Wealth

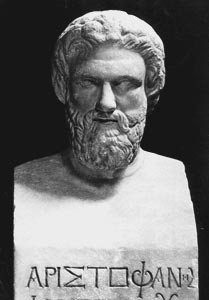

Wealth by Aristophanes

First produced two years before the death of the author, Wealth (or Plutus) is Aristophanes’ last surviving play. In essence, it is a twist on an observation probably as old as civilization itself – namely that “wealth is blind.” The meaning of the proverb is pretty straightforward: the evil are usually wealthy because the god of wealth, Plutus, is unable to distinguish good men from bad. If he could see – thinks Chremylus at the beginning of the play – then probably he would only reward the deserving. Together with his slave Cario, the two concoct a plan to help Plutus regain his sight. As Chremylus explains his plan to a neighbor named Blepsidemus, the two are confronted by an angry and ugly old woman. It turns out that this is no ordinary woman: it is Penia, the goddess of poverty. She explains to the two that they are about to make a big mistake, for lack of luxury and moral behavior are interconnected: the wealthy, she says, can’t be as good as the poor. She knows this, because it is she who makes men virtuous. Even so, Penia is quickly dismissed, and Plutus is carried off to the shrine of Asclepius, the god of medicine. When he exits the shrine, he is finally able to see, and starts redistributing the wealth among the people. Unsurprisingly, now that the rich are poor, they can’t help but feeling that the world is unfair and that they have been treated unjustly. At least this is the feeling of a former informer who comes to the house of Chremylus – where Plutus is now a permanent resident – to lament his destiny and threaten dire consequences unless things are returned to normal. After he is chased away, an ugly and wealthy old woman arrives to complain about the fact that her “toy boy” has left her: now that he is rich, he no longer needs her gifts and doesn’t even treat her nice. This is demonstrated to be more than true as the young man himself arrives and starts mocking his ex-mistress. Chremylus intervenes and forces him to continue the relationship. The next and penultimate guest is none other than Hermes who complains to Chremylus’ slave Cario that since nobody needs anything from the gods anymore, nobody sacrifices anything to them any longer. Hermes, however, would rather eat something than starve, so he offers himself as a servant to Chremylus in return for food. The final visitor is a starving priest of Zeus in desperate pursuit of a new savior. Chremylus gives him one: Plutus, the god of wealth, the new supreme deity of all Greeks.

Date and Historical Background

Ancient scholars attribute two plays entitled Wealth to Aristophanes. We know that one of these was produced in 408 and the other just two years before the death of the author, in 388 BC. Based on internal and external evidence, these two are not the same comedy and the one that has reached us is the latter one. It is Aristophanes’ last surviving play. He supposedly wrote two more after this one, but both of them were produced by his son Ararus. It is quite possible that he might have been heavily involved in the production of Wealth as well. It is not known at which festival Wealth was produced. We also don’t know which prize it won at the competition.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Chremylus, a poor but honest Athenian

• Cario, his slave

• Blepsidemus, his neighbor

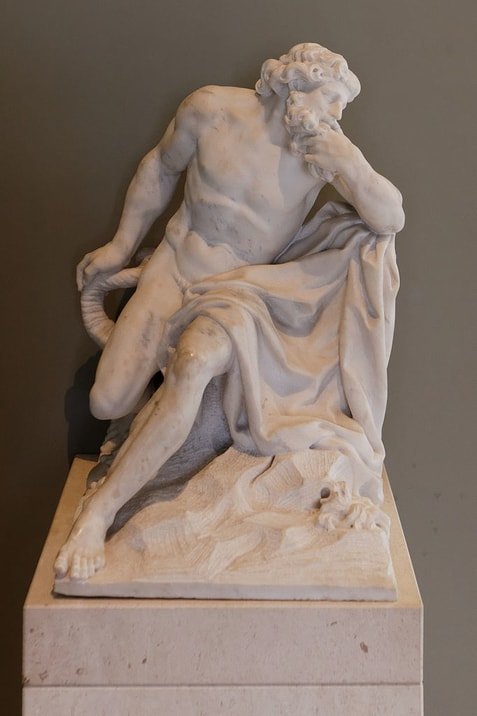

• Plutus, the god of wealth

• Penia, the goddess of poverty

• Chorus of farmers

• A Just Man

• An Informer

• An Old Woman

• A Young Man, the old woman’s former gigolo

• Hermes, the messenger of Zeus

• A priest of Zeus

Setting

On a street in Athens, just before Chremylus’ house.

Summary of Wealth

Prologue

A ragged old blind man is walking down an Athenian street; for some reason, two men are following him closely behind. “Is this not opposed to all good sense?” one of these two men suddenly asks, turning to the audience. “After all, it is for us, who see clearly, to guide those who don't; whereas my friend here clings to the trail of a blind fellow and compels me to do the same without answering my questions with ever a word.” The reason why this man – whose name is Cario – must obey the orders of his “friend” despite their supposed arbitrariness is quite simple: he is his slave. For precisely the same reason, his master Chremylus is not even interested into giving him an explanation.

However, after persistent questioning, Chremylus gives in. “All right, all right,” he says to Cario. “I will reveal the reason to you since you are both the most faithful and the most rascally of all my servants.” And then he starts explaining: “Well, you know that I honor the gods and do what is right, and yet I am poor and unfortunate… You also know that the worst are the ones who amass wealth: the sacrilegious, the demagogues, the informers, indeed every sort of rascal. Therefore, I came to consult the oracle of the god – not on my own account (for my unfortunate life is nearing its end) but for my only son. I wanted to ask Apollo if it was necessary for him to become a thorough knave and renounce his virtuous principles, since that seemed to me to be the only way to succeed in life. And the god ordered me in plain terms to follow the first man I should meet upon leaving the temple and to persuade him to accompany me home.”

Cario isn’t particularly pleased with the explanation, and – after unsuccessfully attempting to reinterpret the oracle – he insists on finding out who the blind man they are following actually is. After a few threats from Cario, the blind man sees no alternative to disclosing his identity, and he reluctantly reveals that he is Plutus, the god of wealth. “If you are a god, what’s with the blindness, then?” asks Chremylus. “Zeus inflicted it on me, because of his jealousy of mankind,” replies Plutus. “When I was young, I threatened him that I would only go to the just, the wise, the men of ordered life; to prevent my distinguishing these, he struck me with blindness!” When Plutus promises to visit only the good and shun the wicked once he is able to distinguish between the two, Chremylus is inspired to a great idea: to help the god regain his sight and thus rectify all the ills of human life.

Promising to make him even mightier than Zeus, Chremylus discloses Plutus his plan and invites him to his humble abode. Though skeptical at first, Plutus is eventually persuaded – what’s he got to lose? – and the two enter Chremylus’ house. Cario is sent to fetch his good friends, the farmers, and in a few seconds, he comes back with them.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Cario explains to the farmers – who comprise the Chorus, and play a pretty unimportant role in the comedy – that his master is planning to drag them out the “stupid, sapless lives they are leading and ensure them one full of all delights.” At first, they don’t believe him, but they start rejoicing after Chremylus’ slave discloses the identity of his master’s new friend. “What joy, what happiness!” they sing. “If what you tell me is true, I long to dance with delight.”

Episode

The dancing is interrupted by Chremylus, who comes out of his house to greet the farmers. They barely exchange a few words when a neighbor of Chremylus by the name of Blepsidemus appears. “What has happened then?” he asks his old friend. “Whence, how has Chremylus suddenly grown rich? I don't believe a word of it. Nevertheless, nothing but his sudden fortune was being talked about in the barbershops! Have you really grown rich as they say?” “I shall be soon,” replies Chremylus. This gets Blepsidemus’ attention and he starts asking Chremylus all kinds of questions. His attitude is bordering on hostile: he believes that Chremylus might have stolen something or is else planning to. Eventually, Chremylus tells him everything and makes it clear that, if his plan works, he will not be the only one to profit. Blepsidemus is persuaded, and he offers his help. “Let’s go and seek physician,” he suggests. “Seek physicians at Athens? Nay! there's no art where there's no fee,” replies Chremylus. “I have thought the matter well over, and the best thing is to make Plutus lie in the Temple of Asclepius.” Blepsidemus agrees. The two are just about to leave when an angry, dirty and absolutely terrifying woman comes running in.

Agon

“Unwise, perverse, unholy men! What are you daring to do, you pitiful, wretched mortals? Whither are you flying? Stop! I command it!” she shouts. “My arm shall destroy you, you infamous beings! Such an attempt is not to be borne; neither man nor god has ever dared the like. You shall die!” Blepsidemus and Chremylus are shocked and, based on the “wild tragic look” in the woman’s eyes, confuse her with a Fury. It turns out that she is actually something far worse: Penia, the goddess of poverty, “the most fearful monster that ever drew breath.” She begs to differ: “By driving me out,” she says, “you are doing humanity a great harm.” How so, wonders Chremylus, and Penia starts explaining, promising to get out of their way if she doesn’t succeed in demonstrating that she is the sole cause of all of humanity’s blessings.

“Let Plutus recover his sight and divide his favors out equally to all,” says she soon after, “and nobody will work or create anything any longer; all toil would be done away with. Who would wish to hammer iron, build ships, sew, turn, cut up leather, bake bricks, bleach linen, tan hides, or break up the soil of the earth with the plough and garner the gifts of Demeter, if he could live in idleness and free from all this work?” And that is only the first of Penia’s three arguments. The second one is directly connected to the first: in a world where everybody is rich, there will be no one to do the lowly jobs. And what’s the point of being rich if you don’t have a slave to do them all for you? However, it is only after Penia’s third argument that Chremylus falters a bit and can’t help but start agreeing with her.

“What you don't know is this,” says the goddess of Poverty. “Men with me are worth more, both in mind and body, than with Plutus. With him they are gouty, big-bellied, heavy of limb and scandalously stout; with me they are thin, wasp-waisted, and terrible to the foe... Modesty dwells with me and insolence with Plutus… Only the poor are good and just.” “That is absolutely true, although your tongue is very vile,” replies Chremylus. “But, tell me this, then: why does all mankind flee from you?” “Because I make them better,” explains Penia. “Children do the very same; they flee from the wise counsels of their fathers. So difficult is it to see one’s true interest.”

Just when it seems they might change their minds, Blepsidemus and Chremylus choose to ignore the logic of Penia’s arguments. “You won’t persuade me,” says Chremylus, “even if you’ve managed to convince me.” So, Penia leaves with cries and threats, while Chremylus summons Cario, with whom he conducts Plutus to the temple of Asclepius where he is supposed to be healed of his blindness.

Choral Interludes

Just like in Assemblywomen, there is no parabasis in Wealth as well: merely a brief interlude of dancing by the Chorus. But it must be assumed that a considerable amount of time has lapsed during this interlude, because by the time it ends, Cario is already able to report to his friends, the farmers, about the successful cure that has been performed on Plutus in what has been described as “one of the most detailed descriptions of an Asclepian healing.” Another interlude follows, but this one is interrupted by the return of the joyful Plutus. “I want to change everything,” he cries out. “In the future I mean to prove to mankind that, if I gave to the wicked, it was against my will.”

Naturally, Aristophanes gives Plutus the chance to prove his moral purity, and us, the spectators, the chance to see how this might work in practice. After a third interlude – during which we must suppose that a few days or even months might have passed – Cario returns to the stage to announce “what a delightful thing is wealth” and “how pleasant it is to live well, especially when it costs nothing.” Most of the people seem to share Cario’s feelings – but there are some who don’t. We meet members of each of these groups in the following few scenes, each of which illustrates the various social effects of the economic revolution enacted by Plutus.

Episodes

We are first introduced to “a man who was once wretched, but now is happy.” A just man, he has come before the house of Chremylus to merely thank Plutus (who now lives with his benefactor) for all the blessings he has been showered with and dedicate his old cloak and shoes to the god.

Next, an Informer enters, followed by a witness. “Alas! alas! I am a lost man,” he cries. “Ah! thrice, four, five, twelve times, or rather ten thousand times unhappy fate! Why, why must fortune deal me such rough blows?” We learn from the subsequent discussion between him, Cario and the Just Man that he is mad at Plutus for taking away his wealth and giving it to others. However, it is obvious that he is a scoundrel and Cario and the Just Man strip him off his cloak and shoes and chase him away. On departing, he threatens them: “I'm off, for you are the strongest, I own. But if I find someone to join me, let him be as weak as he will, I will summon this god, who thinks himself so strong, before the court this very day, and denounce him as manifestly guilty of overturning the democracy by his will alone and without the consent of the Senate or the Assembly.”

Next an Old Woman arrives, dressed as a young girl and trying to walk in an alluring manner. Her problem? Now that her “toy boy” is rich, he has no reason to consort with her. Chremylus mocks her, but, for some reason, changes the tune once he gets to know the young man himself who enters just after the Old Woman, wearing a garland on his head and carrying a torch in his hand. “Since you liked the wine,” Chremylus says, “you should now consume the lees.”

Soon after the three enter the house, Hermes arrives and starts knocking at the door of Chremylus’ house. Cario opens and is somewhat happy to discover the severity of Hermes’ distress: now that all humans are wealthy, nobody seems bothered about sacrificing to the gods who – just like in The Birds – are short of food. In return for some, he offers himself as a servant to Chremylus. He immediately gets a job from Cario: “Go and wash the entrails of the victims at the well, so that you may show yourself serviceable at once.”

The final guest is a priest of Zeus. His problem is similar to that of Hermes: since nobody sacrifices anything to the old gods, he has nothing to eat. “Hence,” he explains to Chremylus, “I think I am going to say goodbye to Zeus the Savior, and stop here myself.” “Be at ease,” replies Chremylus, “for all will go well, if it so please the god. Zeus the Savior is here; he came of his own accord.”

Exodos (Exit Song)

The comedy ends somewhat abruptly: Plutus solemnly comes out of the house, followed by the Old Woman from before. Chremylus promises to her that the young man will spend the night with her, and the Chorus starts singing a song and decides to withdraw.

A Brief Analysis

According to Eugene O’Neill Jr., Wealth is “the least amusing” of Aristophanes’ extant comedies. “Its chief interest for the modern reader,” he writes, “lies in the fact that it is the nearest thing to a representative of the Middle Comedy that has come down to us. The later centuries of the ancient world and the schoolmasters of the Byzantine Empire, however, were inordinately fond of it, the former because of what they regarded as its refinement, the latter because it only infrequently offended their moral tastes.” And, indeed, Wealth was by far Aristophanes’ most studied play in the Byzantine and early modern period, surviving in almost 150 manuscripts, some 20 more than its nearest rival, The Clouds. Moreover, as Matthew Dillon writes in The Encyclopedia of Greek Comedy, Wealth was the first play by Aristophanes to be (partially) translated into Latin, and the only one of the great comedian’s works to influence Shakespeare: directly or indirectly, it must have served as a source for the Bard’s Timon of Athens.

O’Neill Jr. remarks that “if we make Wealth the first, rather than the last, comedy of Aristophanes that we read, we [may] find it a sufficiently amusing play, but if we come to it fresh from Peace or Women at the Thesmophoria, it is a singularly disappointing performance.” Even though merely a speculation, it feels justified: there’s little of the richness of Old Comedy in Wealth, and the play does look as if it is a precursor rather than a successor of Aristophanes’ great comedies. Just like Assemblywomen – Aristophanes’ other surviving comedy of the 4th century – it “depicts an economic revolution that does away with the great inequalities of wealth and poverty, not this time by the abolition of private property but by the redistribution of wealth, supposedly to the deserving but in practice to everyone, creating a fantasy golden age of limitless prosperity in which citizens need do nothing but eat, drink, and be merry, no doubt a reaction to the realities of Athenian life in the aftermath of defeat in the Peloponnesian War” (Matthew Dillon).

And probably because reality was so bad in Athens at the time the play was first produced, the main question of the comedy – why do the gods allow virtuous men to be poor and villains to flourish? – remains pretty much unanswered. However, “critics have not missed the fact that Penia speaks second in the agon – the usual winning position – and that Chremylus does not so much win the debate as ride roughshod over Poverty. To many, this suggests that the entire second half of the comedy should be read as intentionally ironic.” And, indeed, the behavior of the young man toward his ex-mistress allows such an interpretation: maybe Penia was right from the start, and maybe, the only thing that Plutus’ regained eyesight brought about was role-reversal, and nothing more.

Sources

There are a few translations of Wealth available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read an anonymous translation for the Athenian Society edited by Eugene O'Neill, Jr. here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Benjamin B. Rogers verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, Assemblywomen, Women at the Thesmophoria, Lysistrata

Wealth Video

Wealth Associations

Link/Cite Wealth Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Wealth". GreekMythology.com Website, 03 Sep. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/Wealth/wealth.html. Accessed 19 April 2024.