The Phoenician Women

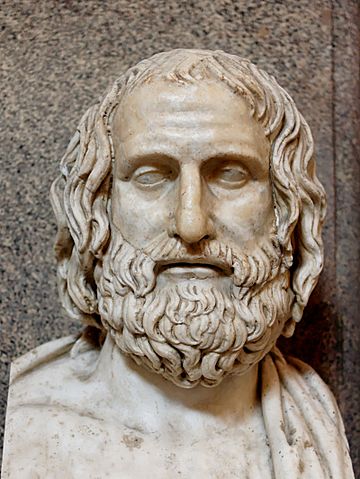

The Phoenician Women by Euripides

First performed sometime between 411 and 409 BC, Euripides’ late play The Phoenician Women is based on the same story as Aeschylus’ early tragedy, Seven Against Thebes. The play begins with a monologue by Jocasta, the queen of Thebes, in which she sums up the story of her son and husband, Oedipus, and the couple’s two sons, Eteocles and Polyneices. She informs us that a year or so before the events told in the play, the brothers imprisoned Oedipus within his palace so that his deeds might be forgotten, but Oedipus cursed them to divide the city with blood and sword. To avert the curse, the brothers agreed to split the time between them, but, contrary to the agreement Eteocles has failed to yield power to his brother after a year’s rule. Now, Polyneices wants revenge and, after gathering a huge army from Argos, he has just arrived to besiege his own city. Hoping that war might still be avoided, Jocasta tries to reconcile her two sons; unfortunately, she is unsuccessful. Soon after, Eteocles meets his faithful advisor Creon, Jocasta’s brother, and, using some information taken from an Argive prisoner, the two plot the defense of Thebes. After Eteocles leaves, following his orders Creon meets with the blind Theban seer, Teiresias, while in the company of his own son Menoeceus. Teiresias reveals to Creon that no plan would ever save Thebes unless Menoeceus is sacrificed to Ares, the god of the war. Deeming this too great a price to pay, Creon immediately starts making another plan—that of sending his son away from Thebes. Menoeceus, however, has plans of his own and, as soon as he is left alone, commits suicide in an attempt to save his city. A messenger arrives and brings news of the demise of the enemy leaders at six of the Seven Gates of Thebes and informs Jocasta that the winner of the war will be decided in a single combat between the two brothers at the seventh gate. Jocasta takes Antigone and the two rush to prevent the worst, but later on, a second messenger reveals that not only the brothers had killed each other, but also that Jocasta has killed herself over their bodies. Already aged and blind, Oedipus suddenly exits the palace only to be sent into a new exile by the new ruler of Thebes, Creon, who also proclaims that Polyneices’ body must be left unburied.

Date and Historical Background

Although no fixed date is given by ancient sources, The Phoenician Women was almost certainly first performed at the City Dionysia between 411 BC and 409 BC. Euripides left for Macedonia soon after the production of Orestes in 408 BC, so we can be certain that the play must have been produced before that, and at least a year after 412 BC, since an ancient scholiast wonders, on the margins of the 53rd verse in Aristophanes’ Frogs, why the great comedian chose to mention Andromeda in his play and not a “more recent” tragedy by Euripides, such as Hypsipyle, Antiope, or Phoenician Women; we know for a fact that the now-lost Andromeda was part of a trilogy that included Helen and was first performed in 412 BC. As a matter of fact, metrical evidence suggests that The Phoenician Women must be close in date to Helen and, based on its content alone, it should also be close to the oligarchic revolution in Athens in 411 BC—which seems like the most probable date for its first production.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Oedipus, former king of Thebes

• Jocasta, mother and wife of Oedipus

• Antigone, daughter of Oedipus and Jocasta

• Tutor, an attendant of Antigone

• Eteocles, king of Thebes, son of Oedipus and Jocasta

• Polyneices, brother of Eteocles, son of Oedipus and Jocasta, now exiled

• Creon, brother of Jocasta, advisor to Eteocles

• Menoeceus, son of Creon

• Teiresias, a blind Theban prophet

• Chorus of Phoenician women on their way to Delphi

• First Messenger

• Second Messenger

Setting

Thebes, at the time of the invasion by the Seven.

Summary of The Phoenician Women

Prologue

In the first part of the prologue, Jocasta, the queen of Thebes, summarizes the story of her son/husband Oedipus and its aftermath. After going over the better-known parts of the legend—Oedipus killing his father Laius, then guessing the Sphinx’ riddle, then marrying his mother in ignorance and fathering with her four children: Eteocles, Polyneices, Antigone, and Ismene—Jocasta reveals that, once the story was made known, Eteocles and Polyneices “hid their father behind bars, so that his misfortune… might be forgotten.” In other words, Oedipus is still alive and is imprisoned the building that was once his palace. Affected by his fate, from the inside of his cell, he repeatedly “makes the most unholy curses against his sons, praying that they may divide the house with a sharp sword.” Afraid that the gods might answer his prayers, a year before the beginning of the play, Eteocles and Polyneices made an agreement to change places on the throne every year. However, once the first year passed, Eteocles refused to abdicate his power, so Polyneices went to Argos, married into the family of Adrastus, and gathered a large Argive army in an attempt to take back what he deems was rightfully his. To end their strife, Jocasta has just persuaded one son to meet the other under truce, and prays to Zeus that the discussion leads to reconcilement before entering the palace.

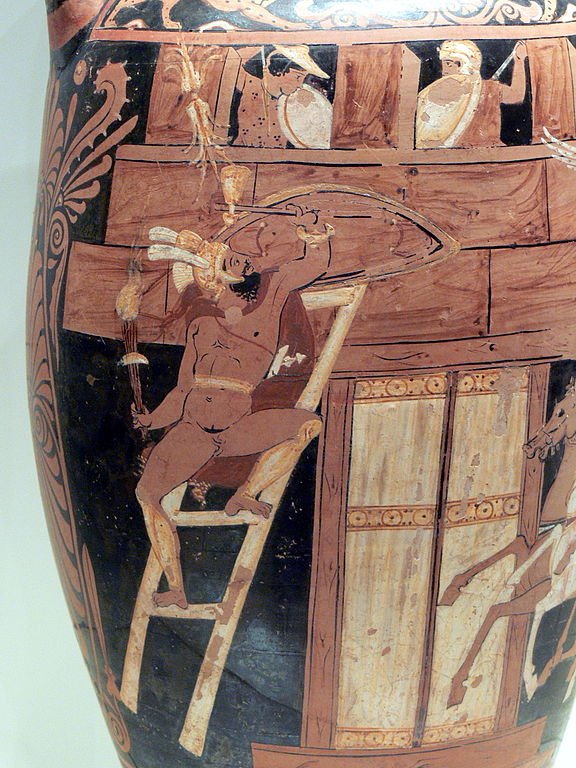

Just then, Antigone and her Tutor appear on the roof of the palace. Antigone starts asking the old man questions about the identity of the invaders and the Tutor answers them all. During the discussion of the two, we learn the names of the Seven leaders of the Argive army attempting to conquer Thebes: Tydeus, Capaneus, Adrastus, Hippomedon, Parthenopeus, Amphiaraus, and Polynices himself. Upon noticing a crowd of women coming toward the royal palace, the Tutor orders Antigone to go inside and stay beneath the shelter of her maiden chamber, since confusion is about to rattle the city.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

We now turn our attention to the crowd of women noticed by Antigone’s Tutor. They identify themselves as foreign visitors on their journey from Phoenicia to Delphi and as specially chosen servants of Apollo. However, they also reveal that they share some remote ancestral ties with Thebes. “A friend's pain is shared,” they sing, “and if this land with its seven towers suffers any mischance, Phoenicia's realm will share it.”

First Episode

Polyneices overhears the Phoenician women and asks them some more about their mission. As soon as he reveals his identity before them, his mother, Jocasta, exits the palace and, upon seeing Polyneices, bursts into an emotional monologue teeming with rhetorical questions and painful regrets. “What can I say to you?” she asks sorrowfully. “How in every way, by hands, by words, in the mazy delight of the dance, shall I find the pleasure of my former joy?” After bemoaning the fact that she never got the chance to see her son get married, Jocasta curses her two husbands and even the gods for allowing things to come to this. “Whether the sword or strife or your father that is to blame,” she says, “or heaven's visitation that has burst riotously upon the house of Oedipus—on me has come all the anguish of these evils!” A dialogue ensues between Jocasta and Polyneices, during which the son reveals to his mother the things he had to go through in exile. He also tells her of the oracle that brought him to Argos, his happy marriage, and Adrastus’ oath that helped him persuade the Argive army to come with him to Thebes. “I call the gods to witness,” Polyneices concludes, “that it is not willingly I have raised the spear against my willing friends. But it belongs to you, mother, to dissolve this unhappy feud, and, by reconciling loving brothers, to end the trouble for me and you and the whole city.”

Just then, Eteocles arrives and a formal debate follows between the two brothers with Jocasta acting as the arbitrator. After reexplaining his situation, Polyneices insists that justice is on his side, since, per the agreement between the brothers, he willingly left Thebes and allowed Eteocles to rule the country for one full year, on condition that he should then take up the rule in turn. If he is granted that, Polyneices promises to not only dismiss the Argive army, but to give back the throne to his brother once the year passes. Firmly believing that “fairness and equality have no existence in this world beyond the name,” and that “it is cowardly to lose the greater and to win the less,” Eteocles rejects Polyneices’ proposal and offers him to come back to Thebes on any other terms but that of ascending to the throne. Upon hearing them out, Jocasta reprimands both her sons—Eteocles for his ambition, Polyneices for allying with foreigners—and makes a strong case for justice and equality. Both brothers are faced with a simple either/or situation, she says, and the alternative to ruling Thebes is saving it. Why would they choose the former? They, nevertheless, do: adamant that they can never be reconciled except upon their own terms, Polyneices and Eteocles split after a harsh exchange which leaves no room for hope that the war may be averted.

Now that an attack on Thebes becomes more than inevitable, in the first stasimon, the Phoenician women recount the story of Cadmus and the Spartoi, an event that led to the city’s miraculous foundation. They ask the gods for help and express hope that Thebes will be spared from destruction.

Second Episode

Summoned by Eteocles, Creon arrives before his palace and reveals to him that an Argive prisoner has told them that the attackers, led by their seven best men, plan to storm all seven gates at once and, thus, make full use of their numbers. “What are we to do then?” asks Eteocles. “I will not wait till every chance is gone.” “You also choose seven men to set against them at the gates,” answers Creon. Eteocles agrees with him and as he leaves to choose the seven bravest Theban soldiers, he instructs Creon to “ask Teiresias, the seer, if he has anything to say of heaven's will.” In addition, he also commands him—if he should die during the attack—to make sure that nobody would “give Polyneices' corpse a grave in Theban soil, and let the one who buries him die, even if it is a friend.”

In the second stasimon, the Chorus once again invokes the gods and remembers some better days of Thebes. “In days gone by the sons of heaven came to the wedding of Harmonia,” they sing, “and the walls and towers of Thebes rose to the sound of Amphion's lyre…”

Third Episode

Led by his daughter and Creon’s son Menoeceus, the blind seer Teiresias enters and demands to know the reason why he has been fetched to the palace. Creon tells him that he has been ordered by Eteocles to inquire of him “the best course to save the city.” Teiresias replies that it is only because of Creon he will answer the question; if Eteocles had asked him the same, he would have never answered because the best course was always “to prevent any child of Oedipus becoming either citizen or king in this land, since they are possessed and would overthrow the city.” There is another way, he adds, but refrains from sharing it with Creon, telling him bluntly that as much as he wants to save his country now, he would want the opposite once he learns how he can do that. Creon insists to know and declines to shelter his son from the prophet’s divinations. “Then hear the intent of my oracle,” replies Teiresias. “You must sacrifice Menoeceus, your son here, for your country, since you yourself are calling on fate.” True to Teiresias’ expectations, Creon immediately renounces his city and begs Teiresias to tell nobody his news. And the second the prophet leaves, he turns to Menoeceus and implores him to “fly with all haste away from this land, regardless of these prophets' reckless warnings.” Menoeceus agrees, but once his father has left, he vows to sacrifice himself for Thebes, for everything else would be shameful. “If each were to take and expend all the good within his power,” Menoeceus concludes before leaving, “our states would experience fewer troubles and would prosper for the future.”

In the third Stasimon, the Phoenician women continue their story of Thebes, this time singing of the Sphinx and Oedipus, as the one-time savior of the city.

Fourth Episode

A messenger arrives before the palace and after summoning Jocasta, he describes to her the mighty enemy and the course of the battle before the gates. The Thebans are winning, he reveals, but unfortunately, Jocasta’s two sons have decided to fight one-on-one for the throne. “If you have any power or subtle speech or charmed spell,” the Messenger brings his speech to a close, “go, restrain your children from this terrible combat, for great is the risk they run. The prize of the contest will be grievous sorrow for you, Jocasta, if today you are deprived of both your sons.” Jocasta immediately calls for Antigone to come out of the house, and the two leave urgently to the seventh gate to prevent the two brothers “from plunging into death and falling by each other's hand.”

In the fourth stasimon, the Chorus laments the seemingly inevitable fratricide in advance. They cut short their lamentations once they see Creon coming their way “with clouded brow.”

Exodos (Exit Song)

“Ah me!” shrieks Creon upon entering, “What shall I do? Am I to mourn with tears myself or my city? My son has died for his country, bringing glory to his name, but grievous woe to me!” Creon interrupts his wailing to ask the Chorus for Jocasta’s whereabouts: he needs her to bathe his child’s corpse and lay it out. The women tell him that Jocasta and Antigone have gone to the battlefield to stop Eteocles and Polyneices from killing each other. Creon can barely express his surprise at the news when a second Messenger arrives before the palace and brings some terrible news: not only Eteocles and Polyneices have murdered each other, but Jocasta, overcome with grief, has committed suicide over the corpses of her sons as well!

The Chorus bursts into a lament, and during it, Antigone enters, followed by servants bearing the bodies of Jocasta and her two sons. Antigone’s dirge over the three corpses is interrupted by the sudden appearance of Oedipus, who cannot believe that his curses have claimed the life of his mother/wife as well. Creon orders everybody to cease their lamentations and makes three important proclamations. First, that Eteocles has left him to rule the land by giving the kingdom as dowry to his young son, Haemon, as part of his future marriage to Antigone. Second, that in accordance with Teiresias’ prophecies, Oedipus must be exiled from Thebes so that the city has any chance to prosper.And finally, that Polyneices must not be buried and that “whoever is caught decking his corpse with wreaths or giving it burial, shall be requited with death.” Antigone defies Creon’s orders. The play ends with Antigone and her aged father sharing their misfortunes in a lyric duet, and with Oedipus departing to his exile. “Greatly revered Victory,” sings the Chorus, “may you occupy my life and never cease to crown me!”

A Brief Analysis

A typically bold Euripidean retelling of an already celebrated story, The Phoenician Women differs significantly from other treatments of the subject: in Euripides’ play, both Jocasta and Oedipus are alive at the time of the Seven, and there are no earlier sources for the subplot of Creon and Menoeceus. These additions routinely confirm Aristotle’s description of Euripides as “the most tragic of all poets”: as if fratricide isn’t a subject tragic enough for a dramatic treatment in itself, Euripides adds not only another immensely tragic element to the plot (a living mother committing suicide over her sons’ dead bodies), but also a fairly unrelated subplot dealing with self-sacrifice as well.

There’s, of course, a reason for this: Menoeceus and Jocasta serve as antidotes to Eteocles and Polyneices, both putting their own agendas before the needs of their community. The two represent the lowest kind of love, one that can barely be considered as such: self-love. Jocasta and Creon represent a higher form of love: filial love. Though she knows that Eteocles is wrong to have kept the crown past his allotted year, and Polyneices is wrong to have attacked his own city with a foreign army, Jocasta loves both of them equally because they share her blood. For the very same reason, Creon—unlike, say, Agamemnon in the case of Iphigenia—prefers to smuggle his son away from Troy rather than sacrifice him to save his community.

However, Menoeceus—who represents the highest form of love: altruistic love—decides to put the needs of his larger community before his very own life: through his self-sacrifice, he not only saves Thebes, but also, to a certain extent, counterbalances the effects of Eteocles and Polyneices’ self-love.

The Phoenician Women Sources

There are many translations of The Phoenician Women available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read E. P. Coleridge’s translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Arthur S. Way blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Oedipus at Colonus, Oedipus Rex, Seven Against Thebes, Euripides

The Phoenician Women Video

The Phoenician Women Associations

Link/Cite The Phoenician Women Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "The Phoenician Women ". GreekMythology.com Website, 30 Jan. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/The_Phoenician_Women_/the_phoenician_women_.html. Accessed 25 April 2024.