The Acharnians

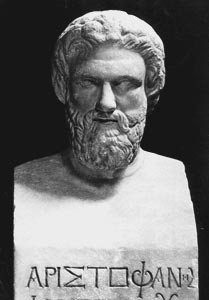

The Acharnians by Aristophanes

Produced at the Lenaea in 425 BC, The Acharnians is the third play composed by Aristophanes, his earliest extant work, and the earliest Ancient Greek comedy that has survived entirely intact to this day. In its prologue, Dicaeopolis (whose name means “honest citizen”) tries to convince the Athenian assembly to end the ongoing Peloponnesian war – the major conflict between Athens and Sparta – but he fails to do so. So, he sends a demigod named Amphitheus to Sparta to negotiate a private peace for him and his family. This is met with violent disapproval from the Chorus, made up of the inhabitants of Acharnae, the largest center of population in Attica outside of Athens and the strongest supporter of war against Sparta. Dicaeopolis confronts them by disguising himself as Telephus, a beggar from the eponymous Euripides’ play (now lost), and parodying the war as a destructive event from which only profiteers can benefit. Some of the Acharnians are convinced by Dicaeopolis’ arguments, but some aren’t, so a fight breaks out. It is interrupted by the Athenian general Lamachus who is then questioned by Dicaeopolis regarding his reasons to favor war over peace. It is obvious from the discussion that Dicaeopolis was right all the time, so all of the Acharnians are now converted. They praise him, and in the second part of the play we see why. Because of the private peace he has negotiated with Sparta, Dicaeopolis is able to entertain visitors from enemy territories, including a Megarian who wants to trade his daughters for food and a Boeotian who, in return for a few birds and eels, gets a member of a prized breed to take with him to his home country: an Athenian sycophant. At this moment, two heralds arrive – the first one calls Lamachus to war, and the second one Dicaeopolis to a drinking party. The negative symmetry is retained in the closing scene as well: after some time, Lamachus arrives home wounded with soldiers at each arm holding him up, and Dicaeopolis is carried off drunk in the arms of dancing girls to a private celebration.

Date and Historical Background

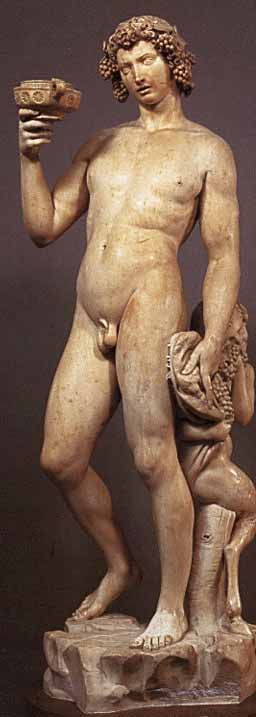

The Acharnians was first produced in 425 BC at the Lenaea– an annual Athenian festival celebrating Dionysus – where it won first prize, Cratinus being second with Storm-Tossed, and Eupolis third with New Moons. The play belongs to the period of Old Comedy and is a highly political play: it advocates peace and calls for an end of the highly destructive Peloponnesian War, then in its sixth year. The War will unfortunately last for two more decades, prompting Aristophanes to write a few more plays that essentially bear the same message as this one.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Dicaeopolis, an “honest man”

• Amphitheus, a demigod-messenger to Sparta

• Ambassador from the Persian court

• Pseudartabas, a supposed Persian dignitary

• Theorus, ambassador to Thrace

• Euripides, the great tragedian

• Lamachus, an Athenian general

• A Megarian with his two daughters

• A Boeotian

• Two Athenian informers, an anonymous one and Nicarchus

• Two heralds

Setting

The first part of the play is set on the Pnyx at Athens, a hill where the Athenians gathered to host their assemblies. The second part is set on a street connecting the house of Dicaeopolis with those of Euripides and Lamachus.

Summary of The Acharnians

Prologue

The Acharnians begins with Dicaeopolis (whose name can be translated as “honest citizen”) soliloquizing in an empty Pnyx, the meeting-place of the Athenian Assembly (the ecclesia), just inside the city wall to the west of the Acropolis and the Areopagus. It is the sixth year of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta.Dicaeopolis is frustrated with the fact that few people seem to share his opinion that continuing the war further is pointless. He recalls the peaceful life of past years, and laments the indifference of the absent Athenian magistrates to the cares and worries of the common man who certainly prefers the normalcy of peace to the death and destruction of war. “Therefore,” Dicaeopolis says, “I have come to the assembly fully prepared to bawl, interrupt and abuse the speakers, if they talk of anything but peace.”

Soon enough, the magistrates start arriving. Their interest in their own wellbeing (and disinterest in the wellbeing of the city) is symbolically portrayed in their first act: most of them start pushing and fighting for the front seats. That is merely the beginning: all of the speakers that address the assembly afterward talk of matters dear to themselves and don’t even mention peace.

The first speaker is an ambassador who has returned from the Persian court after many years. Throughout his complaints (for they are phrased as such), we learn that he is paid by the city a hefty sum (two drachmae per diem) to enjoy life at the Persian court, where he has “suffered horribly… stretched on fine chariots” and “forced to drink delicious wine out of golden or crystal flagons.” The ambassador introduces a man named Pseudartabas, the Eye of the Great Persian King, accompanied by some eunuchs. Supposedly he speaks beautiful things in Persian (with the ambassador translating), but Dicaeopolis recognizes the identity of the eunuchs (some Athenians in disguise) and sees through the ploy. It doesn’t matter: Dicaeopolis is silenced, and Pseudartabas is invited to the Prytaneum where he is promised entertainment at public expense.

Next comes Theorus, a recently returned Thracian ambassador. He has stayed in Thrace at the public’s expense long past his due, and he now blames the icy conditions of the region for his long stay there. He introduces a pair of Thracian soldiers (from the Odomantian tribe) as supposedly elite mercenaries resolved to fight for Athens and “put all Boeotia to fire and sword” for a wage of two drachmae (Boeotia was an ally of Sparta). The Odomantians, however, are not above stealing Dicaeopolis’ garlic, and are clearly not what they have been introduced to be.

Dicaeopolis is disgusted by all of this and causes the abrupt end of the Assembly meeting by announcing an omen: a single drop of rain. Here Aristophanes satirizes the disinterest of the public officials in general peace and prosperity, by demonstrating how the sitting of the Assembly (such an important event) was often declared at an end at the least unfavorable omen.

Fed up with everything, as soon as the meeting dissolves, Dicaeopolis hires a messenger – a demigod named Amphitheus (meaning “divine on both sides”) – to bring samples of “treaties” from Sparta. The word for “treaty” (spondai) also means “wine libation” (or “drink-offering”) in Ancient Greek and it’s interesting to see how Aristophanes manages to build an entire episode (and even a central metaphor of the play) around this pun. Because soon enough, vintage wines are brought from Sparta as a private peace offering. Dicaeopolis quickly chooses the thirty‐year “treaty,” thus reminding Athenians of the one ratified, but not observed, between their city and Sparta in 446 BC. He chooses to apply this peace offering for himself and his family only. Then he goes off to celebrate the peace at a private Rural Dionysia.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Just then, an angry mob of war veterans and charcoal-burners coming from Acharnae (the largest deme in Athens) attacks Dicaeopolis’ house. Thirsting for revenge against the Spartans for their recently pillaged land, the Acharnians seek to lynch Dicaeopolis for making peace with their enemies. “You impudent rascal, traitor to your country,” they shout, “you alone amongst us all have concluded a truce with our enemies, and you dare to look us in the face! We will stone you!” Dicaeopolis is adamant that he has done nothing wrong: “No, no,” he replies, “the Spartans are not the cause of all our troubles, and I who address you claim to be able to prove that they have much to complain of in us.” This, however, angers the Acharnians even more, and Dicaeopolis starts asking for mercy. The Acharnians instantly deny it to him.

Episodes

Shouting injustice, Dicaeopolis resorts to one last effort to save himself: he takes hostage the “dearest friend” of the Acharnians – a basket of charcoal. The scene is funny but it is also truthful to the conditions at the time: charcoal was one of the primary sources of revenue for Acharnae, and, moreover, the citizens of the deme were known for their zealous local patriotism. “Great Gods!” exclaim the frightened Acharnians. “But this basket is our fellow-citizen! Stop, stop, in heaven's name!” Dicaeopolis agrees to spare the life of the basket but asks the Acharnians to throw their stones and listen to him. They agree. “Well, speak now if you will,” says their leader. “Tell us, tell us you have a weakness for the Lacedaemonians. I consent to anything; never will I forsake this dear little basket.” Dicaeopolis is so sure that he is on the side of justice that he proposes to speak “in favor of the Lacedaemonians with his head on a chopping block.”

At this moment in the comedy, Dicaeopolis says something rather strange: “I have not forgotten how Cleon treated me because of my comedy last year.” Perhaps he was played by Aristophanes himself in the play’s original production and the dramatist breaks the fourth wall here, or perhaps Dicaeopolis is the comedian’s alter-ego. Either way, what the line refers to is something that was fresh in the memory of contemporary Athenians: in 427 BC, Aristophanes produced the now-lost comedy The Babylonians. Soon after, Cleon – a demagogue and a warmongering general – denounced the author to the Senate for mocking Athens before foreign guests, many of whom were present at the performance.

Interesting in itself, the line is an introduction to an even more interesting episode. “The time has come for me to manifest my courage,” exclaims Dicaeopolis soon after, “so I will go and seek Euripides.” Curiously enough, Euripides seems to live just a few houses down the street of Dicaeopolis. Aristophanes thus ridicules the improbable plot twists in Euripides’ tragedies, which, in his opinion, are manipulative and are used by the tragedian to only attract the attention of the less refined among the audience. The critique continues in the quick discussion between Dicaeopolis/Aristophanes and Euripides, in which the former asks the latter the rags of the beggar Telephus (hero of a Euripidean play produced in 438 BC), because otherwise, the Chorus might not understand the gravity of his speech.

“I must today have the look of a beggar,” says, tongue-in-cheek Dicaeopolis, quoting a line from Euripides’ play: “to be what I am, but not appear to be. The audience,” he goes on, “will thus know well who I am, but the Chorus will be fools enough not to, and I shall dupe 'em with my subtle phrases.” He is only half right. Dressed as Telephus and with his head literally on a chopping block, Dicaeopolis traces the origins of the Peloponnesian War to a ridiculous reason: drunken Athenian and Megarian youngsters kidnapping each others’ prostitutes. This may be a parody of the origins of the Trojan War or even a parody of some of Herodotus’ accounts in his Histories. Either way, Dicaeopolis points the finger of blame to one man and one man only: Pericles. It was him – he says – who proclaimed (in a fiery reaction to these kidnappings) that “the Megarians be banished both from our land and from our markets and from the sea and from the continent.” Indeed, historians agree that Pericles’ Megarian Decree – which levied economic sanctions upon Megara – sparked off the Peloponnesian war; the Decree may have even been a deliberate provocation.

In his speech, Dicaeopolis claims that he is not a traitor, but Athenian politicians like Pericles are: they are the ones that started the war and the ones who might profit most from its continuation. This convinces half of the Chorus, but the rest of the Acharnians are still not persuaded. A fight breaks out and it ends with the appearance of real-life Athenian general Lamachus – another important character of the play who extraordinarily turns out to be a next-door neighbor of Dicaeopolis.

As soon as Lamachus restores order, Dicaeopolis starts questioning him regarding his motives to take part in the Peloponnesian War and the process by which he was elected to be a general. From the discussion, it becomes obvious that Lamachus is precisely the kind of man that Dicaeopolis despises: a corrupted opportunist who defends the just cause of the war because he can only earn money if Athens’ military budget is full. Moreover, Dicaeopolis can’t understand why everything else in Athens is decided by drawing lots, and the appointment of generals by election. He criticizes this because it creates a vicious cycle, with profiteers and warmongers choosing the future generals between them. Both Lamachus and Dicaeopolis go home, with the former one announcing eternal war and the latter one proclaiming his markets open to all Peloponnesians, Megarians and Boeotians – but not to Lamachus.

Parabasis

This time, all of the Acharnians are convinced that Dicaeopolis speaks the truth and approve him for having concluded peace with Athens’ supposed enemies. In the parabasis, they step forward and talk to the audience about Aristophanes’ important comedies and “Cleon’s tricks and plotting” and, especially, about the hostility between the older generations such as themselves and the younger such as the one represented by Lamachus. They had fought valiantly in the Persian Wars and saw war as something unifying and heroic; the new ones seem nothing more but sophists and lawyers who are not only oblivious of Athens’ glorious past, but indifferent toward its future. Unlike them who had fought for the city and the state – the younger generations seem to fight for themselves only.

Episodes

At this point, Dicaeopolis comes back to the stage and Aristophanes allows us to see the consequences of his peace agreement, as different individuals approach him with trade offers.

First, a starving Megarian offers him his famished daughters – disguised as “little pigs” – in return for some food. An Athenian sycophant (an informer) appears and denounces the Megarian and his “pigs” as public enemies and tries to confiscate the “animals.” Dicaeopolis drives him off and the trade is concluded to the pleasure of both sides. “Here is a man truly happy,” comment the Acharnians. “See how everything succeeds to his wish. Peacefully seated in his market, he will earn his living.”

Next, a Boeotian arrives and tries to sell Dicaeopolis some birds and eels. Unfortunately, Dicaeopolis has no “Athenian produce of renown” to offer him in return. Neither anchovies nor pottery interests the Boeotian. “Ah! I have the very thing,” exclaims with joy Dicaeopolis. “Take away an Informer, packed up carefully as crockery-ware.” Informants, explains Dicaeopolis, might be rare in Boeotia, but Athens has them a plenty. The deal is made and the Boeotian takes back home a man named Nicarchus – an informer who suddenly appears to denounce him.

Exodos (Exit Song)

After a few more self‐contained scenes, two heralds arrive on the street. One of them calls Dicaeopolis to a dinner party – and the other one calls Lamachus to battle. The juxtaposition between peace and war is made even more memorable as the two main characters of the play simultaneously gear up, hastily assembling their respective accessories. After a choral song, the two return: Lamachus wounded and held by two soldiers, and Dicaeopolis drunk and supported by two dancing girls. As Lamachus retreats in pain, the Acharnians join Dicaeopolis in a celebratory song. “Old man, I come at your bidding!” they sing. “You triumph! you triumph, brave champion!”

A Brief Analysis

The Acharnians is one of Aristophanes’ three “peace plays” (the other two being Peace and Lysistrata). At the time it was first performed, Athens’ war against Sparta and Boeotia had been in progress for nearly six years, bringing death and destruction on both sides. 427 BC was a particularly bad year for Athens. Because of this, there were many Athenians demanding the war to be continued until final victory (like the Chorus) and many others insisting that the war should be ended and normalcy restored (like Dicaeopolis). It’s obvious, from the play’s ending, that normalcy for Aristophanes means free trade, merry celebrations and joyous sexuality – three things that had been tainted by the war.

In Dicaeopolis’ opinion, these are the values of the common citizen, and since the war doesn’t represent them, it is the effort of profiteers and politicians, the only ones who gain something out of it. Aristophanes doesn’t hold back the punches: he directly attacks contemporary political figures, such as Pericles (for bringing war to Athens), the general Lamachus (for warmongering) and his favorite target Cleon (for misappropriation of public money). Just a year before The Acharnians was performed, Cleon had accused Aristophanes of slandering against the Athenian polis in his play Babylonians (now lost). Here (and elsewhere) the comedian gets his revenge.

And that is another thing that The Acharnians explores: the role of comedy in public life. Aristophanes was a very good connoisseur of tragedy, and had a lifelong fascination with Euripides. Even though he was mainly antipathic to the tragedian, he was very well acquainted with his work and was obviously fascinated with its effects on society (which he deemed detrimental). As we can see from The Acharnians, ever since the beginning of his career, Aristophanes was resolved to achieve something similar with his comedies. It’s questionable how much he succeeded: the Peloponnesian War lasted two more decades after The Acharnians. Despite winning the first prize at the Lenaea, its message was lost in the midst of the loud laughter. Apparently and unfortunately – there seem to have been more Lamachuses than Dicaeopolises among the Ancient Athenians.

The Acharnians Sources

There are a few translations of The Acharnians available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read a modernized version of an anonymous 1912 translation for the Athenian Society here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Charles Billson’s verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, Athens, Sparta, Peace, Lysistrata

The Acharnians Video

The Acharnians Associations

Link/Cite The Acharnians Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "The Acharnians". GreekMythology.com Website, 03 Sep. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/The_Acharnians/the_acharnians.html. Accessed 25 April 2024.