Hippolytus

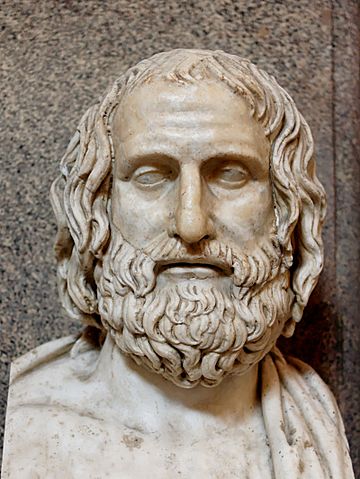

Hippolytus by Euripides

One of two plays of the same title written by Euripides, the surviving Hippolytus was first produced in 428 BC and, unlike the lost one which seems to have been badly received, won the first prize at the City Dionysia of that year. The protagonist of the tragedy is Hippolytus, bastard son of the renowned hero Theseus and a lifetime devotee of Artemis, the goddess of chastity and purity. To punish him for shunning love and sexual pleasures from his earthly affairs, Aphrodite makes Hippolytus’ stepmother Phaedra fall in love with him. This is what Phaedra reveals to her aged nurse at the beginning of the play as the reason why she hasn’t eaten or slept in three days. Convinced that the only cure for Phaedra’s sickness is “the man,” the nurse goes to Hippolytus, and after making him swear not to tell anyone anything, informs him of her mistress’ desires; it is implied that she even goes so far to suggest that Hippolytus should consider yielding to them. Hippolytus, however, is so appalled by the proposition that immediately he launches into one of the most misogynistic tirades in ancient literature, all the while threatening to tell his father everything once he comes back. Distraught by the news, Phaedra takes her own life just before Theseus’ expected return—but not before scribbling a note accusing Hippolytus of attempting to seduce her. After learning of the terrible news from the Chorus, Theseus finds his dead wife’s note and, upon reading it, orders the exile of Hippolytus. He also curses him with death, imploring his father Poseidon to make this wish a reality. Hippolytus maintains his innocence before Theseus, but chooses to remain faithful to the oath given to Phaedra’s nurse and doesn’t reveal Phaedra’s love for him. Soon after Hippolytus leaves into exile, a messenger comes to Theseus with the news that, after being frightened by a bull from the sea, Hippolytus’ horses have torn his chariot apart and, after dragging him among the seaside rocks, have left him all but dead on the shore. Theseus is initially almost content to hear the news, but then Artemis appears on the stage and tells him the truth, blaming him for killing an innocent youth. In the meantime, Hippolytus’ battered body is brought on the stage: with his dying breath, he forgives his father who, in turn, curses cruel Aphrodite and the extent of his own misery. Artemis promises to avenge Hippolytus, by killing Aphrodite’s favorite mortal, Adonis.

Date and Historical Background

According to an ancient hypothesis (or “introduction”), Hippolytus was first acted when Epameinon was Athens’ archon, that is to say, most probably during the fourth year of the 87th Olympiad (428 B.C.). Euripides finished first, Iophon second, and Ion was third. The titles of the other plays of the winning trilogy are not known.

It is important to note that this was not Euripides’ first play on the subject: a few years before it won him the first prize at the City Dionysia, Euripides had treated the myth of Hippolytus and Phaedra in yet another play, also titled Hippolytus. To distinguish between the two, some time in history, a subtitle was added to both tragedies, so, the surviving Hippolytus (especially by scholars) is also known as Hippolytus the Wreath-Bearer, while the lost play is almost always referred to as Hippolytus Veiled.

As far as we can deduce from the available evidence, the lost play was not well received in Ancient Greece, probably because Hippolytus was seduced directly by Phaedra—an act which may have greatly offended the original audience of the tragedy.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Aphrodite, the goddess of love and passion

• Theseus, King of Athens and Troezen

• Phaedra, wife of Theseus and daughter of Minos, the King of Crete

• Hippolytus, son of Theseus and an Amazon

• Phaedra’s nurse

• A messenger, one of Hippolytus’ servants

• Artemis, the goddess of purity and innocence

• Chorus of Trozenian women

• Chorus of Hippolytus’ attendant hunters

Setting

The play is set in the city of Troezen, a coastal town in northeastern Peloponnese, separated from Athens with the Saronic Gulf

Summary of Hippolytus

Prologue

The prologue of Hippolytus, as is customary in Ancient Greek tragedy, provides the audience with the necessary context and background information. It is Aphrodite, the goddess of love and passion, that sets the scene in this case. We learn from her opening speech that, after having murdered Cecrops, Theseus has left Athens with his wife Phaedra and is now serving a year of exile to cleanse himself from the deed in the small coastal town of Troezen. Together with the royal couple is also Hippolytus, Theseus' son by “the Amazon woman.”

Now, according to the goddess, Hippolytus, alone of all citizens of Troezen, thinks of her as “the basest of all divinities.” “He shuns the bed of love and will have nothing to do with marriage,” complains Aphrodite. “Instead, he honors Apollo's sister Artemis, Zeus's daughter, thinking her the greatest of divinities.” Unhappy with Hippolytus’ commitment to lifelong chastity, two years before the events depicted in the play, Aphrodite has inspired Phaedra, Hippolytus’ stepmother, to fall madly in love with him. And it is on this very day that she intends to add the last touches on her infernal plan. “Clearly he does not know that the gates of the Underworld stand open for him and that this day's light is the last he shall ever look upon,” she says before leaving the stage, and soon after noticing Hippolytus and his slave-hunters, coming back from their hunt.

Hippolytus and his followers burst into a hymn praising Artemis (who, as is well known, along with being a chaste goddess, is also the goddess of the hunt). Pointing to a nearby statue of Aphrodite, one of Hippolytus’ attendants warns the prince that it is not a smart idea to overlook her in their prayers, but Hippolytus stubbornly refuses to heed his advice. Everybody leaves afterward: Hippolytus into his royal chamber, and his servants into the kitchen to prepare a meal.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

As soon as Hippolytus and his servants leave, twelve Troezenian women enter the stage, and in the entrance song of the main chorus, express their worries over the health of the queen. “I hear that for three days now,” they sing, “her mouth taking no food, she has kept her body pure of Demeter's grain, wishing because of some secret grief to ground her life's craft in the unhappy journey's-end of death.” The women are unsure about the cause of Phaedra’s illness but worry that she might be possessed by a god—that, they say, or Theseus may have been unfaithful.

First Episode

Preceded by her aged nurse and followed by a few servants, Phaedra comes outside of the palace, as pale and as lifeless as a ghost. Even more worried than the Chorus, Phaedra’s nurse is adamant to find out more about the reasons and keeps asking Phaedra all sorts of questions, eventually pushing her into admitting that she is in love with her stepson, Hippolytus. Both the nurse and the Chorus are horrified to hear this, but Phaedra calms them down: she tells them that she has done nothing so far, nor she plans to, preferring to die rather than spoil her good name. “Only one thing,” Phaedra says, “competes in value with life: the possession of a heart blameless and good.” She intends to keep it—even if that means killing herself. After all, she could never understand women who besmirch their marriage-beds, and there’s nothing she hates more than “women who are chaste in word but in secret possess an ignoble daring.”

Overtaken by her motherly feelings for Phaedra, upon hearing this, the nurse suddenly retracts her initial response to the news of the queen’s love interest, and, after telling her that love is a divine gift (from Aphrodite, of course) that must not be rejected, she suggests another way out. Phaedra doesn’t even want to consider what the nurse’s words imply: “Do not, by the gods, do not, I beg of you, go any further!” “If that is what you wish,” the nurse replies, “I have love-medicine within the house—I just thought of it this very moment—that will free you from this malady without disgrace to you or harm to your mind, if only you do not flinch.”

As the nurse leaves to get this anti-love drug, in the first stasimon (second choral song), the Troezenian women sing a hymn glorifying the power of Eros.

Second Episode

“Silence, women!” abruptly interrupts Phaedra the hymn of the Chorus at the beginning of the second episode. “I am undone!” The reason is terrifying: Phaedra has overheard Hippolytus calling her nurse “pander for the wicked,” and she is sure that her identity is hidden beneath the last word. “She has destroyed me by speaking of my troubles,” cries Phaedra as she heads for the palace. “To die with all speed is the sole remedy for my present troubles,” she adds ominously.

It is at this moment that Hippolytus enters the stage, threatening the nurse to tell the whole world of Phaedra’s wickedness, despite swearing not to beforehand. Horror-struck and disturbed beyond words, Hippolytus asks Zeus why has he created women at all, before bursting into a tirade against the good-for-nothing female sex. Hippolytus goes so far to even say that Zeus should have found another way for men to procreate, because women are either fools who sit at the house and bring only trouble to their husbands or mischievous cheats when they are smart enough to hide their deeds. “May there never be in my house a woman with more intelligence than befits a woman,” Hippolytus shouts, “for Aphrodite engenders more mischief in the clever.”

After venting himself out of his initial anger, Hippolytus promises the nurse to stay loyal to his oath, being a pious and sincere man. This, however, is not enough for Phaedra, who, after happening upon the nurse, condemns her for her betrayal and dismisses her from her duties. Phaedra leaves once again, this time resolved to end her life for good.

In the second stasimon, the Chorus expresses its wish to flee the world and all its troubles, and curses the day when a Cretan ship bore Phaedra to Athens: “It was with evil omen, at the start of her journey and its end, that she sped from the land of Crete to glorious Athens…”

Third Episode

“Ho there! Ho!” a voice is heard from inside the palace. “Help, neighbors of this house! My lady, Theseus' wife, has hanged herself!” Theseus, just arriving home from a secret ambassador mission, overhears the shout and asks the Troezenian women what’s the matter. They tell him, but say nothing of the reason. Phaedra’s body is afterward brought before the devastated Theseus. While mourning her death, he notices a tablet hanging from her hand. He reads the message silently to himself, and after calling upon everyone in earshot to hear, distressingly reveals its content to the whole city: “Hippolytus has dared to put his hand by force to my marriage-bed, dishonoring the holy eye of Zeus.”

Now, some time ago, Theseus had been granted three curses by his father Poseidon, and he sees it fit that he uses one of them now: “kill my son, father Poseidon,” he calls out in his grief, and doesn’t want to take back his prayer despite the pleads of the Chorus that he is making a mistake. Not wanting to leave anything to chance, Theseus also orders the exile of Hippolytus. “Of two fates one shall strike him,” he says, “either Poseidon, honoring my curses, will send him dead to the house of Hades or being banished from here he will wander over foreign soil and drain to the dregs a life of misery.”

Intrigued by the gathered crowd and the loud cries, Hippolytus arrives on the place just in time to hear Theseus’ orders. Even though his father doesn’t want to hear a word out of him, Hippolytus does try to defend himself against Theseus’ accusations. And he presents quite the case. First of all, he says, he is a virgin. Secondly, even if he hadn’t been, Phaedra wasn’t precisely his type, that is to say, he was never physically attracted by her. Thirdly, he was also never one to crave for fame and royal luxuries, always preferring to be a humble hunter and live out of the spotlight. Finally and most importantly, he has sworn to Artemis to always remain pure and chaste and would never break that promise. Even though tempted to add a fifth argument—Phaedra’s own love for him—Hippolytus chooses to remain faithful to the oath given to the nurse and, seeing that Theseus is not interested in changing his mind, sadly accepts his exile.

In the third stasimon, the Chorus laments the fate of mankind in the hands of the gods and, especially, that of Hippolytus: “We have seen Greece's fairest star, have seen him go forth sped by his father's wrath to another land,” they sing. “Oh, I am angry with the gods!”

Exodos (Exit Song)

Not much time passes and a messenger “with a gloomy face” arrives to bring some news that “deserves the concern of all citizens of Troezen.” Hippolytus is “as good as dead,” he announces to Theseus, after a “fierce and heaven-sent” bull had emerged from the sea and frightened the prince’s horses into wrecking his chariot and then dragging his body along the rocks on the shore. Even though he feels “neither pleasure nor pain at these misfortunes,” Theseus orders the messenger to bring him the body of Hippolytus so that he can look him in the eyes once again.

The messenger leaves, and, just then, without warning, Artemis flies down from the heavens. She tells Theseus the truth and blames him for killing a pious man—even if in ignorance. Soon after, a group of servants brings Hippolytus’ body before Theseus, who breaks down in tears and cries for forgiveness. Artemis advises Hippolytus to forgive his father and, in a touching father-son scene, the dying young man acquits his father of his murder, wishing him plenty of joy and happiness. Artemis, in turn, promises Hippolytus two things: that she will avenge his death by killing Aphrodite’s most beloved mortal (though he is not named, she thinks of Adonis), and that she will make sure that his name is never forgotten in the land of Troezen by establishing a cult in his honor.

A Brief Analysis

The story of a youth rejecting the advances of an older—usually closely related—woman is a pretty common theme across ancient cultures, and can be found both in the Egyptian “Tale of Two Brothers,” and in the Bible, where Joseph is falsely accused by Potiphar’s wife of raping her after he refuses to sleep with her. However, Euripides’ treatment of the story is somewhat exceptional, in that, as Artemis implies at the end of the play, one can’t help but feel that it depicts the demise of three innocent people, all of them trying their best to be righteous. And this is often the case in Euripides, which is why Aristotle dubs him “the most tragic” among all poets.

Hippolytus exemplifies yet another common Euripidean trait: especially when compared to the gods of Sophocles and Aeschylus, Euripides’ gods are almost too human, and, when all is said and done, seem to have a lower moral standard than that of the people whom they rule over. For example, even though she advises Hippolytus to forgive his father—and even though it seems that this is what Hippolytus has already done even before Artemis’ suggestion—Artemis herself is unable to forgive Aphrodite, just as the goddess of love had been unable to accept Hippolytus’ preference for another Olympian.

Hippolytus Sources

There are many translations of Hippolytus available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read David Kovacs’ translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Gilbert Murray’s rhyming verse adaptation here.

See Also: Hippolytus, Phaedra, Phaedra and Hippolytus, Euripides

Hippolytus Video

Hippolytus Associations

Link/Cite Hippolytus Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Hippolytus". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Hippolytus/hippolytus.html. Accessed 19 April 2024.