Peace

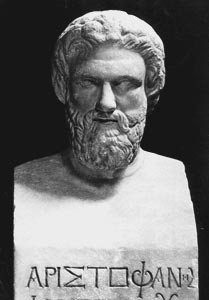

Peace by Aristophanes

First produced in 421 BC – just two weeks before a peace treaty that ended the first half of the Peloponnesian War – Peace is Aristophanes’ most joyous comedy. Its protagonist is a countryman named Trygaeus (from trugan which in Greek means “to harvest fruit,” particularly grape), who, angered by the long war, has decided to ask Zeus why he is allowing to continue it. So, in a manner mimicking that of Bellerophon, Trygaeus flies up to Olympus – but not on Pegasus or some other majestic steed, but on a gigantic dung-beetle. To his surprise, he finds that the gods, annoyed with the Greeks for refusing to make peace, have deserted their mountain, leaving personified War (and his slave Uproar) in charge. War has imprisoned Peace in a cave and intends to rule for eternity. The only god who has remained on Olympus is Hermes, who is looking after the other gods’ households. With his help and the assistance of some twenty farmers (the Chorus), Trygaeus is able to liberate Peace out of her confinement and thus put an end to War’s reign. Trygaeus is now sent back to earth in the company of Peace’s handmaids: Harvest (or Opora, in Greek) and Festival (Theoria). The latter ends up in the hands of the Athenian Council (the Boule), while the former marries Trygaeus in the last part of the play. In the meantime, Trygaeus has to deal with a few war profiteers: a well-known oracle-monger named Hierocles and several arms merchants. His wedding is afterward celebrated with a marvelous feast, at which two boys sing songs – one a celebration of war by Homer, and the other a celebration of an act of cowardice by Archilochus. Trygaeus is not that fond of either one.

Date and Historical Background

In 423 BC, Athens agreed to a one-year truce with Sparta, but soon afterwards, Cleon convinced the Athenians to restart the war in order to recover the city of Amphipolis, conquered by the Spartan general Brasidas the year before. Fought in 422 BC, the Battle of Amphipolis – in which the philosopher Socrates might have also participated – resulted in a disastrous defeat for Athens: it lost a fourth of its army of 2,000 men, and there were only 8 Spartan casualties. Among these eight, however, was the victorious Spartan commander himself, Brasidas. Athens, too, lost its commanding general: Cleon, Aristophanes’ arch-nemesis.

The death of these two men created favorable conditions for a new peace treaty. The discussions between Athens and Sparta were already in an advanced phase when Peace was first performed at the City Dionysia of 421 BC. Just two weeks later, seventeen representatives from each side involved in the Peloponnesian War swore an oath of peace, which would later become known as the Peace of Nicias. Even though it obliged all sides to withhold from military activity for the next half a century, the treaty would be broken not long after and formally abandoned in 414 BC.

Peace won Aristophanes the second prize at the joyous festival of 421 BC. The victory went to Aristophanes’ greatest rival, Eupolis, for his play The Flatterers. Leucon finished third with The Phratry.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Trygaeus, a countryman

• Two slaves of Trygaeus

• Daughters of Trygaeus

• Hermes, the messenger of the gods

• War, a personification

• Uproar, slave to War, also a personification

• Hierocles, an oracle-monger

• An armorer

• A sickle-maker

• A crest-maker

• First boy, son of Lamachus

• Second boy, son of Cleonymus

• Chorus of farmers

Setting

Notoriously difficult to produce, Aristophanes’ Peace is mostly set outside a house in Athens, but a large part of it is also set in the heavens.

Summary of Peace

Prologue

In front of a stable of an Athenian farmer, two slaves are breathlessly kneading cakes of excrement and feeding them to a gigantic dung-beetle kept by their master inside the stable. One of them turns to the audience and explains to them that the scene is not “an allusion to Cleon, who so shamelessly feeds on filth all by himself” – but a product of his master’s madness. Apparently, just like Dicaeopolis in The Acharnians (Aristophanes’ first peace-play), he has despaired for years of obtaining peace through ordinary legislative channels and, seeing no advancements in his pursuit, has now resolved to fly up to none other than Zeus himself and demand from him to put an end to the Peloponnesian War. And why should a dung-beetle – of all flying creatures – help him? The slaves don’t know: they just know that he treats the insect as though it were a horse, saying, “Oh! my little Pegasus, my noble aerial steed, may your wings soon bear me straight to Zeus!” Unlike the slaves, the spectators should have guessed why Aristophanes chose a dung-beetle instead of a horse: the opening scene serves as a parody of the now-lost Bellerophon by Euripides, Aristophanes’ least favorite of the great tragedians.

The slaves don’t even get a chance to finish explaining the situation to the spectators when Trygaeus appears above their heads mounted on the dung-beetle as if on a horseback. “Where are you going?” asks one of the slaves. “To visit Zeus,” answers Trygaeus, and “ask him what he reckons to do for all Greeks.” “And if he doesn’t tell you?” “I shall pursue him at law as a traitor who sells Greece to the Persians.” Interpreting this as a sure sign of madness, the slave calls upon Trygaeus’ daughters to see their father for the last time, but Trygaeus explains them that he is doing this for them: the war has ravished their household and only by talking Zeus into declaring peace he can make amends for not being able to earn enough money and feed them properly. “But why a beetle?” asks one of the daughters. Trygaeus offers two reasons: first, Aesop says in his fables that “they alone can fly to the abode of the Immortals;” and second, a dung-beetle is much more economical than a horse or an eagle.

After negotiating his journey with his slaves and daughters with success, Trygaeus soars heavenward and, soon after, reaches the palace of Zeus. He dismounts from the beetle and knocks at the door full of expectations, but is in for a rude surprise: Hermes is the only one inside. The messenger of the gods explains to Trygaeus that the gods have moved to the furthest end of the dome of heaven and have left him to watch over what has remained of “the furniture, the little pots and pans, the bits of chairs and tables, and odd wine-jars...” “But why have the others moved away?” asks Trygaeus, stunned beyond belief. “Because of their wrath against the Greeks,” answers Hermes. “They have located War in the house they occupied themselves and have given him full power to do with you exactly as he pleases; then they went as high up as ever they could, so as to see no more of your fights and to hear no more of your prayers.”

Quite expectedly, the first act of the new master of heaven has been to cast Peace into a deep pit and then to pile heaps of stones over her, so that the Greeks may never be able to pull her out again. To make matters worse, just the previous evening, War brought along a huge mortar, with which he intends to “pound up all the cities of Greece” and turn them into a paste. No sooner has Hermes reported this than War himself appears, carrying the said mortar. “Oh! mortals, mortals, wretched mortals, how your jaws will snap!” says War joyously in his first utterance, as Hermes leaves and Trygaeus hides away. Quite immediately after, he starts tossing different Athenian cities in the mortar, each represented by their most noted product: leeks for Prasiae, garlic for Megara, cheese for Sicily. Fortunately for the Greek cities, War doesn’t have a pestle to start squashing them so he sends his slave Uproar to fetch one from Athens or Sparta. Uproar quickly returns from his trip to earth with empty hands and an information that both Athens and Sparta have lost their pestles (meaning, both Cleon and Brasidas, the most hawkish apologists of war on both sides, have died). Seeing no other option, War retreats in Zeus’ palace to make his own pestle. With the horrible fate of Greece momentarily averted, Trygaeus emerges from his hiding-place. “Now, oh Greeks!” he shouts. “Now is the moment when freed of quarrels and fighting, we should rescue sweet Peace and draw her out of this pit, before War’s pestle prevents us. Come, laborers, merchants, workmen, artisans, strangers, whether you be domiciled or not, islanders – come here, Greeks of all countries, come hurrying here with picks and levers and ropes! This is the moment to drain a cup in honor of the Good Genius.”

Parodos (Entrance Song)

A Chorus of laborers and farmers from various Greek states now enters, but its members are so elated under the circumstances that they cannot focus on the task and hand and, instead, start dancing and singing about “the blessed day” when peace will come. As soon as Trygaeus manages to restore quiet and ask the laborers to help him remove the stones under which Peace is buried, Hermes returns, scolding the Greeks for the audacity of their plan.

Episodes

“Don't you know that Zeus has decreed death for him who is caught exhuming Peace?” Hermes asks Trygaeus, and threatens to call Zeus to intervene. The Chorus begs him not to do this and have mercy at their misfortunes. Trygaeus goes a step further: he claims that this is all part of a plot devised by the Sun and the Moon to deliver Greece into the hands of barbarians, because they worship them more. Fearing that he might thus lose all Greek sacrifices, Hermes is persuaded to join the just cause of freeing Peace and restoring its rule.

The task proves pretty difficult, because the Chorus consists of citizens of many Greek city-states, and each of them seems to have different interests and methods. Some of the Greeks are pulling one way and some another. The Boeotians are only pretending to help but they really aren’t; the Argives laugh at all the others while actually profiting from their troubles; the Megarians are too underfed to be of much help; the Laconians and the Athenians do their best to help – but, in each case, it seems that only the farmers are doing the hard work. Anyway, Peace is eventually dragged out of the pit, along with Harvest (Opora) and Festival (Theoria). Everybody is thrilled to see them, and suddenly the differences between the different Greek city-states seem a thing of the past. Seeing how beautiful Peace is, the farmers start wondering how could they have lost her. “But where was she then,” they ask Hermes, “all the long time she spent away from us?”

“The start of our misfortunes,” answers them the divine messenger, “was the exile of Phidias; Pericles feared he might share his ill-luck, he mistrusted your peevish nature and, to prevent all danger to himself, he threw out that little spark, the Megarian decree, set the city aflame, and blew up the conflagration with a hurricane of war, so that the smoke drew tears from all Greeks both here and over there. At the very outset of this fire our vines were a-crackle, our casks knocked together; it was beyond the power of any man to stop the disaster, and Peace disappeared.” Then, he goes on, no matter how many times Peace tried to come back, war profiteers led by the tanner Cleon voted against her in the Athenian Assembly. “They grew rich,” he concludes, “while you, alas! you could only see that Greece was going to ruin. It was the tanner who was the author of all this woe.”

Trygaeus apologizes to Peace on behalf of all of his countrymen, and updates her with the latest theater gossip. Though live and well, Sophocles – apparently – has become as corrupt as Simonides, and the great comedian Cratinus has died “of a swoon: he could not bear the shock of seeing one of his casks full of wine broken.” This is where the brief discussion between Trygaeus and Peace (voiced by Hermes) ends, and the moment when Trygaeus leaves for Athens, taking Harvest and Festival back with him. He plans to give the latter to the Athenian Council – and marry the former. As Trygaeus flies down to Earth with Harvest and Festival, the Chorus, left alone, steps forward and addresses the audience in a conventional parabasis.

First Parabasis

As usual, the parabasis begins with a few praises addressed by the author to himself. “Oh Muse,” the Chorus sings, “if it be right to esteem the most honest and illustrious of our comic writers at his proper value, permit our poet to say that he thinks he has deserved a glorious renown.” In addition to begging the Muse to bring Peace and drive the war from their city, they also request from her to refuse a few tragic poets admission to their celebrations and revels, presumably because they were in favor of continuing the war.

This seems a good place as any to note that the parabasis is incomplete. It also gives the impression of being hurriedly written, because a few of its lines are taken word for word from the parabasis of The Wasps. The fact that “indications of hasty composition are found nowhere else in the play” has led some scholars to suggest that “the parabases of most of the comedies were written last, after all the rest had been finished, and were thus regarded by the poet as something separate and independent” (Eugene O’Neill Jr.).

Episodes

At the conclusion of the parabasis, Trygaeus comes back to the stage, limping painfully, and accompanied by Harvest and Festival. “Ah! it's a rough job getting to the gods!” he complains to the audience. “My legs are as good as broken through it. And how small you were, to be sure, when seen from heaven! you had all the appearance too of being great rascals; but seen close, you look even worse.” As this joke demonstrates, this is no time for complaints, but for a joyous celebration, for which Trygaeus immediately sets about preparing. He sends Harvest into his house to be bathed and dressed for the wedding, and presents Festival to the Athenian Council. Afterward, Trygaeus starts barbecuing the meat. In consultation with the Chorus, they symbolically choose to sacrifice a sheep, not only because “that’s the Ionic form of the word war,” but because, from now on, they “shall all be lambs one toward the other.” The fragrance attracts Hierocles, a well-known oracle-monger, whose ominous prophecies about the impossibility of ending the war are laughed off by Trygaeus. The tone of the play suggests that this is a genuine ridicule, but unfortunately, Aristophanes couldn’t have realized that Hierocles’ prophecies were much sounder than anyone at the time could have realized.

Second Parabasis

After Hierocles is driven off with blows and strikes, the Chorus is left alone for a brief second parabasis, which he uses to extol praise upon Peace and everything this goddess brings, singing lovingly of winter evenings spent in front of a kitchen fire and angrily of officers who took away these memories from them.

Episodes

Followed by his slave, Trygaeus comes out of his house and happily greets the guests at his nuptial feast. One of them, a sickle-maker, presents him with many of his products as a wedding gift for bringing back peace and, with it, prosperity to his business. He is followed by a group of war profiteers – an armorer, as well as makers of crests, trumpets, helmets, lances and breastplates. The armorer speaks on behalf of the group and blames Trygaeus for ruining them utterly: their products are worthless in a time of peace. Trygaeus gives them ideas on how to make them worthwhile (for example, turning the helmet crests into dusters), but ultimately refuses to buy them. As the munitions-makers all depart, some young boys enter. Among them are the sons of the Athenian generals Lamachus and Cleonymus, the former famous for his bravery, the latter for his cowardice. Appropriately, Lamachus’ boy sings a Homeric war son, and Cleonymus’ son a song by Archilochus celebrating cowardice. Trygaeus is impressed with neither and goes into the house.

Exodos (Exit Song)

The Chorus starts dancing and celebrating the wedding between their friend and Harvest. Followed by torch-bearing slaves, the two come out of the house at the end of the play, and everybody sings songs of joy and praise to Hymenaeus, the god of marital happiness.

A Brief Analysis

Peace is the simplest and most loosely structured comedy of the eleven by Aristophanes that have reached us. It is, at least in one respect, unique among his plays. As Alan Sommerstein writes, unlike a typical Aristophanic comedy – whose plot resolves, in a comic fantasy, something wrong with the current state of Athens – Peace merely depicts a different, more humorous etiology of a real-life solution to an all but past societal problem. In other words, while other plays by Aristophanes use fantasy to try to inspire change in the real world, Peace merely explores a “wrong” (the Peloponnesian War) that is on the point of being set right in reality itself.

Produced just two weeks before the Fifty-Year Peace between the Athenians and Spartans, it “reflects not so much the actual treaty but the expectation and good feelings that must have been in the air” (Storey and Allan). In his other peace plays (The Acharnians and Lysistrata), Aristophanes has someone to criticize, ridicule and debate against. Not in Peace: not only all enemies (War, Uproar) are personifications, there is also no formal agon (contest) in the comedy: who would speak for War when Peace was imminent? – ask rightly Storey and Alan. Even so, Aristophanes still has a few past scores to settle, so he is not beyond attacking Pericles and Cleon for bringing the war to Athens – even though both of them were dead at the time, the second one dying only recently.

“A comedy of high exuberance and sheer good spirits,” Peace is yet another Aristophanic call for a return to “the golden days of yore.” The atmosphere in the play is idyllic, and dominated by images of smells and odor which move from disgusting (the smell of the dung on which the beetle feeds) to divine (the ambrosial scent of the goddess and her handmaids) to domestic (the aroma of food cooking and the bouquet of good wines). Aristophanes makes a case here for a totally rural Athens and associates country life with fertility, abundance and happiness (Claudia N. Fernández). There are a few fragments that have survived of a second Peace, but it is unknown whether this is a reworking of this comedy or a completely new play.

Sources

There are a few translations of Peace available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read an anonymous translation for the Athenian Society edited by Eugene O'Neill, Jr. here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Benjamin B. Rogers verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, Sparta, The Acharnians, Lysistrata

Peace Video

Peace Associations

Link/Cite Peace Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Peace". GreekMythology.com Website, 03 Sep. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/Peace/peace.html. Accessed 19 April 2024.