The Bacchae

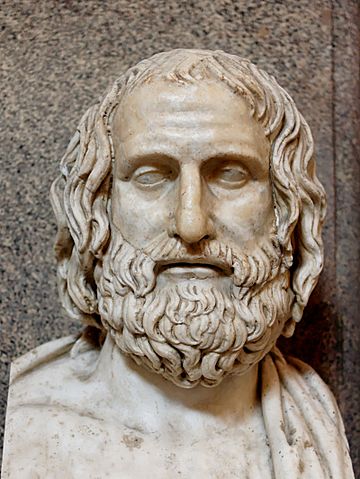

The Bacchae by Euripides

Written by Euripides in the last years of his life and first produced posthumously by his nephew as part of a winning tetralogy at the 405 BC City Dionysia festival, The Bacchae is considered one of the greatest tragedies ever written. It begins with the god Dionysus—son of Zeus and a Theban princess (Semele)—coming to his home city, disguised as a human priest, to avenge the slander that he is not a god. As he explains, many years before the beginning of the play, he was forced out of Thebes by his three aunts (Agave, Ino, and Autonoe) who refused to believe their sister (and Dionysus’ mother) that she had been impregnated by Zeus. Now, he is back to even the score with his mortal family, the daughters and grandsons of Cadmus. And he has already set the wheels of revenge in motion by driving all Theban women, including his aunts, into an ecstatic frenzy, and sending them from the city to the mountains to observe his ritual festivities. The aged Cadmus and the seer Teiresias prepare to join the revels, but Agave’s son Pentheus, the king of Thebes, reproaches them for their simplicity and primitiveness and orders his soldiers to arrest anyone engaging in Dionysian worship. One of the arrested is the disguised Dionysus who is afterward brought before Pentheus and imprisoned in his palace’s stables. However, Dionysus escapes his punishment with relative ease, burning the stables to the ground with lightning and fire. Meanwhile, the attempt to capture the Theban women worshipping Dionysus on the mountain has gone completely awry, and a messenger brings Pentheus the news that the women have now started to run riot over the hillside, stealing bronze and babies, and ripping animals to shreds with their bare hands. Pentheus gathers his army, but before he orders an attack on the Theban women, Dionysus convinces him to change his plans by telling him that it would be much subtler to first spy on the women, dressed just like one of them. Soon after Pentheus and Dionysus leave the royal court, a messenger returns from the mountains and relates the story of how Pentheus was exposed by the Theban women and was subsequently viciously torn apart. Barely he has finished the account, Pentheus’ mother Agave arrives proudly displaying to her father Cadmus what she believes to be the head of a young lion. Cadmus brings her back to reality revealing to her that it is, in fact, the head of her son. Dionysus reveals himself only so that he can justify his vengeance before his devastated mortal family and send his aunts into exile.

Date and Historical Background

The Bacchae was written by Euripides at the court of King Archelaus I of Macedon, where the great playwright spent the last two years of his life. It was first performed a year after his death, at the City Dionysia in 405 BC, as part of a tetralogy that also included Iphigeneia in Aulis and Alcmaeon in Corinth. Directed by Euripides’ nephew—also named Euripides—the tetralogy won the first prize.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Dionysus, son of Zeus and Semele, the god of winemaking and wine

• Cadmus, founder of the city of Thebes, father of Semele and Agave, grandfather of Pentheus and Dionysus

• Pentheus, king of Thebes, grandson of Cadmus, Dionysus’ cousin

• Agave, mother of Pentheus, daughter of Cadmus, Dionysus’ aunt

• Teiresias, a blind prophet

• First messenger

• Second messenger

• Servant

• Chorus of female worshippers of Dionysus (Bacchae or Maenads)

Setting

The play is set before the royal palace of Thebes.

Summary of The Bacchae

Prologue

“Having taken a mortal form instead of a god's,” Dionysus, a lawful son of Zeus and a Theban princess named Semele, has returned to his home town to exact vengeance upon his mortal family. Years ago, he tells us, when he was just a young and helpless boy, he had been banished from the city by his mother’s sisters (Agave, Ino, and Autonoe) who refused to believe Semele that she had been impregnated by the supreme god and, instead, claimed that she had conceived a child from a mortal father and then, encouraged by their father Cadmus, “ascribed the sin of her bed to Zeus.” It was for this boasting, they claimed, that the god killed Semele, when, in fact, she had died after being tricked by Hera to ask Zeus to appear to her as a divinity. Dionysus has now returned from his travels around Asia and, in the guise of a Dionysian priest, has recently driven mad “all the female offspring of Thebes”—including his aunts—and has sent them to observe his ritual proceedings on the nearby Mount Cithaeron, much to the dismay of the mystified Theban men. Pentheus—the ruler of the city and Dionysus’ cousin—is especially against any worshipping of Dionysus. For this, Dionysus threatens, “I will show him and all the Thebans that I was born a god.”

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Dionysus summons up his Lydian female followers—called the Maenads or the Bacchae (Bacchus is another name of Dionysus)—and a Chorus of fifteen women enters the stage, exalting the god of wine in intoxicated ecstasy. Through a wild song, they retell the story of Dionysus’ miraculous birth—Zeus rescued his unborn fetus from the dead Semele and stitched it into his thigh—and call upon Thebes to worship his immense divine power.

First Episode

The famous seer Teiresias arrives at the royal palace and calls for his old friend Cadmus to come and meet him. From the subsequent discussion between the two, we learn that they are old friends and that they have already agreed upon to don fawn-skins, crown their heads with ivy branches and join the Theban women on Mount Cithaeron in celebrating Dionysus. They start dancing their way to the hillside when Pentheus, Cadmus’ grandson, appears before them, barely even noticing the two.

We learn that Pentheus had been away from Thebes when he heard of some “strange evils” wreaking havoc around his city: the women have left their husband’s homes in “contrived Bacchic rites,” and have become part of the hordes of some foreign sorcerer, “a conjuror from the Lydian land, fragrant in hair with golden curls, having in his eyes the wine-dark graces of Aphrodite.” While Pentheus is thinking about what he would do to this man once he manages to catch him, he suddenly sees Cadmus and Teiresias and is ashamed to realize that these two respected Theban citizens have also decided to follow Dionysus. He admonishes them for their baseness and primitiveness, describing the Bacchic rites as an excuse for licentiousness and depravity. Teiresias tries to explain to Pentheus that Dionysus is actually a powerful god and a prophet and that it is not at all wise to mock him, but Pentheus laughs away the advice and threatens to stone to death this foreign “teacher of folly.” As Teiresias and Cadmus leave, the former warns the latter that Pentheus might bring trouble to his house. “I do not speak in prophecy,” the prophet makes it clear, “but judging from the state of things; for a foolish man speaks foolishness.”

In the first stasimon, the Chorus calls upon the minor deity Holiness to remember the sacrilegious words of Pentheus and praises Dionysus for giving an equal pleasure to both the blessed and the less fortunate, while hating everybody who doesn’t lead a happy life by day and a friendly one by night.

Second Episode

A servant enters, leading the chained and disguised Dionysus into the palace courtyard. He explains to the extremely pleased Pentheus that he had no trouble whatsoever arresting the foreigner: in fact, the supposed sorcerer had been so obedient that the servant ended up apologizing to him. In addition, he informs Pentheus, the previously imprisoned Bacchae, have miraculously set themselves free and are now “gamboling in the meadows, invoking Dionysus as their god.” “This man has come to Thebes full of many wonders,” the Servant concludes. “Sensibly take care of the rest.”

Pentheus disregards the Servant’s warning and starts interrogating the disguised Dionysus of the nature of his rites. Calm and composed, the god refuses to answer, telling the arrogant king that it is not lawful for an impious man to hear how his religious ceremonies look like. This enrages Pentheus who threatens to cut off Dionysus’ hair and lock him up for good. Dionysus coolly answers that his god will, nevertheless, find a way to release him before resorting to punish Pentheus for his irreverence. “Shut him up near the horse stable so that he may see only darkness,” screams the insulted and immoderate Pentheus. “Dance there; and as for these women whom you have led here as accomplices to your crimes, we will either sell them or, stopping their hands from this noise and beating of skins, I will keep them as slaves at the loom.”

In the second stasimon, the Chorus reproaches Thebes for rejecting Dionysus and compares the ancestries of its king and the god. “Come, lord, down from Olympus, brandishing your golden thyrsos,” they sing, “and restrain the insolence of the blood-thirsty man.”

Third Episode

“Hear my voice, hear it, Io Bacchae, Io Bacchae!” answers Dionysus the prayers of his followers offstage. “Shake the world's plain, lady Earthquake!” he orders afterward. “Light the fiery lamp of lightning! Burn, burn Pentheus' home!” In panic, the Bacchae fling themselves to the ground and when they raise their heads, Dionysus is beside them, still disguised as the foreign Sorcerer. “But how were you freed…?” they ask, even though they slowly begin to realize that the stranger might be their guardian-god. Still not ready to reveal them the truth, the Sorcerer explains that he had tricked Pentheus into binding a bull instead of him, and that Dionysus set off an earthquake and a fire to aid his escape.

In the meantime, Pentheus rushes out of the palace, alarmed that the Stranger might have used the fire-induced panic to run away from his stable. He is surprised to see him all calm and well in the court yard, but refuses to believe his story that the god Dionysus caused the fire and the earthquake to allow his flight. A Messenger—a cowherd coming from Mount Cithaeron—interrupts the discussion between the two, with a report concerning the strange behavior of the Bacchae. He says that, while climbing up the hill with his cattle, he saw three companies of dancing women, each one led by the three sisters of Semele: Autonoe, Ino, and Pentheus’ own mother, Agave. It was the last one who raised a cry that awoke the others after hearing the footsteps of the horned cattle. What occurred afterward the messenger can only describe as miraculous: the women donned their fawnskins and garlands and started harmoniously dancing around the animals, breastfeeding wolves and piercing rocks with their thyrses, out of which water, wine, milk and honey would leap out.

Understandably, this got the attention of the cowherds who decided to try and capture Agave and bring her back into the palace. The attempt backfired: the frantic Bacchae attacked the men and their herds and ripped the heifers to shreds with their bare hands. The cowherds were lucky to escape and survive. But they were transformed: now they know that these Bacchae must be followers of a real god, because the things they do are beyond the reach of humans. “Receive this god then, whoever he is, into this city, master,” concludes the Messenger. “For he is great in other respects, and they say this too of him, as I hear, that he gives to mortals the vine that puts an end to grief. Without wine there is no longer Aphrodite or any other pleasant thing for men.”

Once again, Pentheus is not interested: instead of looking for supernatural signs in the story of the Bacchae, he focuses on their rowdiness and disobedience and orders their capture and murder. The Stranger manages to change the king’s mind, though, proposing that it might be far better for Pentheus to disguise himself as one of the Bacchae and join him in witnessing firsthand these so-called miracles. Spying is better than shedding blood,

As Pentheus and Dionysus leave, the Chorus bursts into a triumphant song celebrating the success of their guardian-god and expressing their belief that his justice will ultimately prevail.

Fourth Episode

In probably the most self-conscious scene in all Ancient Greek theater, Dionysus, still disguised as the Stranger, leads Pentheus, now disguised as a female bacchant, out of his castle to Mount Cithaeron. Just as a director would in a real play, the god fixes Pentheus’ disguise and gives him advice on how to move and act properly so that he isn’t recognized. The king self-importantly praises his costume and his movements, comparing them to his mother Agave and his aunt Ino. However, it is evident that he has already fallen under the spell of Dionysus and is slowly becoming aware of his divinity: “Oh look!” he exclaims at one point. “I think I see two suns, and twin Thebes, the seven-gated city. And you seem to lead me, being like a bull and horns seem to grow on your head. But were you ever before a beast? For you have certainly now become a bull.” The discussion between Dionysus and Pentheus ends with a dramatic and ambiguous prophecy: after convincing the king that he alone bears the burden of his city, the god promises him that he will return there being carried in the arms of his mother.

The excited and vengeful women of the Chorus take up this image in the fourth stasimon and they sing of Pentheus’ impiety, foreshadowing the king’s death at the hands of his mother.

Fifth Episode

Soon after, a messenger arrives from Mount Cithaeron with some sad and painful news: Pentheus is dead and killed by none other than Agave. Disguised as he was, he tried to climb a tall fir tree to get a better view of the Bacchic rites, and, before disappearing, the Stranger used his supernatural powers to bend down the tree and allow the king to climb to its highest branches. But then, a voice from the heavens declared the presence of an enemy in the tree, and the Bacchae surrounded it and started shaking it until Pentheus fell helpless in the middle of the circle. In a final attempt to save his life, he revealed his identity to his mother, but Agave, intoxicated with Dionysus’ presence, replied to his pleas by pulling her son’s arm out of its socket. The rest of the Bacchae finished the job: they tore Pentheus’ body to pieces and scattered them all over the hillside. To make matters even gorier, Agave took her son’s “miserable head,” fixed it on the end of her thyrsus and, thinking it a lion’s head, is carrying it now in Thebes’ direction, “preening herself on the ill-fated prey, calling Bacchus her fellow hunter, her accomplice in the chase, the glorious victor—in whose service she wins a triumph of tears.”

The Messenger abruptly ends his tale so that he can leave before Agave returns and not witness the calamity. The Chorus fills the ensuing silence with a brief hymn honoring Bacchus and celebrating Pentheus’ death—the fifth and final stasimon.

Exodos (Exit Song)

Soon after, Agave comes back, her son's bloodied head on her thyrsos. “I am bringing home from the mountain a freshly cut tendril to the house, a blessed prey,” she tells joyfully the Chorus. “I caught this young wild lion cub without snares, as you can see.” The Chorus teases her in her madness, endorsing her hopes that the entire city of Thebes will praise her for her deed—including her own son, Pentheus.

Cadmus enters, followed by Servants, each of which carries a different part of Pentheus’ body. Agave proudly displays the last one to her father, still maddened and still believing that it is a lion’s head that she has brought back home. Because of this, Agave is immensely confused at her father’s “morose and sullen” response, and calls out for her son Pentheus to come out of the palace and marvel at her achievement. Though still distressed, Cadmus helps Agave come to her senses, but only so that she can realize that it is her son’s head that she has returned with from Mount Cithaeron.

As the two grieve Pentheus’ death and discuss his impiety—while remembering fondly his once gentle nature—Dionysus appears on the roof of the palace, finally in his divine form. He sends Agave and her sisters into exile, and decrees the ambiguous future of Cadmus and his wife Harmonia. “You will become a dragon,” he says to the founder of Thebes, “and your wife, Ares’ daughter, will take the form of a serpent. And as the oracle of Zeus says, you will drive along with your wife a chariot of heifers, ruling over barbarians. You will sack many cities with a force of countless numbers. And when they plunder the oracle of Apollo, they will have a miserable return, but Ares will protect you and Harmonia and will settle your life in the land of the blessed.”

In the last verses of the play, almost customarily for Euripides, the Chorus sings of the miraculous power of the gods and commends their ability to make the impossible—possible.

A Brief Analysis

According to numerous interpreters, Euripides’ last play might be the greatest of Greek tragedies; it is certainly—with Aeschylus’ Oresteia, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and Antigone, and Euripides’ very own Medea—the most discussed and adapted one in modern times. It is not only exceptional in structural manner—both the Chorus and the god are integrated in the plot, with the latter’s appearance as deus ex machina perhaps more motivated than that of any other god in surviving Greek tragedies—but also in terms of imagery and dramatic power. It is striking how modern some aspects of the play seem even two and a half millennia after its original production: Pentheus’ gruesome death (almost certainly an invention of Euripides), the metatextual discussion between Dionysus and Pentheus preceding it, the double vision of the king and its nuancedly developed links to the twin-nature of the god, and, particularly, the way Pentheus’ demise into madness is portrayed—in Jungian terms, it can easily be analyzed as the direct consequence of the king repressing his Dionysian side for too long and becoming a victim of his overexpressed rationality (much like the main protagonist in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice). It is difficult to say today what Euripides’ original intention with this play were. Did he try to deliver one last blow to religion by depicting it as “hostile force to civilization,” or did he do the very opposite, repenting his lifelong cynicism and admitting that lack of religious devotion might eventually lead to the end of humanity? The fact that, at different periods, both answers have been considered valid, should be considered a definite testament to Euripides’ timeless creative genius.

The Bacchae Sources

There are many translations of The Bacchae available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read T. A. Buckley’s translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Arthur S. Way blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Dionysus, The Wanderings of Dionysus, Pentheus, Euripides

The Bacchae Video

The Bacchae Associations

Link/Cite The Bacchae Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "The Bacchae". GreekMythology.com Website, 30 Jan. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/The_Bacchae/the_bacchae.html. Accessed 19 April 2024.