Trojan Women

Trojan Women by Euripides

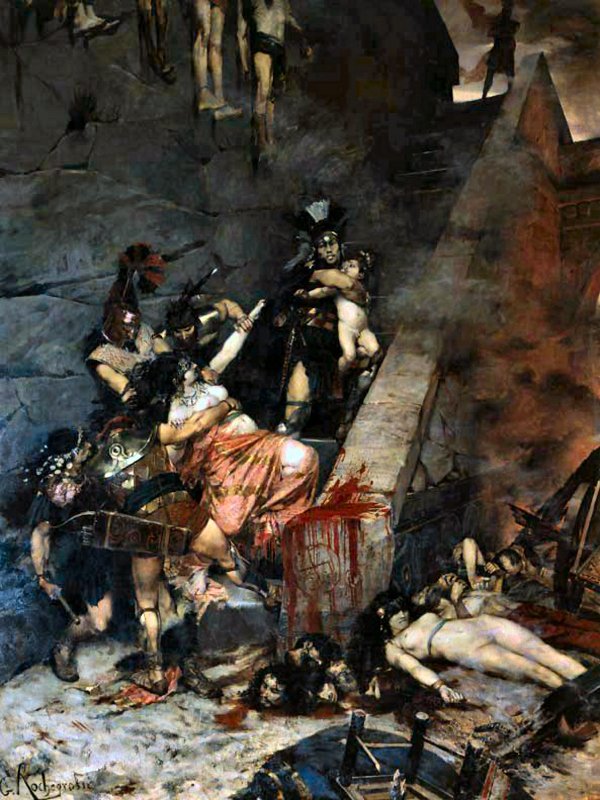

Produced in 415 BC for the City Dionysia, Euripides’ Trojan Woman was the third tragedy of a second-prize winning trilogy dealing with the Trojan War. It follows the fates of four renowned Trojan women – Hecuba, Cassandra, Andromache, and Helen – after the immediate sack of Troy. The play, however, opens with a “divine prologue” featuring a discussion between the sea-god Poseidon, who favored the Trojans, and Athena, the dedicated supporter of the Greeks. As the former is saying farewell to his ruined city, the latter, insulted by the blasphemous behavior of some of the Greek invaders (who have desecrated one of her temples), asks Poseidon’s help in destroying their fleet as the Greeks return home. Poseidon happily obliges. As soon as the gods disappear, Queen Hecuba and a Chorus of Trojan women emerge, lamenting the fact they are bound to become slaves to their invaders, and wondering what precise fate might befall them. Talthybius, the Greek herald, reveals this to them, announcing that Cassandra is to be allotted to Agamemnon, Andromache to Neoptolemus, and Hecuba to Odysseus. Before too long, Cassandra is forcibly taken to her new master: in a prophetic frenzy, she predicts Agamemnon’s murder and Odysseus’ future troubles before being carried away by Talthybius. Hector’s widow Andromache appears, followed by her young son Astyanax. She is desolate and suicidal, but her mother-in-law Hecuba persuades her to endure, if only for her son, who may one day grow up to become a hero like his father and rebuild Troy. Hecuba’s hopes are short-lived: Talthybius comes back to proclaim that Astyanax must die for fear of future revenge. Andromache attempts to fight the verdict, but she is powerless: her son is carried off to his death and she can do nothing but say a tearful goodbye to him. In the midst of the horror, Menelaus arrives among the Trojan women, angry at his wife Helen for starting the Trojan War and resolved to kill her. Helen wants to say something in her defense, and, at the insistence of Hecuba, she is eventually allowed. The two women debate Helen’s guilt, and Menelaus eventually declares in favor of Hecuba; even so, against Hecuba’s advice, he postpones his revenge until the two reach Greece. Talthybius comes back and brings in the body of Astyanax, laid down on the shield of Hector. A touching lament by Hecuba and a humble and speedy burial follow. As the walls of Troy collapse down in flames, the Trojan women are taken to the Greek ships. The stage is left empty.

Date and Historical Background

Trojan Women was presented at the City Dionysia in the spring of 415 BC and won the second prize. It was the third play of a tragic trilogy, following two other unconnected but Troy-themed plays: Alexander (which treated the recognition of Paris by his parents) and Palamedes (which dealt with Greek mistreatment of the title character). Customarily, the tragic trilogies were followed by a satyr play, in the case of this one, one titled Sisyphus.

Though nowadays Trojan Women is considered a masterpiece, Euripides didn’t win that year’s competition, finishing second to Xenocles, a tragedian often ridiculed by Aristophanes, who got his first victory with Oedipus, Lycaon, Bacchae, and Athamas, a satyr-play. Commenting upon the decision of that year’s judges, Aelian, a Roman writer of the second century AD, wrote the following in his Various Histories: “It is ridiculous that Xenocles should not be worsted, and Euripides get the better, especially in these tragedies. One of these two must have been the reason: either that they who gave the votes were ignorant and void of clear judgment, or corrupt. But both are dishonorable, and unworthy the Athenians”

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes (patron god of Athens)

• Athena, goddess of wisdom, handicrafts, and war (patron goddess of Athens)

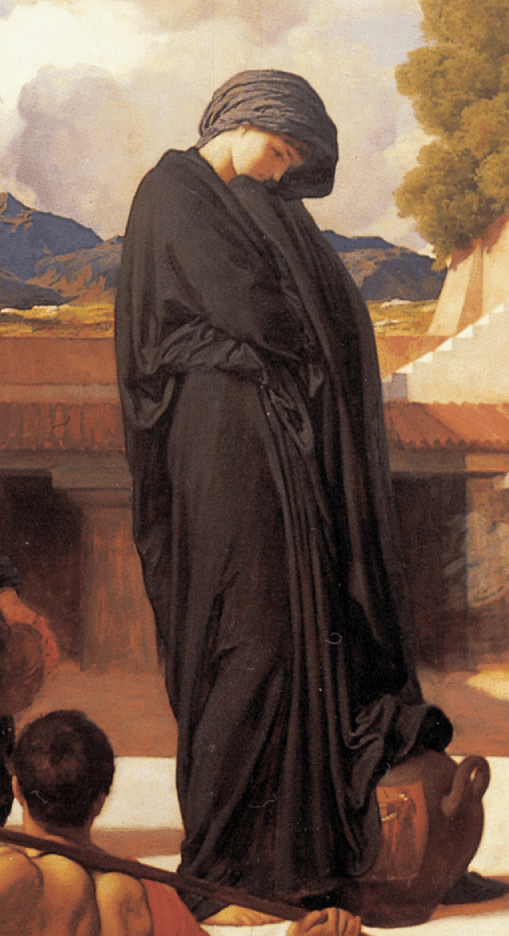

• Hecuba, queen of Troy, wife of Priam, and mother of Hector, Paris and Cassandra

• Cassandra, daughter of Hecuba and Priam, priestess of Apollo

• Andromache, wife of Hector, daughter-in-law of Hecuba and Priam

• Helen, wife of Menelaus before fleeing with Paris (Alexander), daughter-in-law of Hecuba

• Talthybius, herald of the Greek army

• Menelaus, one of the leaders of the Greek army, Helen’s first husband

• Chorus of Trojan women

Setting

The scene is the ruins of Troy, soon after the fall of the city to the Greeks.

Summary of Trojan Women

Prologue

Trojan Women opens with a monologue spoken by Poseidon. He describes the sack of Troy and attributes the desolation of the city to two goddesses: Hera and Athena. Bidding farewell to the once happy city he had built himself with the help of Apollo, Poseidon lists many of its famous and unhappy inhabitants, pointing in the direction of its former queen Hecuba, now lying asleep among the ruins. “Farewell, o city once-prosperous!” Poseidon exclaims. “Farewell, you ramparts of polished stone! if Pallas, daughter of Zeus, had not decreed your ruin, you would be standing firmly still.”

As if summoned by the very mention of her name, Athena appears out of nowhere and asks to make peace with Poseidon. Her reason: Ajax the Lesser, a Greek soldier, has dragged away the Trojan princess Cassandra by force from the altar of one of Athena’s temples, and “the Achaeans did nothing, said nothing to him.” Due to this sacrilege, Athena is adamant to punish the Greeks and wants Poseidon’s help. “Help me make their return one of no return,” says Athena. “Make the Aegean strait to roar with mighty billows and whirlpools, and fill Euboea's hollow bay with corpses, that Achaeans may learn henceforth to reverence my temples and regard all other deities.” Poseidon is more than happy to oblige.

As the two gods disappear, Hecuba wakes from her sleep and bursts into a monody for the fate of Troy and her own misfortunes. “Ah me! ah me!” she cries. “What else but tears is now my hapless lot, whose country, children, husband, all are lost?”

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Several Trojan women overhear Hecuba’s cries and join her in a kommos (a lyrical song of lamentation). Then they ask their queen for some news. Hecuba answers them that the Greeks are due to sail back to their homeland that very day and that she and all other Trojan women are about to find out whom they have been assigned to as slaves. “I look my last on my children's bodies, my last” the leader of the Chorus sings, “I shall endure surpassing misery, either as the unwilling bride of some Hellene or as a wretched slave from Peirene's sacred fount I shall draw their store of water.”

First Episode

Talthybius, the herald of the Greek army, arrives before the walls of Troy and announces that “the lot has decided the fate” of the Trojan women. “To whom has the lot assigned us severally?” asks Hecuba, and, one by one, Talthybius reveals the allocations: Agamemnon has chosen the virgin Cassandra for himself even before the lot; Polyxena, another daughter of Priam and Hecuba, has been appointed to minister at Achilles’ tomb; Andromache, Hector’s wife, is to go with Achilles’ son, Neoptolemus; and, finally, Hecuba is to become the servant of Odysseus – a man she deems not only a “hateful treacherous foe” and “a monster of lawlessness,” but also the worst of all Greeks. “Ah, woe! a victim to a most unhappy lot!” cries she after hearing out Talthybius.

The Greek herald, for his part, calls on his soldiers to fetch Cassandra to be taken away to Agamemnon. That proves to be unnecessary since Cassandra arrives herself just a moment later. Possessed by Apollo, she is deep within one of her trances, hallucinating a wedding procession and dancing to an imaginary tune, carrying lighted torches and singing a mock wedding song for herself and Agamemnon. “O mother, crown my head with victor's wreaths and rejoice in my royal match,” she says suddenly and curiously to Hecuba who, grief-stricken, asks that the Trojan women drown Cassandra’s wedding song with tears. “If Apollo is indeed a prophet,” Cassandra goes on, “Agamemnon, that famous king of the Achaeans, will find in me a bride more vexatious than Helen. For I will slay him and lay waste his home to avenge my father's and my brothers' death.”

In addition to foretelling the fall of the House of Atreus – and afterward, at length, even Odysseus’ future troubles – Cassandra also spends some time explaining why the Greeks did not actually win the Trojan war and attempts to prove her fellow citizens “happier far than those Achaeans.” Her main argument is that the best of the Greek men have spent the last ten years of their lives in another land, dying far from their beloved wives, who have themselves turned into dying widows in the meantime. As opposed to them, the Trojans fought for their fatherland (“the fairest fame to win”) and could always return to their families and friends at the end of the day – or, in case they didn’t survive the battle, rest assured that they’d be “laid to rest in the embrace of their native land, their funeral rites all duly paid by duteous hands.”

Having had enough with her rants, Talthybius takes Cassandra off. Hecuba collapses to the ground, and, rejecting the offer for help from the Trojan women, tells her personal tale of woe: a once-mighty queen and mother of numerous children, now an old slave with no hope that anyone – let alone her sons or daughters – could help her. In the first stasimon, the Trojan women pick up Hecuba’s tale and sing of the night of Troy’s fall.

Second Episode

Disturbed by a sight in the distance, the Trojan women cut short their song. “Hecuba,” they ask their queen, “do you see Andromache advancing here on a foreign chariot? and with her, clasped to her throbbing breast, is her dear Astyanax, Hector's child.” Made aware of their presence, Hecuba immediately starts sobbing – both for Andromache’s and her own fate. In the discussion that follows between the two, Andromache reveals to Hecuba that, as previously foreboded, the Greeks have killed Polyxena at Achilles’ grave. She adds afterward that – as terrifying as this is – she would prefer Polyxena’s fate to her own: becoming a slave woman at the home of her husband’s murderer; she even implies that she is hopeless to the point of wishing death. Hecuba attempts to console her and tells her daughter-in-law that, if not for something else, she has a duty to go on living for the sake of her child, the only hope that in some future Troy might be rebuilt again.

Ironically, it is at this very moment that Talthybius returns with the news that Odysseus has persuaded the Greek leaders that Astyanax must be killed, “thrown from Troy's battlements.” “Oh me!” cries Andromache, “this is worse tidings than my forced marriage…” She tries to resist, but, eventually, she realizes that she can do nothing more but say a tearful and moving goodbye to her beloved boy. As the Greek soldiers lead Astyanax away, Andromache curses the cruel and cunning enemies of Troy, reserving her worst insults for Helen, simultaneously renouncing her divine heritage and describing her as a daughter “born of many a father, first of some evil demon, next of Envy, then of Murder and of Death.”

In the second stasimon, the Trojan women sing of Troy’s past happiness, affluence and prosperity. “But all the love the gods once had for Troy is passed away,” they mournfully conclude.

Third Episode

Followed by attendants, Menelaus enters, joyful that finally the day has come when he can punish his wife Helen for eloping with Paris and causing so much misfortune to so many people. However, he immediately adds that he has resolved to delay the final part of the punishment until after the two return to Argos. Deeming him always just, Hecuba thanks him for the decision but scolds him for the delay. Brought in by Greek soldiers at that very moment, Helen asks Menelaus and Hecuba to speak in her own defense: “May I answer this decision, proving that my death, if I am to die, will be unjust?” Menelaus turns her down, but Hecuba urges him to give Helen a chance to make her case and be heard.

Helen claims that she is innocent and points the finger of blame in the direction of Hecuba and Aphrodite: it was the former who gave birth to Paris, and the latter who charmed her to fall in love with the Trojan prince, coming with him to Sparta. Moreover, Helen smartly adds, it was her own beauty that saved Greece from utter destruction because if she hadn’t been as beautiful as she is, Paris would have given the golden apple to either Hera or Athena – and they both promised him eternal military glory and even victory over Greece.

Hecuba begs to differ, and accuses Helen of lying about everything: neither Athena and Hera could have promised Greece to a Trojan (in the former case, the goddess herself would have become a slave to foreigners herself, being the protector of the city of Athens) nor could Aphrodite ever followed Paris to the house of Menelaus to mesmerize her into elopement (being a goddess, she could have brought Hellen to Troy while sitting quietly in the heavens). Everything – from the elopement to the Trojan War to this last speech – is the unfortunate product of the wicked mind of Helen, a greedy, conniving, self-righteous two-time princess unworthy of her titles or beauty.

Menelaus agrees with Hecuba and orders that Helen be immediately stoned. “Oh, by your knees, I implore you, do not impute that heaven-sent affliction to me, or slay me; forgive me” – shouts his former wife. Menelaus, against Hecuba’s advice, once again reverts to his previously planned delay: Helen is to be killed, but in Argos.

Dragging Helen with him, Menelaus leaves, leaving the Trojan women to bewail, yet again, the fate of Troy, now utterly abandoned by its gods.

Exodos (Exit Song)

Barely is the Chorus’ song done, when Talthybius comes back with his men and the body of Astyanax laid down on Hector’s shield. Thanks to the pleas of Andromache—now sailing with Neoptolemus to Greece—the Greek leaders have allowed a burial for her son, and it is Hecuba’s duty to perform the rites. In order to speed up the deed, Talthybius has already bathed Astyanax’s corpse and cleansed its wounds, and he and his men promise to dig up a grave; Hecuba only needs to deck the body with wreaths and flowers.

Before doing that, Hecuba asks that Hector’s shield be placed to the ground so that she can see the lifeless body of Astyanax herself. While the women bring robes to clothe him and flowers to adorn his hair, Hecuba addresses her dead grandson in a touching lament, which ends with a shared kommos with the Chorus after Talthybius and his men carry the corpse out for burial.

That is, unfortunately, not the end of the misfortunes of Troy’s women: Talthybius returns shortly after to order the remaining Greek captains to “fire this town of Priam.” Standing before the flames, Hecuba ponders throwing herself into them but is prevented by the soldiers. As she and the Trojan women are led away by the Greeks, they lament their once-glorious homeland: “The name of my country will pass into obscurity; all is scattered far and wide, and hapless Troy has ceased to be.” The stage is left empty.

A Brief Analysis

In the summer of 416 BC, in the middle of the Peloponnesian War, Athens invaded the small island of Melos with about three thousand and five hundred men. Though it had made some small donations to Sparta, Melos managed to remain largely neutral during the war. Now, the Athenians wanted to change that: they offered Melians the choice of either becoming an Athenian ally for the rest of the war or risking total annihilation. Melos opted for the latter. By the end of the year, the Athenian soldiers not only captured the city but also executed all men and sold all Melian women and children into slavery.

Since it was produced the very next year, the Troy-themed tragic trilogy that included Trojan Women is often thought of as an artistic commentary by Euripides on the Melian siege. Even though it would be difficult to say that it is an “anti-war tragedy,” Trojan Women is obviously, at the least, “questioning the usefulness of war, and this at a time when Athens has been fighting Sparta for 15–16 years” (Ann Suter). As such, it is certainly a political play, but not of the patriotic sort as Euripides’ earlier Suppliants and Children of Heracles are. On the contrary, in fact: some even suggest that its main message might have been directed as a protest towards the politicians in Athens, who were at the time discussing the possibility of yet another expedition to Sicily, urging abandonment of the idea.

Told from the point of view of defeated foreign women, Trojan Women is not only moving and poignant but also utterly hopeless and pessimistic. Its curious structure contributes to the latter: the play, as many critics have noted, lacks not only unity and direction but also peripeties and denouement. In fact, it is perhaps the only surviving Greek play where the events announced in the prologue never actually happen within the play. As one scholar (Francis M. Dunn) has put it, the play “starts with the end and remains stuck there.” Euripides deftly (and consciously) plays around with the expectations of the audience, leaving Astyanax alive after his supposed death (he is usually killed on the night of the sack of Troy) and suggesting that Helen might be killed by Menelaus on two different occasions (even though, traditionally, we know that she should remain alive). It is as if the play makes a step forward only so that it can take a step back—a pretty unusual and daring strategy for an Ancient Greek writer.

But, then again, what kind of movement should one expect after an apocalyptic event such as the sack of Troy? What hope and what faith? Even the Greeks, as Cassandra suggests in her hallucinations, cannot be deemed victors of this ten-year war, their dead lying unburied on foreign ground, surrounded by strangers and far from their loved ones. As Hecuba and the Chorus realize at the end of the play—and as Euripides often likes to point out—the question of whether the gods exist is beside the point; the more important question is whether they care. And the answer, as depicted in the events of the Trojan Women, is bleak: they don’t, and they never have.

Trojan Women Sources

There are many translations of Trojan Women available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read E. P. Coleridge’s translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Gilbert Murray’s rhyming verse adaptation here.

See Also: Euripides, The Sack of Troy, Hecuba, Cassandra, Andromache, Helen

Trojan Women Video

Trojan Women Associations

Link/Cite Trojan Women Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Trojan Women". GreekMythology.com Website, 29 Nov. 2019, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Trojan_Women/trojan_women.html. Accessed 22 April 2024.