The Birds

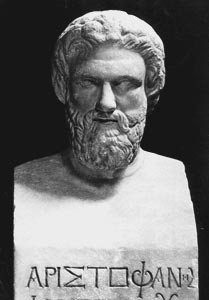

The Birds by Aristophanes

First performed in 414 BC at the City Dionysia (where it won the second prize), The Birds is the longest of Aristophanes’ surviving comedies, and perhaps the most acclaimed one. A “perfectly realized fantasy,” the play is unique among Aristophanes’ works in that it includes very few references to Athenian politics and two unconventional parabases. Peisetaerus (meaning “Persuader of his Comrades”) and Euelpides (“Son of Good Hope”) – two men fed up with the politics and law-courts of Athens – have fled the city and are in search of Tereus, who has, according to legend, turned into a hoopoe sometime in the past. They believe that he might help them find a better life somewhere in the clouds. Through his servant, the Footbird, the two do reach Tereus and he is sympathetic to their plight. During the discussion with him, Peisetaerus comes up with a magnificent idea: to found a city in the clouds. He realizes that if the birds just stop flying around and instead use their time to build an empire in the heavens, they might become masters of the universe. They should be able to thus both rule the humans from above and – by intercepting their sacrifices to the gods – starve the Olympians into submission. After concocting a story that the birds had been the rulers of the universe once, Peisetaerus manages to persuade a Chorus of various birds they deserve to rule it again. Soon enough, a new city is founded: Cloud-cuckoo-land. Since it becomes a thorn in the eye of both humans and gods, the birds now have to deal with several intruders, including a father-beater, a poet, an informer and the goddess Iris. They deal with them all, and are finally paid a visit by Prometheus who discloses two secrets to Peisetaerus: first, that the gods are in a bad situation and are about to send an embassy to Cloud-cuckoo-land, and, second, that Peisetaerus should demand Basileia (“Sovereignty”) for his bride as part of the peace terms. Olympus sends three unsophisticated gods (Poseidon, Heracles, and Triballus, a barbarian deity) as its delegates, which turns out to be a mistake, because Peisetaerus easily outsmarts Heracles who forces Triballus to agree with him, thus outvoting the suspicious Poseidon. The result: Olympus’ delegates agree to Peisetaerus’ conditions, and he is proclaimed the new ruler of heavens.

Date and Historical Background

Between 425 and 421 BC, Aristophanes probably wrote no more than five plays – all of which we can read today. However, after the production of Peace there followed six years during which his literary activity (if any) is lost to us. Then, in 414 BC, he produced two plays: the lost Amphiaraus at the Lenaean festival, and The Birds at the City Dionysia. The longest (over 1,700 lines) and, by far, the most lyrical of Aristophanes’ eleven surviving plays, The Birds won the second prize in the competition. In retrospect, it seems to suggest a shift in Aristophanes’ interests, since it is the first extant play which explores a Utopian theme, subject which will dominate most of Aristophanes’ later work. Even though the play was staged very soon after the commencement of the Sicilian expedition (an Athenian military expedition to Sicily which would end with a devastating defeat), the play, curiously, doesn’t even mention the Peloponnesian War. This has prompted many critics to try to find indirect allusions to Athenian politics, but, in general, The Birds defies interpretation of this sort and could be just “an escapist entertainment.”

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Peisetaerus, an Athenian citizen

• Euelpides, an Athenian citizen

• The Footbird, servant to the Hoopoe

• The Hoopoe, formerly Tereus, an Athenian prince

• Chorus of various types birds

• A priest, masked as a bird

• A poet

• An oracle-monger

• Meton, a famous astronomer and geometer

• A seller of laws

• An inspector

• Three bird-messengers

• Iris, daughter of Zeus, messenger of the gods

• A father-beater

• Cinesias, a famous poet

• An informer

• Prometheus, Titan and lover of humans

• Poseidon, god of the sea

• Heracles, demigod

• Triballus, a barbarian god

Setting

The first part of the play is set in the forest, just outside Hoopoe’s nest and the second is in heavens, in the newly-formed Cloud-cuckoo-land.

Summary of The Birds

Prologue

The opening scene of The Birds introduces us to a pair of typical Athenians with atypical names: Euelpides and Peisetaerus. Both names are invented by Aristophanes. Euelpides means “Good hope,” and Peisetaerus “Persuader of his comrade(s).” The latter name is a modern restoration. Most of the ancient manuscripts offer Peisthetaerus which, as Alan Sommerstein writes, is “an ungrammatical and meaningless form.” Older translations usually correct the name to either Peithetaerus or Pisthetaerus, but both variations “suggest obedient loyalty rather than persuasive leadership.” Different interpretations may justify these emendations as well (see “A Brief Analysis” below), but, on balance, Peisetaeurus seems the most acceptable.

At the beginning of the play, Peisetaerus and Euelpides are somewhere in a wild and desolate region and each of them has a bird in his hand. They are angry, and Euelpides soon reveals why: “That Philocrates, the bird-seller, played us a scurvy trick when he pretended these two guides could help us to find Tereus, the Hoopoe, who is a bird, without being born of one.” And why are they interested in finding Tereus? Turning to the spectators, Euelpides explains soon after:

“Born of an honorable tribe and family and living in the midst of our fellow-citizens, we have fled from our country as hard as ever we could go. It's not that we hate it; we recognize it to be great and rich, likewise that everyone has the right to ruin himself paying taxes; but the crickets only chirrup among the fig-trees for a month or two, whereas the Athenians spend their whole lives in chanting forth judgments from their law-courts. That is why we started off with a basket, a stew-pot and some myrtle boughs and have come to seek a quiet country in which to settle. We are going to Tereus, the Hoopoe, to learn from him, whether, in his aerial flights, he has noticed some town of this kind.”

It soon turns out that Euelpides was wrong in thinking that the bird-seller tricked them with the guides: his jay and Peisetaerus’ crow start exhibiting their true worth by directing the Athenians to a rock. Euelpides knocks on it and immediately attracts the attention of the Footbird, a majestic bird who turns out to be the slave of the Hoopoe. At the request of the two friends, the Footbird goes back behind the rock and his master, the Hoopoe, suddenly rushes forth from the thicket. He is not even nearly as imposing as the Footbird, but, nevertheless, has some answers to the questions of Euelpides. “Are you looking for a greater city than Athens?” he asks him after learning of the plights of the friends. “No, not a greater,” Euelpides answers, “but one more pleasant to live in.” In response, the Hoopoe starts suggesting him a number of places. A “city of delights” on the Red Sea is rejected because it is a sea-port, where no Greeks live. Lepreum in Elis is refused because of a certain tragedian named Melanthius. Finally, the Opuntian Locris is discarded because it’s, well, Opuntian. “But come,” asks suddenly Euelpides, “tell me: what is it like to live with the birds?” “Why, it's not a disagreeable life,” answers the Hoopoe, and goes all biblical in continuation, centuries before the New Testament: “In the first place, one has no purse… for food the gardens yield us white sesame, myrtle-berries, poppies and mint.”

Peisetaerus, silent up until this moment, suddenly bursts forth with a magnificent idea: “Ha!” he exclaims, “I am beginning to see a great plan, which will transfer the supreme power to the birds, if you will but take my advice.” The idea is not even that complicated: if the birds stopped flying undignifiedly in all directions and founded a city, the central position of their habitat between the humans and the gods should enable them to dominate both. “The air is between earth and heaven,” Peisetaerus explains further. “When we want to go to Delphi, we ask the Boeotians for leave of passage. In the same way, when men sacrifice to the gods, unless the latter pay you tribute, you exercise the right of every nation towards strangers and don't allow the smoke of the sacrifices to pass through your city and territory.” The Hoopoe is enchanted with the plan: he sincerely believes this might be the best idea ever conceived. So, he immediately summons his bird-friends.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The Chorus now appears. It consists of 24 different varieties of birds, assembled from all parts of the world. However, none of them seems particularly thrilled with Peisetaerus and Euelpides. On the contrary, in fact: seeing them for what they are – humans and ancestral enemies to their kind – the birds want to peck out the eyes of the Athenians before these two might trick them as most humans usually do. Peisetaerus and Euelpides arm themselves with kitchen utensils, and prepare to fight for their lives, but fortunately that turns out to be unnecessary, for the Hoopoe manages to calm the wrath of his bird-friends and induce them to listen to Peisetaerus’ impressive proposal.

Agon

Somehow, Peisetaeurus makes his proposal even more impressive. He claims that his goal with the establishment of a bird-city is none other but returning to the birds what was rightfully theirs. Using fanciful folk-etymology and citing dubious authorities such as Aesop, Peisetaeurus demonstrates to the birds that they were the masters of the universe before the Olympians. The Chorus is convinced: they enthusiastically express their support for Peisetaerus’ plan and give the two Athenians the right to transform into birds. So, Peisetaerus and Euelpides follow Hoopoe into his thicket where they are supposed to be given a magical root, leaving the Chorus alone on the stage to address the spectators and deliver the conventional parabasis.

First parabasis

However, the parabasis is anything but conventional: unlike all other parabases in Aristophanes’ comedies, this one is delivered by the Chorus as themselves, and not on behalf of the author. Consequently, the Chorus doesn’t talk about Athenian politics or the conditions of the contemporary stage, but about matters much more relevant to the plot of the play. Their new-found confidence is obvious from the very first verses of the parabasis, delivered by the leader of the Chorus, Procne, the nightingale-mate of Tereus in the myth:

“Weak mortals, chained to the earth, creatures of clay as frail as the foliage of the woods, you unfortunate race, whose life is but darkness, as unreal as a shadow, the illusion of a dream, hearken to us, who are immortal beings, ethereal, ever young and occupied with eternal thoughts, for we shall teach you about all celestial matters; you shall know thoroughly what is the nature of the birds, what the origin of the gods, of the rivers, of Erebus, and of Chaos.”

True to the promise, Procne proceeds by recounting the origin and early history of the universe in several beautiful verses that parody Hesiodic genealogies. Next, the Chorus reveals all the important services that birds have rendered to mortals for centuries, including marking the seasons, and helping humans in their prophecies. Then follows a lovely lyric, interspersed with bird-calls, praising the ability of birds to produce music, which morphs into a catalogue of all the advantages of possessing wings.

“If you recognize us as gods,” the birds sing, “we shall be your divining Muses, through us you will know the winds and the seasons, summer, winter, and the temperate months. We shall not withdraw ourselves to the highest clouds like Zeus, but shall be among you and shall give to you and to your children and the children of your children, health and wealth, long life, peace, youth, laughter, songs and feasts; in short, you will all be so well off, that you will be weary and cloyed with enjoyment.”

Episodes

At the conclusion of the parabasis, Peisetaerus and Euelpides emerge from the thicket, transformed into birds. Immediately, they set about organizing the new city, named Nephelococcygia, or, in literal translation, “Cloud-cuckoo-land.” Peisetaerus dispatches Euelpides on a complicated errand (to oversee the building of the city walls) and takes most matters into his own hands. A priest is summoned to perform a sacrifice in honor of the birds, but he is unable to conclude the seemingly endless list of birds to whom prayers are to be addressed, and Peisetaerus takes over the ritual himself.

Soon enough, several new problems emerge: having found out about the foundation of a new city, a bunch of Athenians come to Peisetaerus in search of new and better markets for their businesses. In rapid succession, he chases all of them: a young poet who offers himself as the official writer of Cloud-cuckoo-land, an oracle-monger who wants to sell the birds a few favorable prophecies, the famous mathematician and calendar-reformer Meton, who is interested in exercising his geometry in the planning of the town, an Athenian inspector with some personal interests, and a seller of decrees, who arrives with a complete set of laws originally written for a different town. The interruptions exhaust Peisetaerus who, fearing he might never finish his sacrifice in the open, retires into the thicket and leaves the Chorus to deliver the second parabasis of the play.

Second parabasis

In the second parabasis, the birds celebrate their newly-discovered power and decree several laws forbidding the catching, caging, stuffing and eating of their kind from then on. They extol their happy life and advise the judges of the Dionysian festival to award them the victory, lest they want to be defecated on by them.

Episodes

As soon as the Chorus ends the parabasis, Peisetaerus comes out of the thicket and announces that the sacrificial omens are favorable. Almost simultaneously with this proclamation, a messenger arrives and reports that the walls of Cloud-cuckoo-land have been completed, thanks to the collaboration of numerous birds and a few ingenious construction methods. There is not much time for rejoicing though: a second messenger soon reports that an Olympian god has found a way to evade the bird-guards and has sneaked into the city. The god, it turns out after a thorough search, was a goddess: Iris, the messenger of Zeus. She seems blissfully unaware of what’s happening in Cloud-cuckoo-land, and is amazed at the rude treatment she receives. Tearfully she leaves for Olympus planning to complain to Zeus about her treatment. Immediately after her departure, a third messenger arrives. This one informs Peisetaerus that Athens is in thrall to bird-mania, and almost everyone who doesn’t like Athenian politicians (and these don’t even seem to be a minority) likes to settle in Cloud-cuckoo-land. As a result, Peisetaerus is, once again, forced to deal with a few unwelcomed visitors: a father-beater, the poet Cinesias, and an informer. He chases all of them, with blows and threats, as it is obvious that all three of them see the empire of the birds as a utopia because its presumed laws suit to their personal needs and not because they want a better future for humanity.

Next, a secretive figure creeps in, carrying an umbrella to hide from Zeus and the heavens. Its identity is revealed a few moments later: it is Prometheus, the lover of humans and the enemy of Olympians. Peisetaerus greets him affectionally: finally, a welcome guest! And indeed, Prometheus has come to advise the founder of Cloud-cuckoo-land. Starring in a role mimicking the one he has in Aeschylus’ tragedy Prometheus Bound, the Titan reveals Peisetaerus not only that the Olympians are desperate for a peace treaty, but also that Zeus’ real power lies in his girlfriend, Basileia, the personification of Sovereignty. Consequently – Prometheus says – Peisetaerus should ask her hand in marriage and agree to nothing during the negotiations before he is promised it.

Prometheus leaves, and after a brief choral ode, an Olympian delegation arrives, made up of the sea-god Poseidon, the demigod Heracles, and Triballus, a barbarous Thracian deity. As advised by Prometheus, Peisetaerus demands that Basieleia be given to him in marriage, and that Zeus yield his scepter to the birds. He easily outsmarts Heracles who, in turn, bullies (or misinterprets) Triballus into submission. Upvoted, Poseidon has no choice but to agree.

Exodos (Exit Song)

The three gods depart, and Peisetaerus is presented with Zeus’ scepter by Sovereignty. The play ends with a wedding march and celebrations in honor of the new master of the universe.

A Brief Analysis

Ambitious and idealistic, The Birds is the most critically disputed of all Aristophanes’ plays. The absence of direct political allusions has led many to see it as “a play with a key,” and numerous critics throughout history have tried unearthing some real-life situations and figures behind the supposed façade of fiction and fantasy. For most of the 19th century, critics read The Birds as a sort of a reaction by Aristophanes to the Athenian campaign in Sicily and even “a sympathetic exploration of Athenian aspirations” in the new phase of the Peloponnesian War. Later on, many scholars tried interpreting Peisetaerus as a metaphor for Alcibiades, the loudest advocate for an aggressive foreign policy and the man who inspired the Athenians to attempt the Sicilian expedition.

None of these interpretations seem satisfying: trying to find political allusions in this play seems like a case of overinterpreting. Not only because Aristophanes is far more direct in his political allegories, but also because this comedy works well – if not better – as a utopian fantasy. And, indeed, modern critics tend to read The Birds as either “a non-topical flight of wish-fulfilling fantasy” or “a fanciful escape from an unpleasant reality.”

There are still some dissenting voices who, though not in favor of the “political allusion” interpretation, believe that The Birds is wholly political without making an attack on any specific political issues. These critics – wholly contrary to those of previous times – see the comedy as “a black and ironic dystopia” and Peisetaerus as “a self-seeking tyrant with delusions of grandeur.” They point out that, though it may look otherwise, the birds are actually the losers, and Peisetaerus the only real winner. By the end of the play, he has married a goddess and became the ruler of the universe with their help, and they have sacrificed their freedom for it. Though once free to fly everywhere they wanted, they are now confined in a city devised by someone who is not even one of them. Moreover, though Peisetaerus promises the birds to never be harmed again, in the scene with the ambassadors from Olympus, he is shown roasting birds “convicted of treason.”

However, if Aristophanes’ intention was to fool the spectators by portraying a utopian empire, while simultaneously laughing it off as a dystopia, he seems to have done a remarkably good job in the former and unsatisfactory in the latter. Consequently, in the words of Storey, “on balance, it seems preferable to regard this comedy as a marvelous piece of fantasy, without investing it with any more serious and sinister overtones.”

The Birds Sources

There are a few translations of Birds available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read an anonymous translation for the Athenian Society edited by Eugene O'Neill, Jr. here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Benjamin B. Rogers verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, Athens, Peace, Prometheus Bound

The Birds Video

The Birds Associations

Link/Cite The Birds Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "The Birds". GreekMythology.com Website, 03 Sep. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/The_Birds/the_birds.html. Accessed 24 April 2024.