Lysistrata

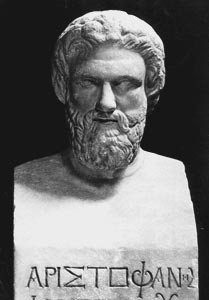

Lysistrata by Aristophanes

First performed in 411 BC (probably) at the Lenaea, Lysistrata is one of Aristophanes’ best-known comedies, primarily because of its modern adaptations as a feminist play. Written just two years after the disastrous failure of the Sicilian Expedition, the play follows an interesting attempt of the Athenian women (in collaboration with women from other Greek city-states) to bring an end to the Peloponnesian War. Led by a woman named Lysistrata, they occupy the Acropolis (with the object of denying Athens the financial resources to fight on) and launch a sex-strike as a way to enforce their husbands to negotiate peace. Coordinated with women from all the other cities across Greece, the plan works well for a while, despite temptations and tentative setbacks. Twelve old men (the first semichorus) arrive at the Acropolis with an intent to burn down its gates. However, they are easily dealt with by a corresponding semichorus of twelve old women. At the same time, Lysistrata successfully contends with the current magistrate (or proboulos) on whether war is a man’s or a woman’s affair. After some time, however, the rebellious women start feeling the pressure and the inconvenience of their own oath: most of them would rather the war went on than bear another day without sleeping with their husbands. Lysistrata rallies her forces, and convinces one of its most prominent members, Myrrhine, to seduce her husband Cinesias and leave him at the most critical moment. Soon after, a Spartan herald arrives at the Acropolis, and we realize that things are just as difficult in Sparta as they are in Athens. In a discussion with the Athenian magistrate, the two agree that it is smart for the peace talks to begin as soon as possible. As soon as they leave, the two semichoruses are reconciled, and the old men and women start kissing each other. During the peace talks, Lysistrata reminds the Spartans and the Athenians that they have a past history of cooperation and advises them to remain friends forevermore. She introduces the delegates to a gorgeous young woman named Reconciliation; unable to take their eyes off of her, the delegates fall under her spell and sign the peace declaration. Everybody retires to the Acropolis for further celebration. The play ends with Athenians and Spartans singing songs to each other in praise of past joint victories and future harmonious relations.

Date and Historical Background

Lysistrata was first performed in 411 BC, the year when another of Aristophanes’ plays, Women at the Thesmophoria, was also produced. The festival is not known for either, but, as Martin Revermann writes, “topical references in the play and our knowledge, from Thucydides, about the situation in Athens in early 411 lead most recent scholars to assume a performance at the Lenaea in early 411” (which would, in turn, mean a performance at the City Dionysia for Women at the Thesmophoria).

Revermann also points out that, as preserved in the manuscript tradition, the ending of the play is peculiar, especially in that it ends with the Spartan envoy calling for a hymn to a Spartan version of Athena. “The preserved script,” he writes, “may therefore originate from a version of the script that was revised for an audience in Sparta or, more probably, a Spartan colony (like Taras in south Italy). Related to this issue is the fact that our script of the play contains large portions of text spoken or sung in Spartan dialect (or, more precisely, Aristophanes’ representation of it), making Lysistrata, together with the archaic poet Alcman, the main literary source for this dialect otherwise only known from inscriptions.”

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Lysistrata, leader of the Athenian wives

• Calonike, a young Athenian wife

• Myrrhine, a young Athenian wife

• Lampito, a strong and beautiful Spartan wife

• An Athenian magistrate

• Cinesias, an Athenian citizen, husband of Myrrhine

• A Spartan herald

• A Spartan spokesman, leader of the Spartan envoys

• An Athenian spokesman, leader of the Athenian envoys

• Old men, semichorus of 12

• Old women, semichorus of 12

• Chorus, incorporating the two semichoruses in the exodos

Setting

Before the Acropolis of Athens.

Summary of Lysistrata

Prologue

Lysistrata begins with a discussion between the main protagonist of the play and Calonice, a young Athenian woman. “Oh, Calonicé, my heart is on fire,” says Lysistrata, “and I blush for our sex. Men say we are tricky and sly… and yet, when I summon the other women to meet for a matter of the greatest importance, they lie abed instead of coming.” Fortunately, after some time, the other women – such as, for example, Myrrhine and the beautiful and strong Spartan girl Lampito – do arrive and when all are assembled, Lysistrata unfolds her magnificent twofold scheme to end the Peloponnesian War.

“Oh! sister women,” she announces to the gathered folk, “if we would compel our husbands to make peace, we must refrain.” “Refrain from what?” they ask. “Tell us, tell us – we will do it, even if it means dying of it!” “We must refrain from the male altogether,” she replies. The implication is obvious: Lysistrata suggests that the other women should stop sleeping with their husbands until they come to their senses and start the much prolongated peace talks.

Suddenly, the mood among the other women changes. “No, I will not do it,” says resolutely Myrrhine. “let the War go on.” “Anything, anything but that!” shouts even more doggedly Calonice. “Bid me go through the fire, if you will; but to rob us of the sweetest thing in all the world, my dear, dear Lysistrata!” This brings Lysistrata to tears: “Oh, wanton, vicious sex!” she exclaims. “the poets have done well to make tragedies upon us; we are good for nothing then but love and lewdness!” The athletic Spartaness Lampito immediately proves her otherwise and jumps to her aid, claiming that as difficult as refraining from corporal pleasures might be, “Peace must come first.” Ultimately, the other women are swayed and they tearfully swear an oath of celibacy over a bowl of wine:

“I will have nothing to do whether with lover or husband, even if he comes to me with strength and passion. I will live at home in perfect chastity, beautifully dressed and wearing a saffron-colored gown to the end I may inspire my husband with the most ardent longings. Never will I give myself voluntarily, and if he has me by force, I will be cold as ice, and never stir a limb. I will not aid him in any way.”

Some of the women recognize that this scheme might not be enough to turn the men away from war. “So long as they have their trusty ships and their vast treasures,” notes Lampito, they will continue to fight. “That has already been taken care of,” replies surprisingly Lysistrata and reveals that the second part of her plan has already been put in motion. “This very day the Acropolis will be in our hands,” she says. “That is the task I assigned to the older women: while we are here in council, they are going, under pretense of offering sacrifice, to seize the citadel.” Soon after, a great commotion is heard offstage, signaling that the occupation of the Acropolis has gone according to the plan. With the revolution now well under way, Lysistrata and the other Athenian women head to the Acropolis, and Lampito and the other delegates from abroad head back to their cities out to incite similar rebellions.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The scene then shifts to the entrance of the Acropolis, where a group of old men, twelve in all, has gathered to burn down its gates unless the women inside open them. They intend to smoke the women out of the stronghold, but are met with some serious resistance. Armed with pots of water, the old women drench not only the old men’s torches, but their bodies as well.

Agon

At that very moment, accompanied by Scythian policemen, an Athenian magistrate arrives before the Acropolis and expresses his intent to take some silver from the state treasury to buy oars for the fleet. He has already heard about the insurrection of the Athenian women, but laughs off their capability to meddle in the affairs of men. “But you don't know all their cheekiness yet!” cries out the Leader of the first semichorus. “They abused and insulted us; then soused us with the water in their water-pots, and have set us wringing out our clothes.” The magistrate is still not especially concerned, and orders his officers to force open the gates.

“No need to force the gates,” says Lysistrata, authoritatively surfacing before the Acropolis. “I am coming out — here I am. And why bolts and bars? What we want here is not bolts and bars and locks, but common sense.” Common sense was not something the Scythian policemen were famous for, so before too long – and on the orders of the magistrate – they try to seize her. However, they are quickly overwhelmed by Lysistrata and the second semichorus, that of the old Athenian women.

The cowardice of his officers forces the dissatisfied magistrate to accept a discussion with Lysistrata. She wastes no time to point out to him how she and her sex have been totally neglected by men. “All the long time the war has lasted,” she says, “we have endured in modest silence all you men did; we never allowed ourselves to open our lips. We were far from satisfied, for we knew how things were going; often in our homes we would hear you discussing, upside down and inside out, some important turn of affairs. Then with sad hearts, but smiling lips, we would ask you: ‘Well, in today’s Assembly did they vote Peace?’ But, ‘Mind your own business!’ the husband would growl. ‘War is men’s business!” Not anymore, Lysistrata, goes on: men are going to listen to their wives’ opinions from now on, and they are going to reach a truce as soon as possible.

“May I die a thousand deaths before I obey one who wears a veil!” cries out the magistrate. “If that's all that troubles you,” replies Lysistrata in the most memorable line of the play, “here, take my veil, wrap it round your head, and hold your tongue. Then take this basket; put on a girdle, card wool, munch beans. The war shall be women's business from on.” Afterward, she lists two more reasons why – even though it is men who start wars and fight in them – it is women who suffer far more: not only are many of the fighters their children, but also the childless have no choice but “to languish far from their husbands, who are all with the army.” “Don't the men grow old too?” asks the magistrate. “That is not the same thing,” replies Lysistrata. “When the soldier returns from the wars, even though he has white hair, he very soon finds a young wife. But a woman has only one summer: if she does not make hay while the sun shines, no one will afterwards have anything to say to her, and she spends her days consulting oracles that never send her a husband.”

As convincing as they might sound, Lysistrata’s words fall on deaf ears. So, she and the second semichorus turn from words to deeds, soaking the magistrate with water and dressing him up like a corpse on a bier. He has no choice but to depart, shouting “insult” and promising to show himself to the other magistrates and rouse them to action. The victorious women can’t care less: they retire into the Acropolis, satisfied and full of revolutionary zeal.

Parabasis

The stage is thus left to the two semichoruses, and this seems like a great moment for them to unite and deliver the conventional parabasis. However, the interlude which follows, though formally similar to the second parabasis in The Birds, is, in substance, much more merely a continuation of the agon. Based on what follows, it must be supposed that a longer period of time passes during the altercation between the two semichoruses – a few days or even, more probably, months.

Episodes

Because when Lysistrata steps forth from the Acropolis the next time, she gives off vibes entirely different from the ones before. Soon enough, we hear why: she has started experiencing the characteristic difficulties of almost all revolutionary leaders – that is the cooling off of the initial enthusiasm and the growing number of defections. “I cannot stop the women any longer from lusting after the men,” she pessimistically explains to the semichorus of old women. “They are all for deserting. The first I caught was slipping out by the gate near the cave of Pan; another one was letting herself down by a rope and crane; a third was busy preparing her escape; while a fourth, perched on a bird's back, was just taking wing for Orsilochus' house, when I seized her by the hair. One and all, they are inventing excuses to be off home.” As she speaks, a few more women pass before her with even newer excuses to go home: one has some wool in her house that might be eaten by the worms lest she spreads it immediately, and another has left her flax unstripped. The most ingenious of the women-deserters feigns pregnancy by slipping the sacred helmet of Athena Pallas under her robe. The revolution – as most of them are – seems destined to fail.

But just then, Lysistrata notices an optimistic sign of weakness in the enemy: Cinesias, the husband of Myrrhine, arrives before the Acropolis, and it is obvious at first sight that – as difficult as the situation is for the women – it is unbearable for their significant others. Cinesias begs Lysistrata to call his wife. “Life has no more charms for me since she left my house,” he says. “I am sad, sad, when I go indoors; it all seems so empty; my food has lost its savor. And desire is eating out my heart!” Lysistrata does call Myrrhine, but instructs her to torture him as much as it is humanly conceivable. And even though Cinesias agrees to stop the war in order to sleep with Myrrhine right there on the spot, she merely tantalizes him with several delays until finally leaving him even more tortured than before. The old men of the first semichorus express their commiserations with the young men, but even they start to grow aware that the women might have the upper hand.

This is confirmed in the very next episode, in which a herald from Sparta comes across the Athenian magistrate from before just in front of the gates of the Acropolis. It is obvious from the Spartan’s physical appearance that Lampito has been just as successful in Sparta as Lysistrata in Athens. “Are you hiding a lance under your clothes” asks the Athenian magistrate, “or are you just happy to see me?” The two men agree that anything is more bearable than their current situation and leave off to fetch delegates and organize the peace talks.

As soon as they leave, the old men of the first semichorus concur defeat: “No wild beast is there, no flame of fire, more fierce and untamable than woman; the leopard is less savage and shameless.” “And yet you dare to make war upon me,” replies the leader of the female semichorus, “when you might have me for your most faithful friend and ally.” This is not merely a declaration, but an invitation: soon after, the old women start kissing the old men and the two semichoruses merge, anticipating the inevitable happy end.

Exodos (Exit Song)

The delegates return and the peace talks commence. Lysistrata reprimands both the Athenians and the Spartans for their past mistakes and introduces them to an immensely beautiful young woman named Reconciliation. In her presence, the delegates quickly overcome their differences and they call an end to the war. Afterward, they retire to the Acropolis for celebration. Men and women start dancing together and singing hymns in praise of Athena, without whose blessing the war would have probably still went on.

A Brief Analysis

Described as “one of Aristophanes’ most sophisticated comedies,” Lysistrata – as Alan Sommerstein says – has, essentially a triple plot. The main story is built around two separate schemes devised by Lysistrata: “the boycotting of sexual relations” and “the seizure by the Athenian women of the Acropolis, where the financial reserves of the state were kept.” These two are juxtaposed against the battle between the two semichoruses whose unification announces the reconciliation at the end. Aristophanes skillfully intertwines these three narrative arcs and uses all of them to explore two main themes: the battle of the sexes and peace. In the former, Lysistrata resembles the other play Aristophanes produced in 411 BC, Women at the Thesmophoria, and the penultimate of his surviving comedies, Assemblywomen; in the latter, it is the third and last of Aristophanes’ peace plays, coming after The Acharnians and Peace.

Unsurprisingly, Lysistrata is dominated by sexual imagery. Some of the names of the characters are probably meant as double entendres, and the principal image of the comedy is the erect male phallus, little used in other plays by Aristophanes but worn by almost all male characters in Lysistrata. According to Ian Storey and Arlene Allan, Lysistrata seems to be “the first comedy with a dominant female character (certainly a politically active female) and, while it does exploit the male stereotype about women (fond of sex, wine, and gossip), there are moments of real empathy, especially in Lysistrata’s description of how women are affected by war.”

Remarkably, it’s quite possible that she may be based on a real character. Alan Sommerstein writes: “At the time when Lysistrata was produced, the position of priestess of Athena – the highest appointment that any Athenian woman could hold – was occupied by a woman named Lysimache. Not only is the name strikingly similar to that of Lysistrata, both in form and in meaning, but in the play itself, the heroine expresses her confidence that ‘one day we will be known among the Greeks as Lysimachai’.” Lysistrata means “She who breaks up armies” and Lysimacha “She who breaks up battles.”

For most of history, Lysistrata was either censored or rarely performed because of “the play’s visible and all-pervasive obscenity.” However, as Revermann writes, beginning in the second half of the 20th century, it has probably become “the most widely known of all ancient comedies and the most regularly performed or adapted, often in a feminist and/or pacifist vein – the former despite the fact that gender relations revert to the status quo at the end, the latter despite the fact that Lysistrata explicitly sanctions war against barbarians (it is war of Greeks against each other that she is opposed to).”

Sources

There are a few translations of Lysistrata available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read an anonymous translation for the Athenian Society edited by Eugene O'Neill, Jr. here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Jack Lindsay’s verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, Women at the Thesmophoria, Assemblywomen, Peace

Lysistrata Video

Lysistrata Associations

Link/Cite Lysistrata Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Lysistrata". GreekMythology.com Website, 03 Sep. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/Lysistrata/lysistrata.html. Accessed 19 April 2024.