The Wasps

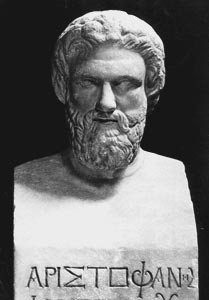

The Wasps by Aristophanes

First produced at the Lenaea festival of 422 BC, The Wasps is, probably, the sixth comedy written by Aristophanes and the fourth in chronological order of the eleven surviving ones. Just like a few other of his plays, it explores a conflict at the level of a single household to comment on the broader Athenian social or political situation. It begins with the slaves Xanthias and Sosias explaining to the audience that their old master, Philocleon (meaning “The one who loves Cleon”), suffers from a strange kind of affliction: he is a trialophile, that is, he is addicted to jury service. To keep him at home, his son Bdelycleon (“The one who loathes Cleon”) has imprisoned him in the house, under a large net. The old master tries various tricks to get out and head toward the law court, but is repeatedly unsuccessful. A group of fellow jurors – twenty or so elderly impoverished Athenians, costumed as wasps – arrives and inspires Philocleon to an audacious escape attempt. This rouses the household and brings the situation to a head, resulting first in a direct physical confrontation between the two camps, and then in a battle of wits (agon). During the debate, Philocleon defends his addiction by claiming that jurors are respected and feared in Athens, while Bdelycleon attacks this position by demonstrating to what extent they are used by the politicians for their own self-interest. At the end, a compromise is reached: Philocleon is allowed to remain a juror – but only at home, where he is supposed to judge domestic affairs. Soon after, the first case is brought before him: one of the household dogs is accused by another for stealing some cheese and not sharing it. Used to convicting people, Philocleon tries to reach a verdict of guilty, but is duped by his son into putting his vote in the urn for acquittal. Shocked by this outcome, he gives himself over to Bdelycleon who promises to introduce him to a life of luxury now that the jury days are behind him. This doesn’t go according to plan: first Bdelycleon has troubles attiring his father in finer clothing (Philocleon is also addicted to his juryman’s cloak) and then is unable to train him in the rules of the fashionable society. As a result, Philocleon wreaks havoc on a dinner party, insulting the guests, stealing a music-girl, and assaulting a bystander on the way home. Because of this, though the play ends in a celebratory mood, there is a note of ambiguity: has, by curing his father from his addiction, Bdelycleon created a greater social nuisance than ever?

Date and Historical Background

The ancient introduction (hypothesis) suggests that Aristophanes finished second with The Wasps at the Lenaea of 422 BC. Philonides was victorious with Preview, and Leucon finished third with Ambassadors. However, the production information may be corrupt, since Philonides is known to have been a producer for Aristophanes, having produced Frogs a year before The Wasps. Moreover, almost every other mention of Preview attributes the comedy to Aristophanes. Two things are possible: either the production notes of two different festivals were mixed up by a scriber, or Aristophanes tricked the judges at the Lenaea into winning two prizes in 422 BC, by submitting one of his comedies under Philonides’ name. The ruse might have been discovered only after and this can explain why Preview was originally listed under Philonides’ name, and afterward ascribed to Aristophanes. The rules of the festivals strictly forbade for one author to compete with more than one play, but similar ploys have been used by other writers in other countries and ages (for example – as he would reveal in his posthumously published memoirs – French writer Romain Gary won the Goncourt Prize twice in the 20th century by lying about his identity and having his cousin’s son posing as the author on the second occasion).

If Preview was also written by Aristophanes, then there’s a funny intertextual reference in the prologue of The Wasps. At one place, Xanthias says to the audience that the author will not be making fun of Euripides in this play – but we know for a fact that Euripides was a character in Preview, so the implication might be that he will be ridiculing the great tragedian in his other play. The audience would have, of course, heard the joke differently – as a cheap shot taken at a rival-dramatist, unaware that Philonides’ play was actually Aristophanes’. But, then again, Aristophanes didn’t care that much for the audience’s opinion, and he makes this clear in The Wasps as well, blaming his viewers for their lack of critical taste in not awarding his previous play (The Clouds – which Aristophanes considered his masterpiece) the first prize at the preceding Lenaea festival.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Philocleon, an old juror

• Bdelycleon, his son

• Xanthias, a slave in the house of Bdelycleon

• Sosias, another slave in the house of Bdelycleon

• Chorus of twenty-four old Athenian jurors dressed as wasps

• Two household dogs

• Myrtia, a baking woman

• Two citizens assaulted by Philocleon

Setting

In the street before the house of Philocleon and Bdelycleon.

Summary of The Wasps

Prologue

The Wasps opens with a late-night dialogue between two slaves, Xanthias and Sosias, in front of a house surrounded by a huge net. The latter wakes the former and the two interpret each other’s dreams before becoming aware of the presence of the audience. “Come,” says Xanthias turning in their direction, “we must explain the matter to the spectators.” Then he sets out the dramatic situation via an extended exposition.

We learn that the old master of the house, Philocleon (that is “Lover of Cleon”), is addicted to jury duty to such an extent that he has completely forsaken personal hygiene and regular sleep schedule. He can’t help himself from judging and convicting people: he has never acquitted anyone in his whole career. He constantly wears his old juryman’s cloak and even hoards pebbles for fear that he might run short of them when a sentence should be passed. “Such is his madness,” says Xanthias, “that all advice is useless: he only judges the more each day.”

After failing to convert him through gentleness, religion, and medicine, Philocleon’s son, Bdelycleon (that is, “Hater of Cleon”), stretched nets all around the house and set Xanthias and Sosias to keep watch and ward his father. He himself is half-awake most of the time as well, for Philocleon is difficult to keep at home even with a net. Speaking of which, as soon as we are introduced to the situation, Bdelycleon appears from the roof and announces an escape attempt: Philocleon is trying to leave the house through the chimney. Fortunately, the three arrive at the final moment to push him back inside. “What are you doing, you wretches?” shouts Philocleon. “Let me go out; it is imperative that I go and judge, or Dracontides will be acquitted!”

Philocleon tries hard to convince his son and his slaves to let him out, and even threatens to gnaw through the net with his teeth. However, neither his attempt to summon an invented ancient oracle nor his claim that he must sell the household’s donkey at the market amount to something. But the victory is short-lived: just as Bdelycleon succeeds in containing his father, a group of old jurors costumed as wasps and guided by lantern-carrying boys arrives before the house.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

Nearing the door of Philocleon’s house, the leader of the jurors announces casually the incoming trial of the real-life Athenian general and aristocrat Laches, who has supposedly embezzled a pot of money. He also claims that Cleon, “the protector of jurors,” has advised them “to come early and with a three--days’ stock of fiery rage so as to chastise Laches for his crimes.” They are on their way to the court, but have arrived here to fetch Philocleon, the most dedicated juror of them all. The leader is surprised not to find him before the door: is it possible that he is not ready? Perhaps, he guesses, the recent acquittal of an accused man so distressed Philocleon that he is now in bed with fever – or even tumor! Worried, the jurors keep calling Philocleon – but their calls and songs seem to be all in vain.

Episode

Having heard their voices, Philocleon suddenly appears at an upper window of the house and starts explaining his troubles to his friends in a song. After becoming acquainted with the situation, the jurors encourage Philocleon to try to escape once again and offer their help. It’s already dawn, after all, and they risk being late for their early arrival on the trial of Laches. “There’s no other way,” says Philocleon, “but gnawing through the net. Oh! goddess who watches over the nets, forgive me for making a hole in this one.”

Soon after, Bdelycleon, Xanthias and Sosias are awaken by Philocleon’s escape attempt: he has pierced a hole through the net and is now trying to escape by climbing down a rope. They run to stop him, but at the same time the jurors try to stop them. The result is a physical confrontation from which – despite the numerous stings of the jurors – Bdelycleon and his slaves emerge victorious: Philocleon is prevented from escaping, and the Chorus retreats, but not before blaming Bdelycleon of tyrannous behavior. “Everything is now tyranny with us, no matter what is concerned, whether it be large or small,” laments Bdelycleon in response. “Even if you are buying gurnards and don't want anchovies, the huckster next door, who is selling the latter, at once might exclaim, ‘That is a man whose kitchen savors of tyranny!’”

Philocleon sees nothing wrong in this: in democratic society, everyone has the right to judge everyone else – and that is a great thing! Bdelycleon begs to differ and believes he can convince Philocleon that he deceives himself. “I deceive myself, when I am judging?... I a slave, I, who lord it over all?” – replies in shock Philocleon. “Yes,” his son says. “You do not see that you are the laughing-stock of these men, whom you are ready to worship. You are their slave and do not know it.” This exchange sets the scene for a debate – the agon, or the battle of wits.

Agon

In the debate, Philocleon tries to prove that “there exists no king whose might is greater than his.” He is respected and feared, because he can condemn anyone to prison or death. Moreover, he earns quite a lot of money from this endeavor and is privileged to be above the law: since he is the one who judges, there’s no one to judge him. In fact, the jurors’ decisions are never subjected to reviews. “We are the only ones whom Cleon, the great bawler, does not badger,” claims Philocleon. “On the contrary, he protects and caresses us.” At the time The Wasps was first performed, Cleon was de facto the most powerful man in Athens. Unfortunately for him, he was also a thorn in Aristophanes’ side – he had accused him before the Council of ridiculing Athens before foreign guests in one of his plays.

Aristophanes’ revenge is scattered across several of his comedies. Here, it comes first in Bdelycleon’s reply to his father’s claims. The son argues that the jurors are merely playthings in the hands of Athens’ powerful elite, and that this is the reason why they don’t bother with them. Cleon cares for the jurors not because they serve the city’s welfare, but because they work for his interests: he uses them to stifle the opposition and earn a lot of money. Moreover, he deliberately keeps them poor so that he can easily control them. And he does just that: Bdelycleon compares the jurors to the hired laborers who gather olives – they too follow the one who pays them. “That is why I always kept you shut in,” he says to his father. “I wanted you to be fed by me and no longer at the beck of these blustering braggarts. Even now I am ready to let you have all you want, provided you no longer let yourself be suckled by the pay clerk.”

The jurors are convinced by Bdelycleon’s arguments, and Philocleon is stunned into silence and critical self-reflection. However, he is not willing to give up his addiction just yet. “Ask me anything, anything,” he says to his son, “except one: not to judge anymore! I will die before consenting to this.”

Episode

Fortunately, Bdelycleon has devised a plan for this kind of scenario as well. He immediately establishes a comfortable domestic lawcourt, at which he holds a trial that is meant to mimic the one against Laches. His place is taken by a dog named Labes which is accused by another dog representing Cleon – the dog of Cydathenaea – for stealing and devouring a Sicilian cheese all by himself, without accomplices. The penalty demanded by the prosecution is a collar of fig-tree wood for Labes. A few household objects – “a plate, a pestle, a cheese knife, a brazier, a stew-pot and other half-burnt utensils” – are called as witnesses. Of course, they utter not a single word, and the same holds true for Labes. “I think he has got what happened once to Thucydides in court,” remarks Bdelycleon. “His jaws suddenly set fast.” So, he undertakes his defense and asks the jury to consider the fact that Labes was always a good dog, protecting the house and the flocks from wolves and other impostors. “He is the best of all our dogs,” remarks Bdelycleon, and invites his children, a group of puppies, to beg and whine on his behalf. For a moment, Philocleon’s heart is softened, but he refuses to acquit Labes after all. However, his son fools him and he puts his vote into the urn for acquittal. “It’s all over for me!” grumbles Philocleon after finding out the outcome of the trial. “Do not vex yourself, father,” replies Bdelycleon. “I will feed you well, will take you everywhere to eat and drink with me; you shall go to every feast; henceforth your life shall be nothing but pleasure.”

First parabasis

As soon as the son ushers his father inside the house to prepare him for some revels, the jurors (still masked as wasps) turn to the spectators and address them in a conventional parabasis. They reprimand them for not appreciating Aristophanes enough and for awarding him only the third prize for his previous play which they consider a masterpiece (The Clouds). They further praise the comedian for standing up to Cleon when nobody else would, and juxtapose their admiration for the older generations of heroes with their displeasure of the contemporary politicians who treat the city funds as their own.

Episode

The parabasis is interrupted by Philocleon’s loud refusal to give up his old juror’s cloak and shoes. Bdelycleon wants him to wear more sophisticated clothes for the dinner party the two are supposed to go, but can only alter his wardrobe after forcing the new clothes upon him. After teaching him how to behave in the company of the powerful men he is about to meet, the two depart for the dinner party.

Second parabasis

This allows for a brief second parabasis, in which the Chorus lauds a few honorable Athenian citizens, and comments upon the conflict between Cleon and Aristophanes. They claim that Aristophanes has tricked the politician into thinking the two are reconciled – something that will never happen regardless of the threats and persecutions.

Episodes

Suddenly, Xanthias appears on the stage and announces that Philocleon is “the worst of all plagues.” Asked by the jurors about the meaning of these words, he proceeds to explain his drunken antics at the dinner party and on his way home. As soon as he departs, Philocleon arrives, with a beautiful flute-girl under his arm. Bdelycleon appears in a while and, after scolding his father for kidnapping the girl, he tries to forcefully free her; instead, he is knocked down by Philocleon. Shortly after, two men appear before the house: they claim to have been attacked by Philocleon on the street and threaten to take him into court. Bdelycleon protects him by dragging him indoors, leaving the Chorus, once again, alone on the stage. In a brief song, they commend Bdelycleon for his devotion to his father and bemoan the fact that men find few things more difficult than changing their habits – no matter how bad they might be.

Exodos (Exit Song)

Philocleon – disguised as Polyphemus from Euripides’ satyr-play Cyclops – comes out of the house, followed by his son and Xanthias. He is still cheerful and ecstatic. He begins to dance in a manner parodying that of Euripides, and, upon noticing them down the street, he challenges the sons of Carcinus to a contest. Everybody starts dancing and rejoicing.

A Brief Analysis

As Ian Storey points out, The Wasps exemplifies the conventions of Old Comedy at their best, and is unified in action, time and place. Its plot spans a single, complete day in the life of an individual Athenian household. Its setting never shifts: from beginning to end, it takes place in the street before the house of the two main protagonists. There is also a pretty tight dramatic focus: the whole play concerns Bdelycleon’s attempts to cure his old father Philocleon of his addiction for jury service.

As funny as it is, The Wasps treats two very serious matters: the demagoguery of Cleon and the failings of the Athenian jury-system. Just a few years before the first production of the play, Cleon had brought an unsuccessful prosecution against the fellow-general Laches for his defeat during the first Sicilian expedition against Sparta. Somehow, Laches escaped civil punishment, but Cleon subsequently raised the pay of the jurors, probably in an attempt to have even more influence on them in the future. Aristophanes criticizes not only this action, but also the jury-system in entirety. Notoriously conservative, the comedian was hardly a democrat, and in The Wasps he attempts to demonstrate why. In his opinion, ordinary people such as Philocleon and the jurors of the Chorus can be easily manipulated by the worst of the worst – turning democracy into oligarchy.

Politics aside, the tight structure, the exquisite portrayal of addiction and a father-son relationship, as well as the lively and unforgettable Chorus of jurors make The Wasps one of the greatest comedies in the history of literature.

The Wasps Sources

There are a few translations of The Wasps available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read a modernized version of an anonymous translation for the Athenian Society here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Benjamin B. Rogers verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, The Knights, The Acharnians, Peace

The Wasps Video

The Wasps Associations

Link/Cite The Wasps Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "The Wasps". GreekMythology.com Website, 03 Sep. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/The_Wasps/the_wasps.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.