Assemblywomen

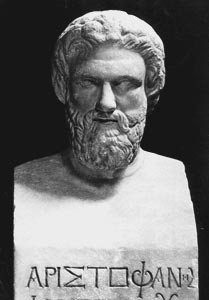

Assemblywomen by Aristophanes

First performed between 393 and 389 BC, Assemblywomen (or Ecclesiazusae) is, chronologically, the penultimate of the eleven surviving plays by Aristophanes, and, arguably, one of his least celebrated – at least as a literary work. However, the similarities between some aspects of the play and the utopian ideas of Plato in his Republic have made Assemblywomen the subject of numerous comparative analyses and philosophical or historical speculations. The plot of Aristophanes’ shortest comedy is fairly simple and concerns a scenario where the Athenian women assume power in the city and immediately introduce sexual equality and ban private property. The scheme is the brainchild of a woman named Praxagora and is presented at the beginning of the play. Following her directives, the Athenian women mask themselves as men (by appropriating their husbands’ clothes and putting on false beards) and go to the Athenian assembly with the intention of proposing and voting for a law that should hand over all power to the women. Coming over from the assembly, a man named Chremes happens upon Praxagora’s husband Blepyrus (curiously dressed in his wife’s robes and slippers) and tells him that the assembly – thanks largely to the unprecedented turnout of pale-faced shoe-makers – has voted to put the women in charge of the city. Soon after, Praxagora returns home and Blepyrus accuses her of sneaking away in the night with her lover and using his clothes to hide herself from the eyes of the neighbors. Praxagora successfully defends herself from the charge, and acts all surprised when Blepyrus tells her of the assembly’s strange decision. That doesn’t stop her from describing how the new government will operate and listing several progressive measures that cannot but remind one of Plato’s utopia: gender equality, common parenting, community of possessions. The idea is immediately put to the test, as a selfish man refuses to contribute to the common fund – while intending to enjoy the benefits. In another episode, a young man is forced to sleep with an ugly old woman before earning the right to enjoy the love of his eager young girlfriend. Finally, a drunken maid celebrating the new laws calls Blepyrus to an inaugural dinner – and finds him already on the way there with two girls under his arms.

Date and Historical Background

It is fairly clear from ancient sources that Aristophanes did a great deal of writing after The Frogs (405 BC), but none of the plays written in the following 13 years have come down to us. Note that 13 is a tentative number, because 392 BC is only the most probable date for the first production of The Assemblywomen – certainly one of Aristophanes’ latest works and practically the only one of his extant plays for which no certain date can be established. However, based on both internal and external evidence, we know that it must precede Wealth (388 BC) and that it is highly unlikely that it was produced before 393 BC. It is also not known whether it was originally performed at the Lenaea or the City Dionysia.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Praxagora, an Athenian wife

• First Woman, a neighbor of Praxagora

• Second Woman, another neighbor of Praxagora

• Blepyrus, husband of Praxagora

• Neighbor of Blepyrus

• Chremes

• Selfish Man

• Herald, a woman appointed by Praxagora

• Three old women

• Girl

• Epigenes, a young man

• Maid of Praxagora

Setting

An Athenian street.

Summary of Assemblywomen

Prologue

Assemblywomen begins in a much similar manner as Lysistrata, a play with which it shares several similarities. In a street near the public square in Athens, Praxagora anxiously awaits before her house the arrival of her fellow conspirators. One by one they all arrive. “Have you the beards that we had all to get ourselves for the Assembly?” Praxagora asks them. After getting an affirmative answer, she is pleased to note, under the weak light, that she doesn’t even need to ask the follow-up questions: “I see that you have got all the rest too, Spartan shoes, staffs and men's cloaks, as it was arranged… So come,” she cries out, “let us finish what has yet to be done, while the stars are still shining; the Assembly, at which we mean to be present, will open at dawn.” Praxagora’s plan soon becomes a bit clearer: she has gathered all the Athenian women at this hour – and made them steal their husbands’ clothes – so that they can infiltrate the Assembly and seize the helm of state from the hands of the incompetent men. And they plan to do this as legally as possible: by proposing and voting for a law granting power to the women.

Of course, they will first have to convince the other male members of the assembly to put this new law for voting. They discuss between hem who should be their representative, and Praxagora proves by far the best speaker – not the least because she has lived on the Pnyx (the hill where the assemblies were hosted) and has listened to past orators. She even rehearses her speech for the other women to hear – of course, assuming the role of a man standing in front of other men at the assembly. “I assert that the direction of affairs must be handed over to the women, for they are the ones who have charge and look after our households,” she says, to the loud approval of her fellow conspirators. And then she goes on to list all the ways in which women are better than men. Aristophanes uses the opportunity to insert a few backhanded compliments:

“They are worth more than you are, as I shall prove. First of all they wash all their wool in warm water, according to the ancient practice; you will never see them changing their method. Ah! if Athens only acted thus, if it did not take delight in ceaseless innovations, would not its happiness be assured? Then the women sit down to cook, just as they always did; they carry things on their head just as they always did; they keep the Thesmophoria, just as they always did; they knead their cakes just as they always did; they make their husbands angry just as they always did; they receive their lovers in their houses just as they always did; they buy dainties just as they always did; they love unmixed wine just as they always did; they delight in being loved just as they always did. Let us therefore hand Athens over to them without endless discussions, without bothering ourselves about what they will do; let us simply hand them over the power, remembering that they are mothers and will therefore spare the blood of our soldiers; besides, who will know better than a mother how to forward provisions to the front? Woman is adept at getting money for herself and will not easily let herself be deceived; she understands deceit too well herself. I omit a thousand other advantages. Take my advice and you will live in perfect happiness.”

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The women agree that with such a speech, their success is all but guaranteed. They agree to not betray their sex and are led by Praxagora off to the Assembly. Assuming the role of the Chorus, the women start singing: “Let us drive away these men of the city who used to stay at home and chatter round the table in the days when little money was paid to talk at the assembly; now, there are crowds at the Pnyx – but for all the wrong reasons…”

Episodes

A few hours after the women’s departure, a somewhat strange-looking figure emerges from Praxagora’s house: it is her husband, Blepyrus, only dressed in his wife’s saffron robe and wearing her Persian sandals. He is distressed, because he could find neither his wife, nor his clothes in his house. And since he desperately needed to relieve himself, he quickly donned the only thing he could find: his wife’s nightgown.

Soon enough, a neighbor of his appears on the street. “Man, where is your cloak?” he asks, worried that Blepyrus might have become a crossdresser overnight. “I cannot tell you,” replies Blepyrus. “I hunted for it vainly on the bed. And I couldn’t ask my wife because I couldn’t find her as well! She has run away, and I greatly fear that she might be off with her lover.” “But, by Poseidon,” responds the neighbor in shock. “It's the same with myself! My wife has disappeared with my cloak, and what is still worse, with my shoes as well; I cannot find them anywhere. I would like to go to the Assembly, but I've got to find my cloak first; I have only one.”

However, it soon becomes clear to Blepyrus and his neighbor that going to the assembly might not be necessary anymore. Not merely because its meeting has finished as they were trying to find their clothes, but also because men are no more in power in Athens. This news is related to the two by a man named Chremes, just returning from the assembly. “There was a crowd,” explains Chremes, “such as has never been seen at the Pnyx, and the folk looked pale and wan, like so many shoemakers, so white were they in hue.” When one of these shoemakers – an incredibly handsome young man – held an eloquent speech explaining that the direction of matters should be entrusted to women, the crowd began applauding with all their might and enthusiasm. “And what was decided?” asks Blepyrus. “To confide the direction of affairs to them,” replies Chremes. “And why not? It's the one and only innovation that has not yet been tried at Athens.”

Blepyrus is more delighted than concerned. His only fear: that the women might enact a law by which they would not give their husbands dinner unless they sleep with them first. But he is willing to take one for the team. “It's an old saying that our absurdest and maddest decrees,” he says, “always somehow turn out for our good.” With these words, Blepyrus, his neighbor and Chremes part, all of them going to their houses.

A few moments later, Praxagora and the other women (who form the Chorus) return triumphantly from the assembly. Most of them – fortunately – have enough time to take off their false beards and change their clothes before Blepyrus appears in the doorway. Praxagora, however, is still wearing his cloak.

Agon

“Eh, Praxagora, where are you coming from?” Blepyrus asks his wife, convinced that he has caught her committing infidelity. But Praxagora is not an easy nut to crack: “A companion, a friend who was in labor, had sent to fetch me,” she explains, offering as evidence her looks. Would she have ever gone to a lover without perfuming her hair, and, moreover, dressed in man’s apparel? Blepyrus is convinced, but nevertheless scolds her for her behavior: because of her hastiness he couldn’t go to the assembly and earn some money for making an appearance. “And don't you know the decrees that have been voted?” he asks Praxagora. At first, she feigns ignorance, but upon “finding out,” can’t help but rejoicing enthusiastically at the news.

At this point, Chremes appears once again eager to find out why should women be better at ruling Athens than men. Praxagora, turning to the audience, starts explaining, listing all the ways in which the society would profit from the change. And she lists them in a way that leaves everyone around her convinced that she is the de facto new ruler of Athens. Her proposal for the new, better society anticipates Plato’s proposal in The Republic and, in many ways, Karl Marx’s communism.

“I shall begin by making land, money, everything that is private property – common to all,” Praxagora says. “Then we shall live on this common wealth, which we shall take care to administer with wise thrift… The poor will no longer be obliged to work; each will have all that he needs, bread, salt fish, cakes, tunics, wine, chaplets and chick-pease… Women shall belong to all men in common, and each shall beget children by any man that wishes to have her… The ugliest and the most flat-nosed will be side by side with the most charming, and to win the latter's favors, a man will first have to get into the former.”

Even though they have some doubts, Blepyrus and Chremes are eventually converted. Chremes heads home to gather his belongings and add them to the common fund, and Praxagora – to the marketplace, where she is supposed to supervise the redistribution of property. Captivated by the prospect of being pointed out by other Athenians as the husband of Athens’ leader, Blepyrus follows his wife in jubilant mood.

Episodes

Now, Praxagora’s project is put to the test of reality. Chremes has indeed gathered his property and is now at the marketplace, intending to devote it all to the common store. A nameless citizen – let’s call him the Selfish Man – thinks this an utmost folly. “I shall not be fool enough to strip myself of the fruits of my toil and thrift,” he says, “if it is not for a very good reason.” His plan: to wait and see how the others act first. Chremes, nevertheless, remains convinced that he is doing the right thing. A female herald arrives and announces a luxurious feast provided by the state. “Well, if I’m commanded by the state,” says the Selfish Man, “then it would be unlawful of me to not go, right?” Chremes can’t believe his ears: “But you haven’t deposited your belongings,” he says. “You cannot go.” Even so, the Selfish Man doesn’t want to back down, claiming that he’ll deposit his things later. “If the women have any wits, they will first insist on your depositing your goods,” remarks Chremes. The Selfish Man barely even takes into consideration this possibility, adamant that he deserves the same as others, despite lack of contribution.

The next episode puts another of the decrees to the test: the one proclaiming sexual equality. According to the new Athenian laws, to win the favors of the young and beautiful women, men must first satisfy the appetites of the old and the unattractive. A young man by the name of Epigenes finds himself strongly attracted to a beautiful young girl who undoubtedly shares the enthusiasm for him. It doesn’t matter, since an older woman asks from him to obey the law. His resistance and arguments don’t help him one bit and he is dragged by the old woman to her house. Just then, the girl rescues him, but his joy is short-lived, because, almost immediately, an older and uglier woman than the first one claims right upon his services. Unfortunately, just as this second old woman is taking Epigenes home with her, a voice from behind demands to know where she is going. The young man thanks the gods for this interruption, only to find that his savior is yet another old woman, hideous beyond belief. As Epigenes curses his destiny, the two women drag him away against his will.

Exodos (Exit Song)

At this moment, a servant-maid of Praxagora appears, coming from the banquet, and looking for her mistress’ husband. “Oh! master! what joy! what blessedness is yours!” she exclaims upon noticing him. “None can compare his happiness to yours; you have reached its utmost height, you who, alone out of thirty thousand citizens have not yet dined. Where are you off to.” “Well,” answers Blepyrus, “just there: I am going to dine.” As he leaves with a few girls under his arms, the Chorus joyfully announces that they will soon be eating “lopadotemachoselachogaleokranioleipsanodrimhypotrimmatosilphioparaomelitokatakechymenokichlepikossyphophattoperisteralektryonoptekephalliokigklopeleiolagoiosiraiobaphetraganopterygon” – which is some sort of a stew, and more interestingly, the longest word ever constructed in Ancient Greek. Its meaning: “oysters-saltfish-skate-sharks’-heads-left-over-vinegar-dressing-laserpitium-leek-with-honey-sauce-thrush-blackbird-pigeon-dove-roast-cock's-brains-wagtail-cushat-hare-stewed-in-new-wine-gristle-of-veal-pullet's-wings.”

A Brief Analysis

At only 1180 verses, Assemblywomen is a short comedy. One of only two surviving plays by Aristophanes performed in the 4th century, it shows all the signs of the decline of Old Comedy: the agon is fairly one-sided, there is no parabasis, and the role of the chorus is minimized. Just like Lysistrata and Women at the Thesmophoria, Assemblywomen deals with reversals of gender roles and (though ironically) with the contribution of women to society. Arguably, though – at least in retrospect – it deals with them in a much more mature manner. Assemblywomen, writes Robert Tordoff in The Encyclopedia of Greek Comedy, “is the first developed exploration of communism in Western literature. Similarities between certain aspects of Praxagora’s communism and the system practiced by the Guardians in Book 5 of Plato’s Republic have occasioned a long‐running debate over the sources of Aristophanes and Plato’s ideas and whether one writer influenced the other. Others have detected analogies between Aristophanes’ communist polis and Sparta.”

The feeling is shared by Eugene O’Neill Jr. who writes something similar. “The Utopia established by Praxagora bears so remarkable a resemblance to the ideal state described in Plato’s Republic that the precise nature of the obvious connection between the comedy and the dialogue has been the subject of much discussion. The chronological difficulty arising from the fact that The Republic cannot have been published until about twenty years after Assemblywomen leaves us a choice of two explanations, since no one wishes to assume that the philosopher's theories were derived from the dramatist’s caricatures. It may be that community of property had already been suggested as a social and economic panacea, but it seems more reasonable to suppose that the ideas presented in The Republic were known for some time before their final publication.”

Alan Sommerstein lists all the similarities between Assemblywomen and Plato’s Republic and concludes that, amazingly, “of all the significant features in Praxagora's exposition of her new society, the only ones not represented in Plato are the detailed regulations governing sex – which are too comic to be capable of adaptation for a seriously designed utopia; the assurance that women will continue to do textile work as hitherto; and some remarks on crime and its punishment.” Does that mean that utopias are impossible because one’s paradise is another person’s hell? Aristophanes doesn’t deal with this question – but, two and a half millennia after him – we certainly can.

Assemblywomen Sources

There are a few translations of Assemblywomen available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read an anonymous translation for the Athenian Society edited by Eugene O'Neill, Jr. here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Benjamin B. Rogers verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, Lysistrata, Women at the Thesmophoria, Wealth

Assemblywomen Video

Assemblywomen Associations

Link/Cite Assemblywomen Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Assemblywomen ". GreekMythology.com Website, 17 Jan. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/Assemblywomen_/assemblywomen_.html. Accessed 15 April 2024.