Women at the Thesmophoria

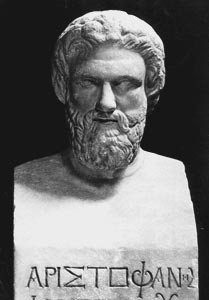

Women at the Thesmophoria by Aristophanes

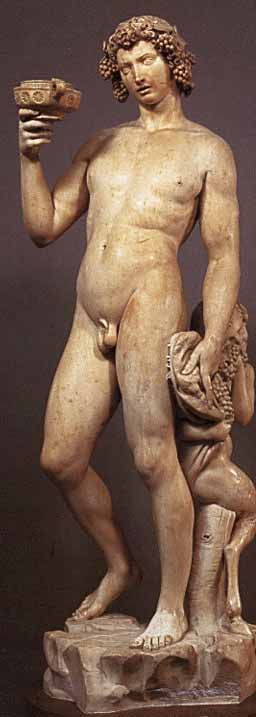

First performed in 411 BC (probably) at the City Dionysia, Women at the Thesmophoria (also known under its Latin title Thesmophoriazusae) is considered Aristophanes’ wittiest parody of life in 5th-century Athens. Thesmophoria was a three-day festival held in honor of the goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone, restricted only to adult women. In Aristophanes’ play – incensed by their unfavorable portrayal in Euripides’ tragedies – the Athenian women use this festival as an opportunity to devise a revenge plan against the tragedian. Euripides, however, finds out about this and, with the help of his relative Mnesilochus, asks Agathon – a real-life tragic poet with overtly effeminate traits – to infiltrate the festival and plead his case. After Agathon refuses, the plan is slightly modified: it’s Mnesilochus who will now try to gain access to the Thesmophoria by posing as a woman. Consequently, he is singed, shaved, and dressed in women’s clothing. The third and final day of the festival begins and Mnesilochus is able to take part in the discussion concerning Euripides. To the women who blame Euripides for revealing too much of their daily lives to the world, he replies that they should be thankful to the tragedian because he has opted not to tell the whole, odious truth about them. The ensuing argument is interrupted by Cleisthenes, a notorious homosexual and the only man allowed to attend women’s gatherings. He reveals to the women that their meeting might have been infiltrated by a male relative of Euripides. Mnesilochus is consequently unmasked, proven to be male, and bounded to a plank by a Scythian officer. In an attempt to get him out of there, Euripides enters and leaves the scene several times, each time in a different disguise and each time parodying his own plays with the help of his cousin. Because this bears no result, the tragedian finally decides to appear as himself and makes a deal with the women: if they release his relative, he says, he will refrain from abusing Athenian women in the future. The women agree and allow Euripides to free Mnesilochus which he succeeds after disguising himself once more, this time as an old lady.

Date and Historical Background

Women at the Thesmophoria (or, better yet, Women Celebrating the Thesmophoria) was first performed in 411 BC, probably at the City Dionysia. The play has reached us without an “introduction” (hypothesis), but scholars have successfully deduced the date and the place by comparing an internal cue with the available external evidence.

Namely, in line 1060, Euripides (disguised as Echo) reveals that Euripides’ Andromeda was produced “last year… in this very place.” According to an ancient scholar commenting Aristophanes’ Frogs, Andromeda was first performed eight years before Frogs (i.e., 412 BC), placing Women at the Thesmophoria the following year. This date is confirmed by other ancient commentators that, at various places, set the death of Lamachus (415 BC) four years before the performance of Women at the Thesmophoria, and the death of Euripides six years later (Euripides died in 406 BC).

In 411 BC, Aristophanes also produced Lysistrata, and it’s difficult to know which play was performed at which festival. However, since Euripides/Echo in the play claims that Women at the Thesmophoria was performed at the very same place as Andromeda – and since tragedies were more commonly performed at the City Dionysia – it’s more likely that Women at the Thesmophoria was first shown at the City Dionysia. Moreover, Andrew Hartig – in The Encyclopedia of Greek Comedy – remarks that Women at the Thesmophoria “appears to reflect better the tumultuous political circumstances around late February and early March, when Athens reluctantly voted to temporarily change its constitution to a moderate oligarchy and accept Persia as its ally in the war against Sparta.”

Characters and Setting

Characters

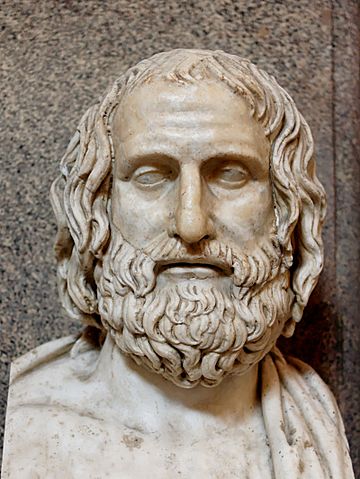

• Euripides, one of the three greatest Athenian tragedians

• Mnesilochus, an elderly relative of Euripides

• Agathon, an extraordinarily beautiful and effeminate Athenian tragedian

• Cleisthenes, a notorious homosexual

• A servant of Agathon

• An Athenian magistrate

• A Scythian archer, Athenian equivalent of a modern policeman

• Mica, a woman at the festival

• Critylla, a myrtle vendor, another woman at the festival

• Chorus of Agathon

• Chorus of Athenian women

Setting

The first part of the play is set on a street outside Agathon's house; the second before the Temple of the goddess Demeter.

Summary of Women at the Thesmophoria

Prologue

In front of the house of the real-life tragedian Agathon, located in the vicinity of the Temple of the goddess Demeter, Euripides and an elder relative of his (ancient manuscripts identify him as Mnesilochus, his father-in-law) discuss the appearance of the other poet. Apparently, Mnesilochus has never seen Agathon and doesn’t know how he looks like; precisely because he does, Euripides needs him badly. After they knock on the door, Agathon’s servant appears and asks the two men to be quiet since his master is composing a new drama. However, his language is so bombastic and pretentious that Mnesilochus cannot resist to ridicule the servant. “Let him be, friend,” remarks Euripides, “and, quick, go and call Agathon to me.”

While they wait for the servant to pass the message to Agathon, Euripides clarifies to Mnesilochus why he needs the fellow-tragedian. “This day will decide whether it is all over with Euripides or not,” he says. “But how?” replies Mnesilochus. “Neither the tribunals nor the Senate are sitting, for it is the third day of the Thesmophoria.” “That is precisely what makes me tremble,” explicates Euripides further. Because he “mishandles them” in his tragedies, “the women have plotted [his] ruin, and today they are to gather in the Temple of Demeter to execute their decision.” And that’s where Agathon comes in: Euripides plans to beg him to go to the Thesmophoria, mingle with the women, and, if necessary, stand up for him.

Soon enough, we realize why Agathon is the man for the job: he is brought before Euripides and his relative on a wheeled bed, softly reposing and clothed in a saffron tunic, and surrounded with feminine toilet articles. “If it is man we are waiting, then call me blind,” cries out Mnesilochus. “I see no man here, I only see Thessalian princess.” That is, of course, the point: thanks to his effeminate nature (the real-life Agathon was so lovely that his name became part of a phrase: “as beautiful as Agathon”), he should be able to easily infiltrate the Thesmophoria. However, Agathon seems more interested into singing a selection of his own highly lyrical tragedies, with the help of his servants who act as his chorus. Mnesilochus can’t bear it and, after mocking his verses, interrupts him: “Who are you?” he asks. “Do you pretend to be a man? Where is the cloak, the footgear that belong to that sex? Are you a woman? Then where are your breasts? Answer me. But you keep silent. Oh! Just as you choose; your songs display your character quite sufficiently.”

Agathon reads praise beneath the criticism: “Old man, old man,” he says, “I hear the shafts of jealousy whistling by my ears, but they do not hit me. My dress is in harmony with my thoughts. A poet must adopt the nature of his characters. Thus, if he is placing women on the stage, he must contract all their habits in his own person… If the heroes are men, everything in him will be manly. What we don't possess by nature, we must acquire by imitation.”

This back-and-forth between Agathon and Mnesilochus goes on for a bit more, when finally, Euripides interjects by noting that he is there for a matter much more serious than poetry. After he explains his fellow-tragedian the matter in question, Agathon justly asks why should he be the one to infiltrate the festival and not Euripides. “First of all, I am known,” replies Euripides, somewhat tongue-in-cheek. “Further, I have white hair and a long beard; whereas you, you are good-looking, charming, and are close-shaven; you are fair, delicate, and have a woman's voice.”

Agathon is not convinced and politely and firmly refuses Euripides’ request. Quoting lines from Euripides’ very plays, he claims that it’s up to every man to submit to his fate: “one must not try to trick misfortune,” he says, “but resign oneself to it with good grace.” Euripides, however, would prefer not to, and when Mnesilochus volunteers to lend him a hand, he immediately sets about disguising him as a woman. He shaves his beard and sings his loins, and then dresses him in a complete set of feminine attires: just like the razor and the wax, these are generously donated by Agathon as well. “But this is not I, it is Cleisthenes!” shrieks in horror Mnesilochus, comparing himself to Athens’ most disreputable homosexual. “True,” says Euripides, “you look for all the world like a woman. But when you talk, take good care to give your voice a woman's tone.” Making every effort in this direction, Mnesilochus departs for the women’s meeting at the Thesmophoria, where the women have already assembled, forming the Chorus.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The ruse succeeds: the women accept the disguised Mnesilochus as one of them, and, after a few prayers addressed to several gods and (especially) goddesses, immediately open the debate on Euripides. “If there be a man who is plotting against the womenfolk or who, to injure them, is proposing peace to Euripides and the Persians,” announces the leader of the Chorus, acting as herald in this environment, “pray the gods that they will overwhelm them with their wrath, both them and their families, and that they may reserve all their favors for you.”

Episodes

At this point, a woman named Mica separates from the group and asks to be given the floor. After her wish is granted, she proceeds to explain her main grievance with Euripides. Namely, that by styling women as “adulterous, lecherous, bibulous, treacherous, and garrulous,” he has made their husbands more watchful and now women can neither hide lovers nor steal something from the household stores in their husbands’ absence without them noticing afterward. “Never have I listened to a cleverer or more eloquent woman,” replies the Chorus. “Everything she says is true; she has examined the matter from all sides and has weighed up every detail. Her arguments are close, varied, and happily chosen.”

Now, a second woman, a myrtle vendor by the name of Critylla joins the discussion. Her problem with Euripides is not really gender-related, but financial and spiritual. She explains to the Chorus that her husband died some time ago in Cyprus, leaving her with five children. Even so, up until recently, she did manage to make ends meet by weaving religious chaplets and selling them at the myrtle market. However, the value of her business has decreased by half since Euripides started producing plays and persuading Athenians through his tragedies that there are no gods. “This is even more animated and more trenchant than the first speech,” replies the Chorus. “All she has just said is full of good sense and to the point; it is clever, clear and well calculated to convince. Yes! we must have striking vengeance on the insults of Euripides!”

At this point, Mnesilochus sees no alternative but to speak up, and makes an eloquent, but very misguided defense of the dramatist. His main argument: the women should, in fact, be grateful to Euripides for he has revealed only a small part of their sins. As evidence, he recites in detail his own make-believe sins as a married woman, and causes an uproar in the assembly. As the women are about to chastise Mnesilochus (or, rather, the woman they believe he is), a female messenger is seen approaching in hot haste.

The female messenger turns out to be of the opposite sex: it is the already-mentioned Cleisthenes, a homosexual so effeminate that he is described as the only man in Athens allowed to female gatherings. He doesn’t waste time before blurting out the following words to the leader of the Chorus: “They say that Euripides has sent an old man here to-day, one of his relations... so that he may hear your speeches and inform him of your deliberations and intentions.” So, this means even worse news for Mnesilochus who now becomes the target of a thorough investigation. The women eventually remove his clothes and his sex is revealed before everybody. As Cleisthenes departs to report Mnesilochus to the magistrates, Mnesilochus tries finding a way to escape. Desperate times call for desperate measures, so he tears Mica’s baby from her breasts and threatens to kill it unless he is released. The scene comes from Euripides’ play Telephus and is parodied in The Acharnians. And just like in The Acharnians, Mica’s baby turns out to be an object: in this case, wineskin. Even so, it is very dear to a drinker such as Mica, and she can’t help but cry when Mnesilochus tears open the wineskin with a knife. In tears, Mica catches its precious blood in a cup. “Out upon you, you pitiless monster!” she cries out.

Since this strategy advances Mnesilochus fortunes not one bit, he devises another plan. Remembering Euripides’ lost play Palamedes, he sends a few messages to his relative Euripides via a few oar-blades. As far as we know, in Palamedes – after the death of the eponymous protagonist – his brother Oeax wrote the news of it on a number of oar-blades which he subsequently cast into the sea, hoping that one of them will eventually be washed over to the shore by the waves and thus reach their father Nauplius with the truth. In Women at the Thesmophoria, Mnesilochus uses the same oar-blades (they were theatrical props at the same theater a few years before) and expects them to reach Euripides – even though there’s only dry ground surrounding him. Hoping for a favorable wind, Mnesilochus retreats to wait for Euripides.

Parabasis

Left alone, the Chorus of women delivers something resembling a parabasis, in which the virtues of women and men are compared, to the advantage (of course) of the former. Similarly as in Peace, the parabasis seems hastily composed and/or incomplete.

Episodes

As ingenious as it might have initially seemed, Mnesilochus’ attempt to contact Euripides by enacting a maneuver from one of his plays proves unsuccessful. However, this doesn’t discourage him from employing a similar tactic: he now starts reciting lines from the part of Helen in Euripides’ same-titled play, performed just a year before at the same festival as Women at the Thesmophoria. Amazingly (just as in Helen), Euripides (disguised as Menelaus) appears at the very same place that Mnesilochus/Helen is held captive. One problem solved, but the other one is far more difficult: how to carry Mnesilochus away from the temple of Demeter. This problem becomes even more complicated as the magistrate to whom Cleisthenes has reported Mnesilochus arrives. He chases Euripides/Menelaus away and imprisons Mnesilochus. At his orders, a Scythian policeman binds Euripides’ relative to a plank with the intent of making him a ridiculous spectacle to the world in his feminine attire.

Euripides, though, has already promised to never abandon him – at least not before trying as many of his “numberless artifices” as possible. So, Mnesilochus turns to another play of his relative for personal salvation. The ploys from Palamedes and Helen may have proved ineffective, but quoting a lament by Andromeda may result in a different outcome. In reality, the only thing it results is an absurd scene in which Euripides appears above him disguised as Echo and merely repeats the final word of everything Mnesilochus and his Scythian guardian say.

The fourth and final play enacted by the pair is Perseus: Euripides appears as its protagonist and attempts to rescue the damsel in distress – that is Mnesilochus. However, the Scythian isn’t fooled and to Euripides’ “I will break her bonds” replies with “And I will cut off your head.” “Ah! what can be done?” – Euripides quotes himself as he is departing from the stage. “What arguments can I use? This savage will understand nothing! The newest and most cunning fancies are a dead letter to the ignorant. Let us invent some artifice to fit in with his coarse nature.”

Exodos (Exit Song)

True to his words, Euripides now appears thinly disguised as an old procuress, carrying a harp and followed by a dancing girl and a young flute-girl. The mask is so bad that the Chorus immediately recognizes him. But Euripides reveals that the mask was never intended for the women. “Women, if you will be reconciled with me, I am willing, and I undertake never to say anything ill of you in future. This unfortunate man, who is chained to the post, is my father-in-law; if you will restore him to me, you will have no more cause to complain of me.”

The Chorus agrees to the terms of the peace proposal, and allows Euripides to freely approach the Scythian who is so captivated with the girls that he neither recognizes the tragedian nor suspects something dodgy. The girls lure him for a few seconds away from Mnesilochus and Euripides manages to release him and take him home. Realizing the trick, the policeman starts chasing the two, but the Chorus sends the distressed Scythian off in the opposite direction. “Go your way and a pleasant journey to you!” the leader of the Chorus says as he departs. Then she turns to the audience and announces the end of the play in a vein similar to Shakespeare’s Bottom: “But our sports have lasted long enough; it is time for each of us to be off home; and may the two goddesses reward us for our labors!”

A Brief Analysis

Mary Kay-Gamel – professor of classics, comparative literature, and theater arts at the university of California – considers Women at the Thesmophoria “Aristophanes’ funniest play.” Similarly, Eugene O’Neill Jr. calls it “perhaps the best comedy” produced by its author. Even more tellingly, Ian Storey and Arlene Allan describe it as “arguably one of the wittiest of Western comedies.” The reason why it is not as famous as Lysistrata, The Birds or The Frogs is twofold: 1) “because literary parody is less appealing than out-and-out political satire” and 2) because all but one of Euripides’ plays parodied by Aristophanes are now lost.

The surviving play is Helen and, by comparing its text to the relevant scene from this comedy, “we can examine directly how Aristophanic parody operated.” (Storey and Allan). The comparison makes somewhat evident why Aristophanes was so fond of parodying Euripides (rather than, say, Sophocles). As Alan Sommerstein writes, “Euripides had less than Sophocles of ‘the art that conceals art’: his techniques were more transparent, his mannerisms of structure, language and presentation more predictable, his interest in current speculations in physics and ethics more obvious, and his inclination to indulge a taste for argumentative ingenuity for its own sake, sometimes to the detriment of dramatic cohesion, led to his acquiring the name of a ‘composer of little phrases from the lawcourts.’”

Moreover, “Euripides had also acquired the reputation of being fond of portraying wicked women”: in his 17 surviving tragedies, there are 7 women who, within the action of the play, commit, attempt, or plot murder (Medea, Phaedra, Hermione, Hecuba, Electra, Creusa and Agave). It’s interesting to note that almost all of Euripides’ plays parodied in Women at the Thesmophoria were quite recent in 411 BC: Helen was performed just a year before, as was Andromeda, and Palamedes was probably first performed in 415 BC. First produced thirty-seven years before Women at the Thesmophoria, Telephus is the only exception, but it was clearly a tragedy that stuck both in Aristophanes’ and the audience’s memory, for the comedian parodied it in The Acharnians as well.

In addition to these “extended scenes of paratragedy,” Women at the Thesmophoria is famous also for being almost apolitical and for being one of Aristophanes’ three “gender plays” (together with Lysistrata and Assemblywomen). Practically all male characters in the play dress as a woman at some point, and gender is confused throughout. However, unlike the women in Lysistrata and Assemblywomen – “no woman in this comedy gives an indication of wanting to take over male roles in politics or elsewhere… So far as the characters are concerned, the gender-inversion is all one way: in this play (almost) everyone is a woman” (Sommerstein).

Sources

There are a few translations of Women at the Thesmophoria available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read an anonymous translation for the Athenian Society edited by Eugene O'Neill, Jr. here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Benjamin B. Rogers loose verse adaptation here.

See Also: Aristophanes, Euripides, The Acharnians, Helen

Women at the Thesmophoria Video

Women at the Thesmophoria Associations

Link/Cite Women at the Thesmophoria Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Women at the Thesmophoria ". GreekMythology.com Website, 03 Sep. 2020, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Aristophanes/Women_at_the_Thesmophoria_/women_at_the_thesmophoria_.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.