Trojan War

One of the most well-known tales ever narrated (most notably in Homer’s “Iliad”), the Trojan War is undoubtedly the greatest war in classical mythology. Waged by an Achaean alliance against the city of Troy, the war originated from a quarrel between three goddesses (Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite) over a golden apple, thrown by the goddess of strife at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, and inscribed with the words “for the fairest.” Unwilling to settle the dispute himself, Zeus sent the goddesses to Paris, the young prince of Troy, who gifted the apple to Aphrodite for the goddess had promised him, as a token of gratitude, the love of Helen, the most beautiful girl in the world. Aphrodite fulfilled her promise and, before too long, Helen eloped with Paris from her royal court in Sparta to the Trojan palace. Helen’s husband, Menelaus – incited by his even more powerful brother, Agamemnon – assembled a large army of Achaean leaders, most of them obliged to protect the sanctity of his marriage by a previous oath. After the diplomatic attempts to settle the dispute early on yielded no result, the Greek forces surrounded the city of Troy and held it under siege for a decade. In the tenth year of the war, after the fighting had already taken the lives of some of the greatest heroes on either side (Achilles, Ajax, Patroclus, Protesilaus; Hector, Sarpedon, Memnon, Cycnus), Odysseus devised the ruse of the Trojan Horse, which finally brought the downfall of Troy. The Achaeans raided the city and set it afire, slaughtering scores of innocent people and desecrating too many hallowed grounds to escape the subsequent wrath of the gods. As a result, few of them managed to return safely to their homes; and those who did may have been the less fortunate ones.

The Background of the War

Peleus and Thetis

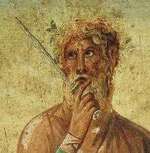

The genesis of the Trojan War goes all the way back to a divine love contest, and a prophecy concerning the very foundations of the Olympian order. Namely, decades before its commencement, both Zeus and Poseidon fell in love with a beautiful sea-nymph named Thetis. Each of them wanted to make her his bride, but both backed away once they were told (whether by Themis or Prometheus) the dire consequences of such an action; for “it was fated that the sea-goddess should bear a princely son, stronger than his father, who would wield another weapon in his hand more powerful than the thunderbolt or the irresistible trident, if she lay with Zeus or one of his brothers.” So as not to risk anything, Zeus decided to give Thetis’ hand in marriage to King Peleus, “the most pious man living on the plain of Iolcus.”

The Apple of Discord

Now that the husband was determined, Zeus organized a grand feast in celebration of Peleus' and Thetis' marriage, at which all the other gods were invited, except for the disagreeable goddess of strife, Eris. Annoyed at being stopped at the door by Hermes, before leaving the gathering, she threw her gift amidst the guests; it was the Apple of Discord, a golden apple upon which the words "for the fairest" had been inscribed. Before long, Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite started quarreling over who should be the one to take the apple, and, not being able to decide on their own, demanded from Zeus to settle the dispute.

The Judgment of Paris

Zeus knew that any choice meant inciting the anger of at least two goddesses, so he wisely decided to abstain from judgment; instead, he appointed Paris, the young prince of Troy, to be the judge. Paris was tending his flocks on Mount Ida when the three goddesses approached him. However, he was unable to make a choice even after seeing each of the three goddesses naked. So, unsurprisingly, it was time for some bribing. First, Hera gave her word to Paris that, in gratitude for choosing her, she would grant him both political power and the throne of the continent of Asia; then, Athena offered him wisdom and excellent skills in battle; finally, Aphrodite promised Paris the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta. There could be only one outcome: without batting an eyelash, Paris awarded the apple to Aphrodite, and, disregarding the prophecies of his brother and sister, Helenus and Cassandra, set off for Sparta to claim his reward.

The Suitors of Helen and the Oath of Tyndareus

Now, Aphrodite wasn’t the only one who knew that Helen, the stepdaughter of King Tyndareus of Sparta, was the most beautiful woman in the world; not by a long shot: in fact, Tyndareus’ court was filled with numerous noble suitors ever since her availability for marriage had been announced months before the Judgement of Paris. However, much like Zeus in the case of the Apple of Discord, Tyndareus was unwilling to create himself political enemies, so he stalled the decision on the bridegroom. The wisest – and least enthusiastic – of the suitors, Odysseus of Ithaca, offered the King an escape plan, asking in return for the hand of Penelope, Tyndareus’ niece; the King agreed, and Odysseus advised him to make all of Helen’s suitors swear an oath that they would protect the couple regardless of the final decision. After the oath had been taken, Tyndareus picked Menelaus to be his daughter's husband, effectively making him the successor of the Spartan throne through Helen.

The Abduction of Helen

Unfortunately for Menelaus, some time after his marriage with Helen had been officialized, his uncle Catreus, the King of Crete, was mistakenly killed by one of his sons. While Menelaus was away there at his funeral, Aphrodite used the opportunity to disguise Paris as a diplomatic emissary and successfully smuggle him inside the palace of the Spartan royal family. Owing to the goddess’ influence and one of Eros’ unmistakable arrows, Helen welcomed Paris much too warmly, and, after a night of passion and promises, agreed to elope with him to Troy.

Recruiting the Greek Heroes

Menelaus returned home and, before too long, realized that his wife had left him – and left him for a lesser man. He wasted no time: incited by his much more powerful brother, Agamemnon, he invoked the Oath of Tyndareus and called upon the help of all Achaean leaders who had previously sought with him the hand of Helen. And they all came, each the head of a mighty army: Ajax and Teucer of Salamis, sons of Telamon; Ajax of Locris, son of Oileus, and Idomeneus of Crete, son of Deucalion; Diomedes of Argos, son of Tydeus, and Elephenor of Euboea, son of Chalcodon; Philoctetes of Meliboea, son of Poeas, and Protiselaus of Philace, son of Iphicles; and many, many more: in fact, as many as forty-five great Achaean leaders and warriors. There was nowhere any sign of Odysseus, though.

Recruiting Odysseus

And for a good reason: by this time, Odysseus was a happily married father of a one-year-old boy named Telemachus, and he had learned from the seer Halitherses that if he took part in the Trojan expedition, it would take him many years to return home. So, when the envoy in charge for his recruitment arrived at his palace in Ithaca, he pretended to be mad by harnessing a donkey and an ox to a plow and sowing salt instead of grain in his fields. However, Palamedes saw through the ruse and put Telemachus in front of the plow. Odysseus had no option but to change course and, thus, he revealed both his plan and his sanity. Accepting his fate – and knowing from the seer Calchas that his presence was a prerequisite for Greek victory – Odysseus almost immediately set on a mission to find and enlist the man fated to become the greatest of all Greek heroes under Troy: Achilles.

Achilles: A Flashback

Achilles was none other than the child Zeus and Poseidon never wanted to have: the only surviving son of Peleus and Thetis. Even before his birth, his mother knew that Achilles was destined to either lead an uneventful but long life or a glorious one that would end with him dying young on the battlefield. Fearing for her son's future wellbeing, Thetis decided to grant him immortality. While he was still an infant, she took him to the River Styx – one of the rivers that ran through the Underworld – and dipped him in the waters, thus making him invulnerable. However, Thetis did not realize that the heel of the boy, by which she had held him, did not touch the waters of the Styx; this would later turn out to be the cause for Achilles’ downfall, and is the origin of the modern-day phrase "Achilles' heel," signifying a vulnerable spot despite overall strength. Anyway, after she had completed the ritual – so as to be even safer – Thetis disguised Achilles as a girl and hid him among the maidens at the court of King Lycomedes of Skyros.

Recruiting Achilles

Soon after joining the Trojan expedition, Odysseus learned of Achilles’ whereabouts; so, he teamed up with Telamonian Ajax and Phoenix, an old tutor of Achilles, and the three went to Skyros to recruit the hero. There, they either blew a war horn, on the sound of which Achilles was the only woman that took a spear in hand, or they appeared as merchants selling jewels and weapons, and Achilles was the only woman interested in the latter. Either way, now the Achaean forces were complete; and ready to attack Troy.

Reaching Troy

An Early Sign

The Achaean leaders first gathered at the port of Aulis. A sacrifice was made to Apollo, and the god sent an omen: a snake appeared from the altar and slithered to a bird's nest, where it ate the mother and her nine babies before it was turned to stone. The seer Calchas interpreted the meaning of the event for everybody: Troy was to eventually fall – but not before the tenth year of the war!

Telephus

There was no time for losing: the Achaeans immediately set sail for Troy, even though no one knew the exact way. So, by mistake, they landed too far to the south, in the land of Mysia, ruled by King Telephus. The battle which ensued took the life of many a great Greek warrior, all the while highlighting Achilles’ superhuman strength: in addition to killing numerous Mysians, Achilles (who was barely fifteen at the time!) managed to also wound their king Telephus, a son of Heracles. And as Telephus found out from an oracle soon after the Achaean ships left Mysia, this wound was so unique that it could only be cured by the one who had caused it. Eight years did Telephus search for Achilles, and, eventually, he found him in Aulis, where the Achaean leaders had gathered once again for a consultation, despairing over their incapability of reaching Troy. Now, Achilles had no medical knowledge whatsoever, so he was quite surprised when Telephus approached him with his request. Always shrewder than everybody, Odysseus realized that the prophecy might not refer to the man – but to the weapon which had inflicted the wound; heeding his advice, Achilles scraped off the rust of his Pelian spear over Telephus’ wound, and, just like that, it stopped bleeding. Out of gratitude, Telephus agreed to tell the Greeks the route to Troy.

Iphigenia at Aulis

However, the Greeks now faced an even bigger problem: even though they finally knew the way to Troy, they were unable to set sail from Aulis because, for most of the time, there was no wind of any kind, let alone favorable one. The seer Calchas realized that this must be some kind of retribution from the goddess Artemis, furious at Agamemnon for killing one of her sacred deer. Artemis’ demand for appeasement was an unspeakably cruel one: the sacrifice of Agamemnon's virgin daughter, Iphigenia. After some deliberation, Odysseus lured Iphigenia to Aulis on the pretext of marriage with Achilles. After finding out that he had been used in such a vicious ruse, Achilles tried to save Iphigenia’s life, only to learn that all of the other Greek commanders and soldiers are in support of the sacrifice. Bereaved of options, Iphigenia gracefully accepted her fate and placed herself on the altar. Some say that, unfortunately, that was the end of her; others, however, claim that just as Calchas was about to sacrifice her, Artemis substituted Iphigenia for a deer and took her to Tauris where she became the goddess' high priestess.

Tenedos

Either way, the winds picked up again after the sacrifice and the Achaean fleet was finally able to set sail toward Troy. While on the way there, they stormed the island of Tenedos; unaware of his identity, Achilles killed the island’s king, Tenes, who happened to be a son of the god Apollo. It was a fateful decision since Thetis had warned him not to kill any sons of Apollo, lest he wants to be killed by the god himself; just as forewarned, many years later, Apollo will get his revenge.

The Course of the War

The Diplomatic Mission

From Tenedos, the Greeks sent a diplomatic mission to Troy – probably consisting solely of Menelaus and Odysseus, though some say entailing Acamas and Diomedes as well – whose mission was to recover Helen by peaceful means. The Trojans not only refused this, but they also threatened to kill the envoy and only the intervention of the Trojan elder Antenor saved the lives of Menelaus and Odysseus. The message was loud and clear: if they wanted Helen back, the Greeks would have to come and get her through the use of arms.

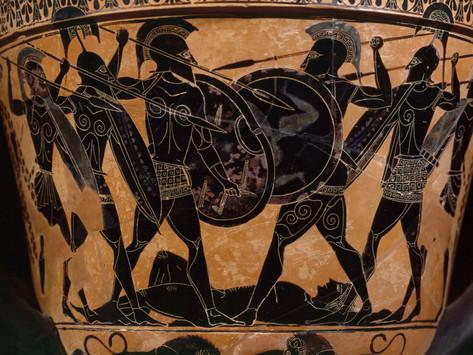

Protesilaus

And so they did: after many years of wandering, the Greek fleet sailed the short route from Tenedos to Troas and finally arrived at the desired destination. However, everybody was now reluctant to land, as an oracle had once prophesized that the first Greek to step on Trojan soil would be the first one to die in the war. Some say that Protesilaus took the initiative willingly and sacrificed himself for the sake of Greece, but others claim that he was tricked by Odysseus who announced that he would disembark first, but, circumvented the prophecy by stepping on his shield once ashore. Either way, it was Protesilaus who had the misfortune of being the first victim of the Trojan War, dying during a face-to-face duel with Troy’s most celebrated hero, its beloved prince, Hector.

The Nine-Year Siege of Troy

The siege of Troy lasted for nine years, but the Trojans – able to maintain trade links with other Asian cities, in addition to getting constant reinforcements – firmly held their ground. Near the end of the ninth year, the exhausted Achaean army mutinied and demanded to return home; Achilles, however, boosted their morale and convinced them to stay a bit longer.

The Rage of Achilles

On the tenth year, Chryses, a Trojan priest of Apollo, visited Agamemnon and asked for his daughter Chryseis' return. Agamemnon, who had taken her as war booty and kept her to be his concubine, refused to give Chryseis back. So, Chryses prayed to Apollo for some kind of a divine payback, and Apollo inflicted the Greek army with а plague. Pressed by his armies, Agamemnon had no option but to return Chryseis to her father; however, so as to salvage his ego and reputation, he took Achilles' concubine Briseis as his own. Achilles, infuriated, retired to his hut and announced that he had no intention of fighting any longer – at least not as long as Agamemnon was in charge.

Patroclus

Now that Achilles was out of the action, the Trojans started winning battle after a battle, eventually driving the Greeks back to their ships and almost setting the ships on fire. Patroclus, Achilles’ closest friend, couldn’t take this any longer; so, he asked Achilles for his armor and, disguised as him, took command of the Myrmidon army. Their morale boosted, the Achaeans successfully repelled the Trojan attack; ever the fearless warrior and never shying away from a duel, Hector barely spared a moment before he ran in the direction of the man everyone thought was Achilles; in the fight which followed, Hector managed to kill his opponent – only to realize that it had been Patroclus all along.

The Victorious Return of Achilles

Achilles, maddened with grief, swore vengeance; with him back on the battlefield, the war took an entirely different course. After slaying a vast number of Trojans, Achilles eventually got the fight he wanted: Hector himself. Even though this duel paired off the best fighters of both armies, everyone was well aware that there could be only one victor from it; in fact, even before its commencement, fully aware of his opponent’s demigod status, Hector had said goodbye to his wife Andromache and his little boy Astyanax. After killing Hector, Achilles refused to surrender his body to the Trojans for burial, and instead, he desecrated it by dragging it with his chariot in front of the city walls. He eventually agreed to return it, after he was moved to tears by the visit of King Priam of Troy, who had come alone to the Greek camp to plead for the body of his son with his son’s murderer.

The Death of Achilles

Achilles didn’t live too long after these events: an arrow shot by Paris and guided by Apollo hit him on his heel as he was trying to enter Troy. He was later burned on a funeral pyre, and his bones were mixed with those of his close friend Patroclus. Paris himself was subsequently killed by an arrow, fired by Philoctetes, straight from the legendary bow of Heracles.

Odysseus’ Ploy: the Trojan Horse

Numerous other heroes died in the following days. Finally, Odysseus devised a plan to end the war for good. He asked that a wooden horse with a hollow belly be built. Soldiers hid in the interior of the horse, which was then wheeled in front of Troy’s city gates. Meanwhile, the Greek fleet sailed away to the nearby island of Tenedos, leaving behind a double agent named Sinon. After some deliberation, Sinon convinced the Trojans that the Greeks had withdrawn and that the Trojan Horse was a divine gift that should bring much good fortune to Troy. Even though Apollo’s priest Laocoon and the prophetess Cassandra had warned them not to, the Trojans refused to listen and brought the horse into the city. They then started feasting and celebrating the victory. However, during the night, the Greek ships sailed back, and the soldiers hidden inside the horse jumped out of it and opened the gates. A massacre followed and, eventually, after a decade-long war, Troy fell.

The Raid of Troy

The Greeks raided the city and set much of it on fire, destroying temples and sacred grounds and committing offense after offense against the Olympian gods. King Priam was brutally murdered by Achilles’ son Neoptolemus, and Queen Hecuba was either enslaved by Odysseus or went mad upon seeing the corpses of many of her children. One of her daughters, Polyxena, was sacrificed on Achilles’ grave, and another, Cassandra, was dragged away from Athena’s temple by the Locrian Ajax and assaulted in an act so vile that the statue of the goddess turned its eyes away in horror. In possibly the cruelest deed of them all, either Neoptolemus or Odysseus threw Hector’s little son, Astyanax, from the walls of Troy and to his death. One of the few heroes who escaped the carnage alive was Aeneas, who subsequently reached Italy and founded the first Roman dynasty.

The Aftermath

The gods never forget and rarely forgive. The surviving Greek heroes will learn this the hard way: although victorious, most of them will be severely punished for their transgressions. In fact, only few will ever reach their homes – and only after numerous exploits and adventures. Even fewer will be greeted with a warm welcome, either ending up being exiled into oblivion or finding their deaths at the hands of their loved ones. Or, in some cases, both.

Trojan War Sources

Even though Homer’s “Iliad” describes just a short period of about fifty days during the tenth year of the Trojan War (with the bulk of it focusing on no more than five), it is, unquestionably, the most well-known primary source for the conflict. The epic ends with the burial of Hector’s body, and to learn what happened next (including the famous Trojan Horse ploy), you must consult the second book of Virgil’s “Aeneid.” Most of the epitome of Apollodorus’ “Library” narrates the events of the Trojan War – from its mythological background through a summary of the “Iliad” and the lost epic “The Sack of Troy” and all the way to the ill-fated returns of the heroes to Greece.

See Also: Achaeans, Thetis, Peleus, Paris, Helen, Achilles, Tyndareus, Menelaus, Odysseus, Calchas, Clytemnestra, Agamemnon, Iphigenia, Patroclus, Hector, Priam, The Trojan Horse, The Sack of Troy

Trojan War Video

Link/Cite Trojan War Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Trojan War". GreekMythology.com Website, 14 Nov. 2018, https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/The_Myths/Trojan_War/trojan_war.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.