was blessed.”

As if summoned by the ghost of Polydorus, Hecuba arrives onstage, coming out of the tent of Agamemnon, agitated and distraught. She has been visited by a vision in a dream, she says—in fact, it is the ghost of Polydorus that she has hazily observed—and she now fears for the lives of her youngest son and daughter. “Some fresh disaster is in store, a new strain of sorrow will be added to our woe,” she cries.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Barely has Hecuba finished praying to the gods that she might be wrong, a Chorus of captive Trojan women enters with some terrible news: after being scolded by the gold-armored ghost of Achilles for not appeasing him with a victory spoil, the Greeks have decided to sacrifice Hecuba’s daughter Polyxena at his grave. Even though initially the soldiers were divided in their views, in the end, Odysseus, the “shifty, smooth-mouthed liar… whose tongue is always at the service of the mob,” prevailed and managed to persuade the army to take this course of action. He’s on his way now to tear Polyxena from Hecuba’s aged arms. “Go to the temples, go to the altars, at Agamemnon's knees sit as a suppliant!” the Trojan women advise Hecuba; it’s either that, they add, or eternal sorrow.

First Episode

“Ah, Trojan maids! bringers of evil tidings! messengers of woe!” cries Hecuba upon hearing the news. “You have made an end, an utter end of me; life on earth has no more charm for me.” Bemoaning the fact that she has neither a family nor a god to stand by her in these dreadful moments, Hecuba does the only thing she can: she calls for her daughter to tell her at once about the “hideous rumor.”

Polyxena appears soon after and is almost immediately told that the Greeks plan to sacrifice her to Achilles. Noble beyond her age and magnanimous beyond what’s humanly possible, she starts lamenting the fate of her mother: “For your unhappiness I weep with plaintive wail, mother,” she says, “but for my own life, its ruin and its outrage, never a tear I shed; no, death has become to me a happier lot than life.”

It is at this moment that Odysseus arrives to fetch Polyxena. Hecuba tries to stop him by reminding him that he owes her a favor. Namely, early in the Trojan War, she chose not to reveal Odysseus’ identity, even though Helen had recognized him under his mask while on a spy mission and trusted her with this knowledge. “On your own confession,” Hecuba tells Odysseus, “you fell at my feet and embraced my hand and aged cheek; I, in my turn now, do the same to you, and claim the favor then bestowed; and I implore you, do not tear my child from my arms or slay her; there are dead enough.”

Odysseus, however, is not touched by Hecuba’s pleas. He says that though he is prepared to save Hecuba’s life at any time, he is not at all interested in debating Polyxena’s. Denying Achilles what’s due to him would inevitably cause unrest among the troops, leading his soldiers to question whether they should fight at all for Greece seeing that Greece doesn’t honor its bravest dead.

Seeing no way out, Hecuba begs her daughter to “throw herself pitiably at Odysseus’ knees and try to move him,” but, instead, Polyxena does the very opposite: she asks Odysseus to lead her away immediately and do his worst, since she’d much rather die a free woman than endure a life of slavery forcefully dedicated to the base needs of some savage foreign master. In one last attempt, Hecuba tries to prevent the inevitable by offering her own life in place of her daughter’s, but to no avail—neither Polyxena nor Odysseus accept her proposal.

As the Greek hero leads her daughter away and Hecuba sinks fainting to the ground, in the play’s first stasimon, the Trojan women lament their own fate, cursing the sea winds that will very soon take them to Greece where they are bound to spend their lives as wretched slaves.

Second Episode

At the beginning of the second episode, Agamemnon’s herald Talthybius arrives before his master’s tent to tell Hecuba the “sad tale” of Polyxena's final hours. The young maiden, we learn from his speech, refused to be held firmly by two Greek warriors (as was only customary in sacrifices), and, instead, tore her robe from shoulder to waist on her own. She then defiantly invited her killer, Neoptolemus, to strike her in her bosom or her neck, and still found enough strength in her dying body to fall gracefully and die a death befitting a princess.

Grief-stricken and devastated, Hecuba orders Talthybius to immediately proclaim to the Greeks that they don’t touch her daughter’s body, and simultaneously sends her “aged handmaid” to fetch water from the sea so that she can, for the last time, ritually wash her child, “an unwed bride, a ravished virgin, and lay her out, as she deserves.”

In the second stasimon, the Trojan women remind us that Polyxena is just the last of countless innocent victims of a vicious cycle of war, death and revenge, started innocuously on Mount Ida many years before by the rash and ill-informed judgment of the Trojan prince, Paris.

Third Episode

Hecuba’s handmaid returns from the sea, but, unfortunately, she brings not only the promised pitcher filled with saltwater but also two things much more ominous: a dead body and some terrible news. Unwilling to utter them, she uncovers the corpse she’d found washed ashore, and Hecuba recognizes under the shroud Polydorus, the only one of her children she thought safe. “O dreadful crime!” shouts she, instantly realizing that Polymestor has probably killed her son for his gold. “O deed without a name! beyond wonder! impious! intolerable! Where are the laws between guest and host?”

Hecuba is in the midst of her lament when Agamemnon arrives with the intention of scolding her for delaying the burial of Polyxena. After deliberating a bit whether she should talk to him or not, Hecuba realizes that it is only with his aid that she should be able to get Polymestor back, so she implores him to grant her “vengeance on the wicked.” Agamemnon is confused at first, but Hecuba shows him the dead body of Polydorus and recounts her son’s full story. She even reminds him that the two share something in common—Hecuba’s daughter Cassandra is now Agamemnon’s lover—and that by doing her a service, he will also do a service to two kinsmen of his bride's. Agamemnon, however, is reluctant to grant Hecuba’s wish. After all, he says, as far as his army is concerned, since the dead (Polydorus) was their foe, his murderer (Polymestor) is their friend, and helping Hecuba get rid of the latter would seem as if something done for Cassandra’s sake.

In that case, Hecuba says, the only thing she asks from Agamemnon is to not intervene and stop her in her planned revenge. Agamemnon grants her that, for two reasons. First of all, even if he had wanted to get involved, he wouldn’t have been able to, because there are no winds and the Greek fleet is stuck in Thrace. Secondly, he doesn’t believe that women—of whom he has “mean opinion”—are able to overpower men.

Agamemnon departs, Hecuba withdraws in her tent, and the Chorus of Trojan women, in the third stasimon, mournfully remembers the night of the sack of Troy and curses Paris and Helen for their—and everybody’s—misfortune.

Exodos (Exit Song)

Followed by his two sons and a couple of guards, Polymestor arrives before the tent of Agamemnon and asks Hecuba what need she might have of him (apparently, Hecuba had sent for him in the meantime). “I wish to tell you and your children a private matter of my own,” she replies, asking him to bid his attendants withdraw from Agamemnon’s tent. Now that she is alone with Polymestor and his children, Hecuba asks him whether Polydorus is safe, at which Polymestor answers in the affirmative. Feigning gratitude, Hecuba reveals the supposedly real reason behind her call: she wanted to tell Polymestor the secret hiding place of the remaining treasures of Troy, provided that he promises to pass this knowledge on to Polydorus. Polymestor agrees not only to this but also to follow Hecuba to a secret Trojan hut inside the Greek station (located offstage) where she claims to have managed to hide some treasures brought from Troy. Inside, however, with the help of her slave women, Hecuba blinds Polymestor and kills his sons.

“O horror! I am blinded of the light of my eyes, ah me! O horror! horror! my children! O the cruel blow,” shouts Polymestor, comparing his state to that of a “wild four-footed beast.” Hearing the cry, Agamemnon rushes to the scene and entreats to find out what has happened. The two tell their stories. Polymestor claims that his murder of Polydorus was motivated by his allegiance with the Greeks, and describes Hecuba’s act as a truly contemptible act, befitting only the vilest of creatures. Hecuba angrily refutes him: “it was the gold that slew my son, and your greedy spirit,” she says, asking him why, if he had loved the Greeks so much, he hesitated to kill Polydorus when Troy’s walls stood still intact, and why has he still not gifted Agamemnon and his army Polydorus’ gold?

Though reluctant “to be judge in stranger’s troubles,” Agamemnon is convinced by Hecuba’s arguments and sets the matter in her favor. Polymestor, raging in pain and grief, curses Hecuba and Agamemnon and foretells their doom, sharing with them the divinations of Dionysus, the Thracian prophet. Hecuba, he says, will one day be transformed into “a dog with bloodshot gaze,” and will subsequently be buried under a tomb bearing the inscription: “The hapless hound's grave.” Moreover, her daughter Cassandra is destined to be killed by Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife, who will then slay her husband as well.

Expectedly, neither Hecuba nor Agamemnon are happy with these predictions, so the Greek commander orders that Polymestor be punished for his wicked words by being cast upon some desert island. At that very moment, Agamemnon senses a breeze rising above the sea and leaves to inform the fleet. His parting words sound both ironic and ominous: “May we reach our country well and find all well at home, released from troubles here!” The chorus is, understandably, less jubilant and more realistic: “Away to the harbor and the tents, my friends, to prove the toils of slavery! for such is fate's relentless command.”

A Brief Analysis

Though episodic to its detriment as a whole, Hecuba is neither short of memorable moments nor as structurally flawed as Andromache, its immediate predecessor in the chronology of Euripides’ plays. True, once more, the plot of the tragedy falls into clearly discernible parts—in this case, two: the sacrificial death of Polyxena and Hecuba’s revenge on Polymestor—but these are held together by the constant presence of a single, domineering and nuancedly portrayed character whose gradual demise into madness and wickedness is so vividly rendered that it is difficult not to leave the play’s readers/viewers with a bitter taste in their mouths.

Moreover, Hecuba’s transformation from a victim to a villain occurs against a background of three masterfully guided discussions, each of which is between her and a man, and each of which reveals a subversive portrait of three archetypal heroes.

The first of these discussions is between Hecuba and Odysseus and it concerns the life of Polyxena. Even though Hecuba eventually loses the debate, Odysseus seems to lose something much more important: our respect. Namely, even though we learn that Hecuba has saved his life once, he is all but indifferent to her pleas and motherly love, while being ill-mannered and disrespectful in his behavior toward her.

The second debate is between Hecuba and Agamemnon over her right to avenge the death of Polydorus. It is difficult to consider Hecuba the winner of the debate—its final decision is somewhat arguable—but it is easy to see why Agamemnon is not: having just led an army to a famous victory, faced with his opponent’s enslaved queen, the Greek commander-in-chief seems a weakling and a coward, a man unable of making any kind of decision, let alone a virtuous one.

Finally, the third debate is between Hecuba and Polymestor during the hasty trial—or, rather, mock trial—which concludes the play and it is the only debate from which Hecuba emerges unquestionably victorious. The victory, however, is more than ironic, not only because it justifies two murders and a blinding, but also because, for all of its rational setting and ostensibly logical arguments, it is nothing more than a final ratification of the irreversible irrationality of two once larger-than-life characters now all but reduced to the basest of their animalistic instincts.

Bitter and unpleasant, Hecuba is a play of hopelessness and despair: though it begins as quite the ordinary tragedy featuring a markedly tragic protagonist, by the end of the play, it is quite difficult to point to at least one redeemable quality in any of the play’s characters or to argue that any of the cruel destinies that some of them have already met and other await is unfair or undeserved.

Hecuba Sources

There are many translations of Hecuba available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read E. P. Coleridge’s translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Arthur S. Way blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Euripides, Hecuba, Polydorus, Polyxena

Hecuba Video

Link/Cite Hecuba Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Hecuba". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Hecuba/hecuba.html. Accessed 17 April 2024.