Helen

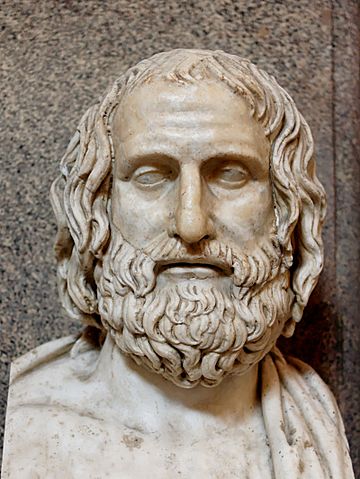

Helen by Euripides

First produced in 412 BC for the City Dionysia, Euripides’ Helen is a variant of a story first told in the Palinode by the Archaic lyric poet Stesichorus, according to whom Helen did not, in fact, go to Troy with Paris. Instead, she was substituted with a phantom by Hera, who ordered the real Helen to be taken away to Egypt, where she has been languishing for a decade now under the watchful eye of a lustful Egyptian king called Theoclymenus, son of the sea-god Proteus. Theoclymenus wants to marry Helen, but is unable to do so due to the fact that Helen is still legally married to Menelaus. However, soon after the fall of Troy, the greet Greek archer Teucer brings news to the real Helen (not knowing that it is her) that Menelaus is presumed dead and that she is hated by almost everyone for her part in the conflict. He leaves to find the prophetess Theonoe—Theoclymenus’ sister—to get some help, and, not much later, Menelaus appears on the coast, recently shipwrecked there along with the divine specter he believes is Helen. After a brief encounter with an Old Woman, Menelaus is surprised to happen upon a woman looking just like his wife. After hearing out her story and receiving news that the phantom Helen has disappeared, he is convinced that the Egyptian Helen is not lying, and the two spouses are joyfully reunited. They immediately turn to Theonoe for some help and start devising a plan how to leave Egypt. Once they have it all figured out, Helen goes to Theoclymenus and reveals to him that her husband Menelaus has died in the shipwreck and that she is now free to marry him. However, before that—as it befits a wife—she’d want a ship to scatter her husband’s remains at sea in accordance with Greek customs. Her demand is met, but the ship, as planned, is seized by Menelaus and his sailors who immediately steer it in the direction of Sparta. Theoclymenus tries to intervene, but Helen’s brothers, the Dioscuri, appear deus ex machina and forbid this.

Date and Historical Background

Helen was first produced in 412 BC in a trilogy together with the lost Andromeda and, according to some, Ion. The result of the competition is not known.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, the queen of Sparta and the wife of Menelaus

• Menelaus, Helen’s husband, king of Sparta

• Theonoe, daughter of Proteus and sister of Theoclymenus; prophetess

• Theoclymenus, son of Proteus and king of Egypt; brother of Theonoe

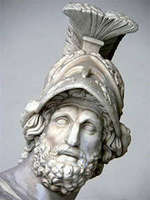

• Teucer, the most renowned Greek archer under Troy

• Old woman, gatekeeper of the palace

• Servant of Menelaus

• Messenger, servant of Theoclymenus

• The Dioscuri, Helen’s immortal brothers, sons of Zeus

• Chorus of captive Spartan women

Setting

The play is set in Egypt, before the palace of Theoclymenus and in the vicinity of the tomb of Proteus.

Summary of Helen

Prologue

As customary in Euripides, Helen opens with an introductory monologue by the protagonist which, in turn, begins with a genealogy. In this case, there are two of them: the first one recounts briefly the lineage of the Egyptian king Proteus, while the second one tells the backstory of Helen. Strikingly, we learn that the real Helen never left for Troy with Paris. Hera, she tells us, indignant at not defeating Aphrodite during the Judgement on Mount Ida, made “an airy nothing” of Helen’s marriage with Paris by giving to the son of king Priam an image “fashioned out of the sky” to look just like the real Helen. As for her, she was whisked away to Egypt by Hermes before the beginning of the Trojan War, and she has spent the ten years since lingering there and waiting for her husband Menelaus to save her. While Proteus was alive, she tells us, she felt safe; however, now that that “he is hidden in the dark earth,” his son, Theoclymenus, hunts after a marriage with her.

“Oh gods, what sight is here?” shouts the great Greek archer Teucer upon suddenly noticing Helen praying before the grave of Proteus. “I see the hateful deadly likeness of the woman who ruined me and all the Achaeans,” he goes on. “If I were not in a foreign land, you would have died by this well-aimed arrow as a reward for your likeness to the daughter of Zeus.” During the discussion that follows, Helen—who is unwilling to reveal herself just yet—learns from Teucer that she is hated by just about everyone for starting the Trojan War, and that her husband Menelaus is believed “to have disappeared with his wife” at sea during a tempest. Teucer, on the other hand, learns from Helen that it’s best for him to leave Egypt as soon as possible, because the local king “kills every visitor from Hellas that he catches.” Even though Teucer has come to Egypt (after being exiled from his native Salamis by his father) to consult the wise prophetess Theonoe how to reach Cyprus, he heeds to Helen’s advice, blessing her before leaving for having a heart unlike that of Helen even while sharing the same body.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

As Teucer departs, a Chorus of captive Greek women enters and starts singing responsively with Helen. It is a mourning song: firstly, for all the dead heroes under Troy—most notably, Menelaus—and secondly, for Helen herself who, though innocent, is wrongly and universally condemned. “What evil is not yours?” the Chorus sings. “What life have you not endured?”

First Episode

After hearing out the Chorus’ lament, Helen realizes that there’s really no reason for her left to go on living: her mother is dead (and she is thought of as her killer), her husband has died as well (and he has left this world thinking her a traitor), and a marriage awaits for her with a barbarian (who is about to find out that she is free). So, Helen vows to die instead. The Chorus suggests that she doesn’t do anything rush and irrational before consulting the wise Theonoe, “who knows all things,” and who might give her some valuable advice in these dire times. Helen agrees and they all go into the palace.

As soon as the doors close behind them, Menelaus appears before the grave of Proteus, and reveals that he has been recently cast on this shore by a tempest that has broken his ship into many pieces against the rocks. Not long ago a conqueror of Troy, now he is “a miserable shipwrecked sailor who has lost his friends” in an inhospitable and unknown land. Ashamed of his condition, he hasn’t made inquiries so far, but wearied away by his poverty, he decided to come to this palace (the owner of which he doesn’t know) as soon as he first saw it, because “sailors can hope to get something from wealthy homes.” Menelaus also reveals that he has hid “deep in a cave” his wife, Helen—the woman who had caused all of his troubles—and left some of his surviving friends to guard her. The gatekeeper of the palace, an Old Woman, answers Menelaus calls, and in a brief and rather comical conversation, tells him that the house belongs to the Egyptian royal family and that he is not welcomed there due to his Hellenic background. Especially not so at the moment, she adds, because Helen, the daughter of Zeus, is also inside the house discussing her fate with Theonoe. Menelaus can’t believe his ears, even less when he learns that Helen has been around ever since the beginning of the Trojan War. However, he laughs away his confusion after concluding that “there are probably many things in the wide world that have the same names, both cities and women.”

Menelaus’ confusion returns very soon, as Helen and the Chorus exit the palace before he can even cast off his doubts. Joyous at learning that Menelaus is not dead, neither Helen nor the Greek captives notices Menelaus before the gates. He does catch sight of Helen and barely believing his eyes, starts questioning her. “You seem to me very much like Helen, lady,” he says soon after. “And you seem to me like Menelaus,” she replies. Menelaus reveals that Helen is right, but no matter how hard Helen tries to explain that he has guessed her identity correctly as well—and that he has taken with him a phantom from Troy—Menelaus doesn’t believe her. On the contrary, in fact, he leaves her, believing that the gods have merely added one more misfortune to his numerous recent troubles. However, barely he has made a few steps, when a Servant of his arrives from the Cave and reveals to Menelaus that his wife “has disappeared, taken up into the folds of the unseen air.”

Realizing thus that the real Helen is the one he has just spoken with, Menelaus rushes back into her embrace. “I have found you,” he exclaims, “but I have many questions about those years; now I do not know what to begin with first.” During the lyrical reunion, Menelaus learns the whole truth from Helen. Overhearing the discussion and willing to take part in the joy, Menelaus’ servant joins in. Upon discovering from Menelaus that Helen was not “the arbitrator of all the trouble in Troy,” his servant replies with a striking question—“What are you saying? We suffered in vain for the sake of a cloud?”—and an ambiguous shriek: “How intricate and hard to trace out is the nature of the god!”

Afterward, he departs to tell the other surviving members of Menelaus’ troops the good (even if, strange) news, leaving Menelaus, Helen and the Chorus to discuss between them their next actions. Helen begs Menelaus to flee the land and save his life, but now that he has found her, he is unwilling to leave her no matter what that might mean. After failing to convince him, Helen offers another solution. “There is one hope, and only one, for our safety,” she says. “The king’s sister; she is called Theonoe and she knows everything… Perhaps we might persuade her by supplication not to tell her brother that you are here in this land.” If they fail to do this, then it is all but sure that Menelaus will be murdered and Helen will be forcefully given into marriage to Theoclymenus; however, if they succeed, they might even leave Egypt peacefully.

Even before the two reach an agreement, Theonoe comes out of the house, attended by handmaidens carrying torches. Helen and Menelaus fall on their knees and plead the righteousness of their cause before the prophetess in two separate monologues. Theonoe decides in their favor, judging it more just to side with the promise of her father, Proteus, to safeguard Helen than with Theoclymenus’ unjust desires to wed a married woman. “My nature and my inclination lean towards piety,” she responds after hearing out her guests. “And I respect myself, so I would not defile my father's fame, or gratify my brother at the cost of seeming infamous.”

After Theonoe and her attendants enter the palace, Menelaus starts devising escape-plans. Helen dubs them impractical and offers an alternative revolving around a mock funeral at sea for the supposedly “dead” Menelaus. Menelaus agrees and withdraws, and Helen enters the palace, praying to Hera and Aphrodite for support.

In the first stasimon after the longest episode in Greek tragedy, the Chorus remembers the brave soldiers who will never realize that they have died in the Trojan War because of “Hera's holy phantom.” What kind of gods are those who have allowed such a thing?

Second Episode

As planned, just as soon as Theoclymenus comes back from his hunting trip, Helen, clad in mourning clothes, exits his palace and announces that a Greek messenger has arrived to reveal to her that her husband has died and lies unburied at sea. She asks for a permission to carry out his funeral rites in accordance with Greek customs and “take out of harbor to the sea all that is the dead man's due.” Theoclymenus is suspicious that Helen needs a ship to burry Menelaus, but is convinced once the supposed messenger (actually, Menelaus) arrives and tells him that the custom is such “so that the waves may not wash pollution back ashore.” He tries to persuade the “messenger” to perform the burial rites without Helen, but Menelaus replies that it is a task that “belongs to mother, or wife, or children,” and that “piety demands that the dead be not robbed of their due.” Theoclymenus eventually agrees to all of Helen’s requests, especially in view of her promise that she’d marry him once the burial is done.

As the three enter the palace, the Chorus sings the so-called “Mountain Mother” ode, telling the beautiful but fairly unconnected (and, thus, possibly even interpolated) story of Demeter, whom Aphrodite, the Graces, and the Muses can only make smile “with song and dance.”

Third Episode

Helen comes out of the palace alone and reveals to the Chorus that Theonoe has kept her word and told her brother that Menelaus “was not alive, but dead and buried.” Theoclymenus and Menelaus appear soon after, and the former attempts yet again to persuade Helen to remain ashore, now afraid that she might commit suicide once at sea. However, eventually he concedes to all of Helen’s wishes and orders an attendant to give Helen and the Greek messenger “a Sidonian ship of fifty oars, and rowers also.” Afterward, he retreats to his palace, and Menelaus, Helen and their train of attendants head toward the port.

In the third stasimon, the Chorus envisions the return of their queen to Sparta and sings of the ritual dances they will all dance once back in their homeland. They summon the Dioscuri—Zeus’ sons and Helen’s brothers—to cast away from their sister her ill-fame, for neither she ever went to Troy nor she married a barbarian.

Exodos (Exit Song)

As Theoclymenus comes out of his palace, a Messenger reveals to him the takeover of his ship and the killing of all Egyptian sailors by Menelaus, “the one that came with the news of his own death.” Theoclymenus is furious—especially at his sister Theonoe for lying to him. He vows to avenge himself upon her so that she never deceives another man by her oracles. He is delayed in this action by the leader of the Chorus who says that Theoclymenus might kill Theonoe but only over her dead body. Suddenly, out of the blue, the Dioscuri appear and reveal that this was all part of Zeus’ plan: Helen’s innocence, the phantom initiating the Trojan War, her escape with Menelaus from Egypt, and their blessed future ahead. Theoclymenus is appeased by their words, and the Chorus, in the last verses of the play, praises the gods for finding a way out even when this seemed impossible.

A Brief Analysis

Just like Iphigenia in Tauris, Euripides’ Helen is set in a non-Greek exotic setting, features an intricately plotted and thrilling escape, and it has a happy ending. It shares most of these aspects with Ion as well, and some of them with Orestes and the lost Andromeda—because of which these four plays are usually grouped together under the title “romantic tragedies.” Even so, Helen seems to be the least tragic of the bunch: not merely because of the happy ending, but also because “there is little potential” for any kind of tragic outcome during the entire play. In fact, it’s quite the opposite: most of the events that happen in the play seem to retroactively erase the tragic character of numerous past events, most strikingly through the unexpected conversion of Helen from a universally hated character to a sympathetic heroine. “What Euripides has done,” sum up the transformation beautifully Ian Storey and Arlene Allan, “is to change Helen into Penelope, waiting patiently (and chastely) for her husband to rescue her.” However, even though this exonerates Helen from any wrongdoings and sets the tone for a heart-breaking reunion scene within the play, the transformation does have some possibly unintended retroactive consequences. If the Helen for whom the Greeks fought under Troy is just an illusion—asks justly the Messenger—then doesn’t that mean that the Trojan War was basically for nothing?

Helen Sources

There are many translations of Helen available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read E. P. Coleridge’s translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Arthur S. Way blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Helen, Menelaus, Teucer, Euripides

Helen Video

Link/Cite Helen Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Helen". GreekMythology.com Website, 30 Jan. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Helen/helen.html. Accessed 24 April 2024.