Alcestis

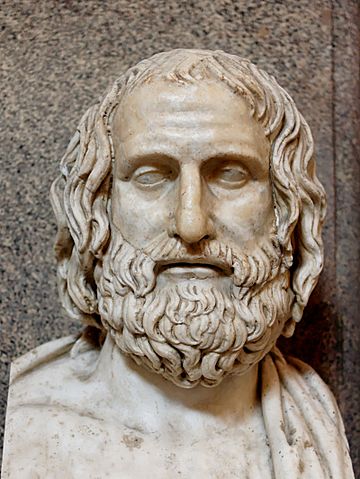

Alcestis by Euripides

First performed at the City Dionysia festival in 438 BC, Alcestis is the oldest surviving play by Euripides. Curiously, even though it was presented as the final part of a tetralogy, it is not a satyr play—but it is neither a tragedy as well. The so-called “problem play” is set in Pherae, Thessaly, on the day that Queen Alcestis is scheduled to die in place of her husband, King Admetus, who, having granted hospitality to Apollo long before, has now earned his right to live past the assigned time of his death. However, the deal includes someone dying in his stead, and the only one who has agreed to this is his loving wife, Alcestis. She has only one wish: that Admetus not marry again. The king promises his wife not only this but also to banish all joy from his palace forevermore. However, soon after the death of Alcestis, Admetus’ friend, the great hero Heracles, arrives at his palace, expecting generosity and a proper welcome. Despite his promise to Alcestis and the objections of the old men of Pherae (comprising the Chorus), Admetus receives Heracles, keeping secret the death of his wife. After a vicious exchange between Admetus and his father Pheres—whom the king had expected to die in his place—the funeral procession leaves, Admetus with it. In a while, the already drunken Heracles emerges from the palace and learns the truth about Alcestis from a servant; embarrassed at his behavior, Heracles leaves the palace. Admetus returns from the funeral, sad and regretful that he has accepted Apollo’s favor: even though he is still alive, he is alive without his Alcestis, who must be much better off in death than he is in life. Amid Admetus’ sorrow, Heracles returns, leading beside him a veiled woman, whom he surrenders to the hesitant and unenthusiastic Admetus. It turns out that the woman is none other than Alcestis: Heracles, we learn, wrestled Admetus’ wife away from the hands of Death to make amends for his conduct and as a favor to his generous host.

Date and Historical Background

Even though Euripides had been writing plays for almost two decades before Alcestis was first produced in 438 BC, this is the oldest surviving play in his oeuvre. None of the other three plays it was presented with—Cretan Women, Alcmaeon in Psophis, and Telephus—have survived. Euripides finished second at the City Dionysia festival of that year behind Sophocles who won the first prize with an unknown tetralogy.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Apollo

• Admetus, the king of Pherae, Thessaly

• Alcestis, the queen, wife of Admetus

• Eumelus, their child

• Pheres, Admetus’ father

• Heracles

• Death

• A manservant

• A maidservant

• Chorus of old men from Pherae

Setting

The play is set outside the palace of Admetus at Pherae, Thessaly. The center of the scene is a portico with a large double-door and columns. The women’s quarters are to the left, and the guest rooms to the right.

Summary of Alcestis

Prologue

At the beginning of Alcestis, Apollo, all in white, comes out from the palace of Admetus at Pherae, the golden bow in his hand, a quiver on his back. In the opening monologue, he introduces the audience to the events that have led up to the moment. Long ago, Apollo tells us, as a direct consequence of him slaying “the Cyclopes who forged Zeus's fire,” he was punished by the King of Olympus to be a herdsman at this very palace to King Admetus, who treated him as kindly as possible. “I am myself godly,” Apollo says, “and in Admetus, son of Pheres, I found a godly man.” To repay Admetus, the god tricked the Fates, who promised him that his former host would not die on the day he is destined to, provided that he finds someone else’s corpse to give in exchange to “the powers below.” The only one who agreed to this kind of deal was Admetus’ wife, Alcestis, and today is the day of her death.

Appropriately, it is also the day that Death arrives at the palace, dressed in black and with a sword in his hand. He is not happy that Apollo has robbed him of Admetus’ corpse and is furious to see the god here, fearing that he plans to trick him out of Alcestis’ body as well. “Is there any way Alcestis might reach old age?” Apollo asks kindly. “There is none,” replies Death. “I too, you must know, get pleasure from my office.” After an unsuccessful attempt to persuade him to postpone the death of Admetus’ wife, Apollo leaves, but not before prophesying the arrival of a man who “shall take the woman from [Death] by force.” It is evident that Apollo has a pretty specific hero in mind, Heracles, who is “coming to the house of Pheres sent by Eurystheus to fetch the horses and chariot from the wintry land of Thrace.”

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The chorus, which consists of fifteen old men of Pherae, enters the orchestra and divides into two semi-choruses. Confused by the silence and the absence of groans and cries, the men ask each other whether Alcestis, “the best of wives to her husband,” is dead or still alive. They know this is the fated day, but they secretly hope for some miracle or any kind of good news. Noticing a maidservant stepping out of the palace, they realize that they are about to find out.

First Episode

“I would like to know whether the queen yet lives or has died,” the leader of the Chorus comes up to the maidservant. “You might call her both living and dead,” answers she ambiguously, further clarifying that she is “already sinking and on the point of death.” “Let her know then that she will die glorious and the noblest woman by far under the sun,” sighs the Chorus-Leader. “Noblest indeed!” exclaims the maidservant before going into a lengthy description of Alcestis’ touching preparation for the inevitable: her own death. After bringing her report to a close, the maidservant retreats inside the palace to inform Admetus of the arrival of the Chorus.

Left alone, in the first stasimon of the play, the Chorus turns to Apollo for help, hoping that the god would be able to find some miraculous cure just like he did when Admetus’ life was in danger. The prayer of the Chorus is interrupted by Admetus and Alcestis who ceremoniously step out of the palace, followed by their two children.

Second Episode

Haunted by visions of Charon dragging her to Hades, Alcestis starts lamenting her own death even though still alive. Heartbreakingly, she tells her children that they don’t have a mother anymore, and asks her husband that, in return for her sacrifice, he never marries again. She’s doing this for her children, after all (she doesn’t want them to remain without a father), and, in her experience, even vipers are kinder than stepmothers.

Admetus agrees to this wholeheartedly: “While you lived you were my wife, and in death, you alone will bear that title,” he says. “No Thessalian bride will ever speak to me in place of you, none is of so noble parentage or so beautiful as that. And of children I have enough. I pray to the gods that I may reap the benefit of them, as I have not of you. I shall mourn you not a year only but as long as my life shall last.” Even more: Admetus promises to “put an end to revels and the company of banqueters and to the garlands and music” which once filled his halls with joy. “I shall never touch the lyre, or lift my heart in song to the Libyan pipe. For you have taken all the joy from my life,” he concludes. Soon after Admetus utters his promise, Alcestis dies, and the couple’s son Eumelus bursts into a moving dirge, tears streaming down his face.

The mood is echoed in the Chorus’ second stasimon, both an elegy for the death of Alcestis, and an ode to her nobleness and goodness. “If your husband should take a new bride,” they warn, “he will be hateful in my eyes as in those of your children…”

Third Episode

The Chorus has barely finished its song when Heracles, an old friend of Admetus, arrives at the palace. Unaware of the tragedy which has just taken place, he asks for a place to stay, which Admetus, in spite of the Chorus’ objections, grants him, without uttering even a word related to his misfortune. “He would never have consented to enter the house if he had known anything of my sorrow,” says Admetus to the old men of Pherae. “My house does not know how to reject or dishonor guests.”

Though still hesitant whether Admetus has made the right choice (especially with regards to his promise to Alcestis to banish all joy and merrymaking from his palace), in the third stasimon, the Chorus praises Admetus’ seemingly boundless hospitality. “Even now,” they sing, “he has received a guest though his own eyes were still wet, weeping for the loss of his dear wife so recently perished in his house…”

Fourth Episode

Amid the preparations for the funeral procession, Admetus’ father, Pheres, comes out of the palace to share in the trouble of his son and offer his help. Admetus, however, would have none of it: Pheres was never invited to Alcestis’ funeral, and, in his eyes, he should have never come, for it is his fault that she is dead. “When you were put to the test you showed your true nature,” Admetus says to Pheres, “and I do not count myself as your son. You are, you know, truly superlative in cowardice; for though you are so old and have come to the end of your life, yet you refused and had not the courage to die for your own son, but you and your wife let this woman, who was no blood relative, do so.” Insulted, Pheres replies that he was never obliged to die for anyone, let alone for someone he has dedicated his whole life to anyway, begetting him and raising him to become the master of his own house. Moreover, he adds, it is not his fault that Alcestis is dead, but Admetus’, for he could have accepted his allotted hour and saved her life at any hour. An even nastier exchange follows, which culminates with Admetus chasing away his father from the funeral procession and expressing his wish that he and his wife (Admetus’ mother) die a painful death as soon as possible.

As the funeral procession moves off, a manservant comes out of the palace and complains of Heracles’ behavior, claiming that, in all his life, he has never welcomed a worse guest than this one. Garlanded and visibly drunk, Heracles interrupts the servant’s monologue and chides him for his gloomy face. During the discussion which follows the servant snaps and tells Heracles the truth in spite of Admetus’ orders. Embarrassed by his behavior and overwhelmed by the nobleness of his magnanimous host, Heracles expresses his determination to make amends, even if that means ambushing Death himself and fighting him for the life of Alcestis.

As Heracles leaves, Admetus and the Chorus return to the palace, lamenting not only the death of Alcestis but also the fate of the king, whose pain is so unbearable that he craves for death. “Why did you keep me from throwing myself into the open grave and lying there dead with her, the best of women?” Admetus asks the Chorus weepingly.

In the fourth stasimon, the Chorus expresses its conviction that Alcestis will be honored as much as a goddess by future generations, her funeral mound “an object of reverence to the wayfarer.” “This woman died in the stead of her husband, and now she is a blessed divinity. Hail, Lady, and grant us your blessing!” With such words Alcestis will be addressed by others, according to the Chorus.

Exodos (Exit Song)

Carrying a veiled woman with him, Heracles returns to the palace once again, and, in a friendly manner, reprimands Admetus for not being completely honest with him. He says that he doesn’t want to be a nuisance anymore, but he does have one final request. Namely, while he is away on his labors, Admetus to take care of the woman he has brought with him, for he has won her in a fearsome competition. In return for his favor, the woman will serve to Admetus until Heracles’ return.

Even so, the King is not interested in the deal and agrees to accept the woman only after much persuasion and out of respect to Heracles. However, when he does so and lifts her veil, Admetus cannot believe his eyes: the woman is none other than Alcestis, won by Heracles from the sure clutch of Death. “You are not yet allowed to hear her speak to you,” says Heracles on going away, “not until she becomes purified in the sight of the nether gods when the third day comes.” Admetus blesses Heracles and asks him to stay some more, and the hero promises to do that—but sometime in the future, possibly on his way back.

“Many things the gods accomplish against our expectation,” sings the Chorus in the final verses of the play. “What men expect is not brought to pass, but a god finds a way to achieve the unexpected. Such was the outcome of this story.”

A Brief Analysis

Possibly “the principal problem” of Alcestis is the nature of the play. Since it was undoubtedly performed as fourth in a tetralogy, it should be a satyr-play, but there are no satyrs in it, and, for the most part, it resembles a tragedy. Could it be some kind of a Euripidean experiment in form and genre? Even the Greek critics seem to have been baffled by the nature of Alcestis: “the play is somewhat satyric in character," says an ancient hypothesis (“introduction,” “argument”) to the play.

As for its content, Alcestis is interesting for a number of reasons, mostly because it is unclear what Euripides wanted to present with it. If it is a tragedy with a happy ending, who is the protagonist, the ostensibly tragic character of the play? If it is Admetus, has he deserved the happy ending? If it is Alcestis, is it a happy ending? What kind of a marriage awaits the two lovers, now that they’ve found out that one of them was ready to sacrifice for the other, and the other couldn’t keep a promise given on a deathbed for more than a few moments?

On the other hand, if it is a satyr-play, should we bother with questions such as these? Could it be written merely as a light (even if not, comic) relief for the audience after three sad stories? If so, why the tragic tone throughout, why so many heartbreaking lamentations by Alcestis, Admetus, and even Eumelus, a child?

Finally, if it is a form in between these two, could Euripides be doing here something akin to Shakespeare in his romances, painting, on the surface, a magical world in which virtue is bound to be rewarded even against the rules of the physical world, while simultaneously questioning the nature of our real-world happiness through the very fact that the play is modeled as a fairytale? Chances are, we’ll never find out. But that shouldn’t stop us from pondering these questions: it is a worthy endeavor in itself.

Alcestis Sources

There are many translations of Alcestis available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read David Kovacs’ translation for Loeb Classical Library here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Gilbert Murray’s rhyming verse adaptation here.

See Also: Euripides, Alcestis, Admetus, Apollo

Alcestis Video

Link/Cite Alcestis Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Alcestis". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Euripides/Alcestis/alcestis.html. Accessed 20 April 2024.